Most of us visit museums to immerse ourselves in art. Jim Sokol and his wife, Lydia Cheney, just go home. The twenty-three-foot-high walls of the Alabamans’ Birmingham condo are crammed with paintings and textiles; sculptures crowd side tables and bookshelves. “There’s art everywhere,” Sokol says. “We don’t move it because we’re having a party. If there’s a piece on the dining room table and it gets barbecue sauce on it, then it gets wiped off.”

That’s an easygoing attitude for a collector. But Cheney and Sokol take a populist approach to fine art. They’re especially attracted to the work of Southern folk artists—art-world outsiders who often lack formal training but draw inspiration from both their faith and a connection to place. The couple own some sixty pieces of folk art. But as much as they enjoy the works themselves, it’s the human stories behind the art that interest them most. In fact, they rarely buy anything without meeting the artist first. “Knowing who makes it and why they’re making it,” Sokol says. “That drives everything Lydia and I buy.”

Photo: Jean Allsopp

Lydia Cheney and Jim Sokol surrounded by pierces from their collection.

The couple are big fans of Charlie Lucas of Pink Lily, Alabama, who began sculpting camels and other images after a back injury put him out of work. “He had forty acres of hardscrabble land where his extended family would build houses,” Sokol says. “He picked nails out of the railroad ties and trash that fell off the adjacent trains and made these amazing sculptures.” Lucas, who is also known as the Tin Man, couldn’t read when he got started, but he knew how to weld, which provided the technical foundation for his art.

“We say they are untrained or uneducated,” Sokol says, “but most of these artists learned how to do mechanics or weld from a parent or grandparent who did that for a living. There’s a lot of knowledge that came from a practicality of having to do things and work with things.” The couple’s most prized Lucas work is a painting of a red dog that Lucas gave to Cheney at a party she and Sokol hosted for him. But Sokol readily admits, “We might answer differently next week.”

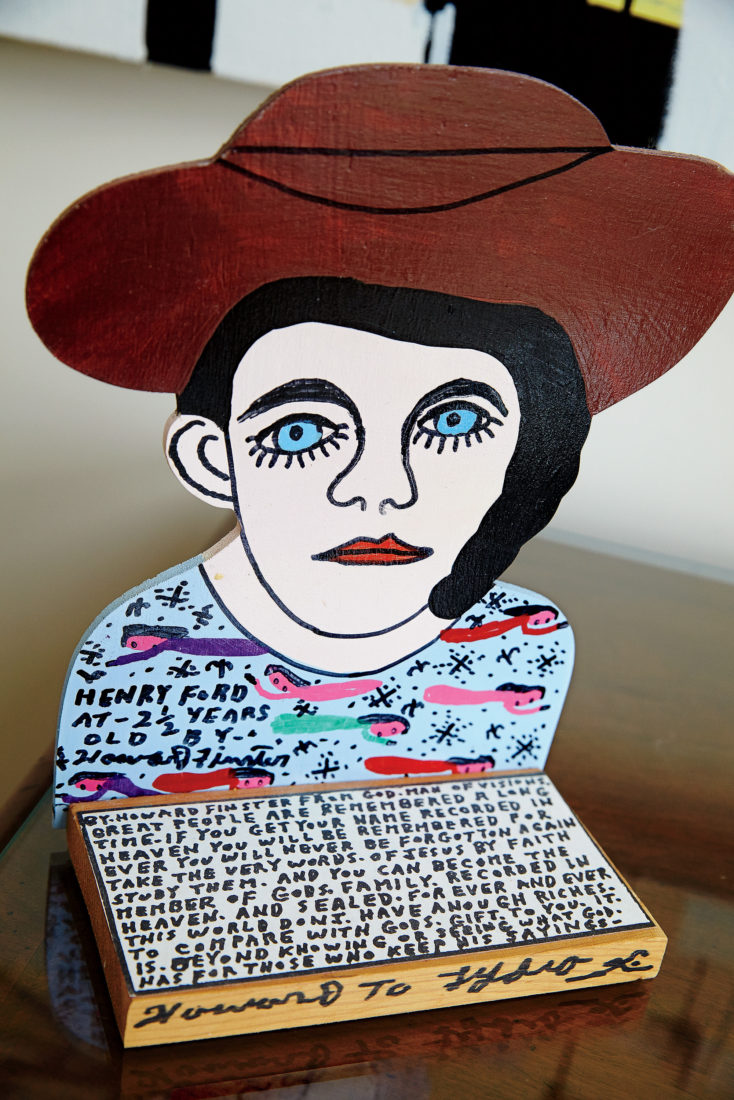

Photo: Jean Allsopp

A portrait of Henry Ford by legendary Georgia artist Howard Finster.

Sokol met Jimmy Lee Sudduth, a farmer known for painting with clay-and plant-based pigments, at Alabama’s Kentuck Festival of the Arts. Their collection includes a full-length self-portrait of the artist in overalls and a cap, accompanied by a snake. Sokol also befriended the quilter Nora Ezell and commissioned a multipaneled quilt called Beautiful Birmingham, which depicts the city’s landmarks.

Photo: Jean Allsopp

Paintings by Mose Tolliver.

Sokol and Cheney were already art collectors when they met on a blind date—at the Birmingham Museum of Art in 1991. But it was as a couple that their interest in folk art grew. Both are from Alabama, and they liked the idea of supporting local artists. They cite the civil rights movement and the inequity they witnessed as young people as major influences. “So many of the folk artists came out of that environment—out of the worst of it—and made art that was so meaningful,” Sokol says.

For Cheney, a black-and-white painting from the late Georgia preacher Howard Finster has special meaning. Titled Empty Road, it originally belonged to her late sister, Anne. The piece depicts dense blocks of religious texts and a road winding through a garden toward heaven. One of the world’s foremost folk artists, Finster is best known for illustrating the covers of both R.E.M.’s Reckoning album and Talking Heads’ Little Creatures, and for creating Paradise Garden in Summerville, Georgia, a labyrinth of adorned buildings, sculpture, found objects, and thousands of visionary paintings.

Photo: Jean Allsopp

Two Charlie Lucas camel sculptures.

Many of the pieces that Sokol and Cheney own are valuable today, but when they started buying folk art more than thirty years ago, it wasn’t on most collectors’ radar. They often paid $50 or $100 for a painting or sculpture. Sokol recalls sharing a beer with the Alabama artist Mose Tolliver while he painted, long before his work made it to the Smithsonian.

The couple are generous with their collection, often loaning pieces out to local venues and museums across the country. And they still regularly host artists at their home. While driving down their street, it’s not unusual to see a yellow school bus parked outside their condo, since they frequently invite civic groups and students for tours as well. “We are both so excited about what we have,” Cheney says, “that we love to share it with other people.”