The Nashville restaurant City House interprets Italy like a lost Southern state, tucked somewhere between Tennessee and Emilia-Romagna. The highlights of my first meal there, not long after the restaurant opened in late 2007, were a potato frico that looked and tasted like it was flattop-fried by a moonlighting Waffle House breakfast cook; a catfish fillet topped with a relish of garlic, chiles, mint, and orange; and a wood-fired pizza, layered with house-cured salami and rounds of pineapple, seemingly inspired by a night on the couch with a spliff.

I didn’t know it then, but I had glimpsed the emergence of a genre. Chef Hugh Acheson, who made his rep at Five & Ten in Athens, Georgia, was the first to clue me in. We were talking about the Florence, the new restaurant he will open this year in Savannah, when Acheson told me that he hopes to pull off “something like what Tandy does in Nashville.” He said it casually. And I agreed quickly. But until that moment, I hadn’t thought of City House chef Tandy Wilson as a creator of his own gastronomic nation-state. Reading through my sauce-splattered notes from that first dinner, in which provincial Italy and the rock-and-roll South meshed seamlessly, I wondered what else I had missed.

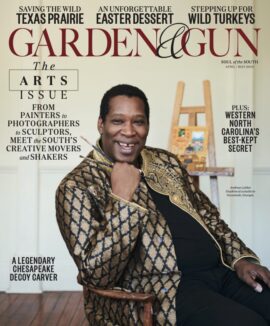

Photo: Andrea Behrends

Dinner Party

The pizza bar at City House.

After eating two City House meals in recent months, I can now tell you that I missed lots. Some of my oversights were cultural. Others were culinary. All reveal, in the bright light of today, a chef in his prime, digging deeper into his home, growing more comfortable with his place in the world. His colleagues affect a similar confidence. When I asked our waiter, Paul, about a blister-lipped pizza, troweled with cauliflower ragout, he said, “It’s kind of like a pretentious version of a Totino’s.” I liked him instantly. What he meant to communicate, I think, was that although City House aspires to be a great restaurant, and the chef has an honest pedigree, and the food is unimpeachably delicious, no one here suffers the sorts of diners who focus more on status than sustenance.

Wilson sets that tone. Get him talking and he speaks of serving his community in the manner of Arnold’s Country Kitchen, the Nashville meat-and-three bunker, famous among white-shoe attorneys and booted construction workers alike for horseradish-kissed greens and custardy banana pudding. A third-generation native in a city flush with new arrivals, Wilson projects a workingman’s vibe. Like a mid-twentieth-century grocery store clerk, sketched by Norman Rockwell, he tucks a pencil behind his ear. Instead of starched chef jackets, he wears rumpled T-shirts. Mesh-backed gimme caps, not pleated toques, cover his balding pate. His chosen backdrop—a brick home in the emerging Germantown neighborhood, decorated with a minimalist’s attention to detail and a maximalist’s love of pig figurines—reflects the same insouciant grittiness.

When Wilson steps onto the line, alongside Aaron Clemins, his sous-chef since day one, he cooks feed-the-people food, which is to say he braises hunks of pork, piles high nests of greens, and tosses loops of pasta with peas and beans. On the plate, his food is substantial. On the menu, appetizers hover at the nine- to-eleven-dollar mark, while pastas sell for around fifteen.

Photo: Andrea Behrends

Cauliflower salad with cracked wheat, citrus, and walnuts.

All that democracy does not come at the price of complexity or inventiveness. Order a dish of clams, tossed with white beans, and Wilson crowns the assemblage with bread crumbs, rendering the sort of crunch more often achieved by expert fry cooks. Fork into the gnocchi and you recognize an affirming textural depth, owing to Wilson’s unconventional use of buttermilk cornbread, not riced potatoes, as the basis for those dumplings. Choose the trout, stuffed with peanuts and raisins, and you taste an affinity for Sicily, where pine nuts and currants are similarly deployed. Let other chefs play ass-tag with the next vanguard vegetable. Wilson, instead, loves all over cauliflower, tossing florets with cracked wheat and pomegranates to make a stunning salad.

Acheson isn’t the only chef following his lead. Jacques Larson, executive chef at the Obstinate Daughter, the new Italian-homage restaurant near Charleston, South Carolina, told me that Wilson cooks pork like an Italian. He cited Wilson’s way with shanks, which he cooks in the style of osso buco. And he talked about Wilson’s obsession with ham curing. Based on recent meals at Rolf and Daughters—where Philip Krajeck works a broad Mediterranean palate, schooling a new generation of chefs on the possibilities of house-made pastas—it seems other Nashville chefs are also tacking similarly, crafting Italian-ish weeknight food for good eaters, not trophy food for Euro-poseurs. While just a few smart chefs have been watching, Tandy Wilson has redrawn the Southern map so that the culinary distance between Nashville and Bologna is comparable to the actual distance between Nashville and Murfreesboro.