When I finally worked up the nerve to talk to the handsome campus photographer at my college, he dropped this smooth-as-silk pickup line: “We should, uh, walk the dog together sometime.” I’m not sure what’s more telling: that this was his strategy, or that I fell for it without hesitation.

A few weeks later, when Dane swung open the door of his apartment to greet me, my gaze immediately fell to the weird-looking mutt eyeing me from between Dane’s feet. The dog’s ears were one size too big, moved independently of one another, and appeared to be controlled from above by invisible puppet strings. His awkward build was simultaneously leggy and runty. Jerry looked more like a child’s clumsy drawing of a dog than a flesh-and-blood Canis familiaris. I loved him instantly. Package deal, I thought as I crossed the threshold.

Jerry has no pedigree, nor does he resemble anything recognized by the American Kennel Club. As a college boy, Dane scooped him up as a puppy from the pound in Savannah, thinking he’d scored himself a yellow Lab on the cheap. What he wound up with looks more like a jackal. In fact, Jerry’s likely cousin is the Carolina dog, a breed of wild (and possibly native) dog that runs freely among the Southeastern pinewoods and wetlands. It’s the closest thing our country has to an honest-to-God dingo. A swamp dingo.

If there were a purebred designation for Jerry’s kind, its breed qualities would include the following characteristics: a body with twice as much skin as its skeleton needs, with curtains of neck fat that can be splayed wide like a spatchcocked chicken. An extensive nonverbal vocabulary, including one deep, guttural groan of discontent that sounds exactly like a heavy wooden door creaking open into a haunted castle. A pelt that sheds gauzy tumbleweeds of hair, which tend to drift across hardwood floors and congregate around air vents, especially when houseguests are present. An utterly debilitating phobia of golf carts. (No, we don’t know why.)

Jerry’s smart, but not in the way that purebred hunting or herding dogs are. More Artful Dodger than scholar, he’s clever enough to jangle his water bowl around to tell you he’s thirsty—fill ’er up, lady—but he won’t debase himself with frippery like “come” or “leave it” or “for the love of God, Jerry, please don’t eat that rat carcass.” (Gulp.) He’ll chase a tennis ball with abandon, but his human handlers can only achieve the “retrieve” part of fetch via an elaborate series of Wile E. Coyote–style traps, stunts, and decoys. What do you think I am, some kind of sucker? he seems to say.

During the nervous, fumbling days of my early courtship with Dane, Jerry was omnipresent. And that’s where he stayed. Thrusting a slobbery old ball into my lap on the couch while Dane and I got to know each other, and Know Each Other, over cheap merlot. Lurking in the dark as we stumbled drunkenly into the apartment after too many martinis, waiting for his nightly bathroom trip outside. One time during a good, long kiss on the couch, Dane and I paused to look up. There stood Jerry about ten inches away, quietly looming like some kind of bargain-basement gargoyle. He looked me straight in the eye, and winked.

Dane and I fell into an easy kind of love that fall, building our own vernacular of shared histories and inside jokes, all with this mutt tethered between us. “My boyfriend’s dog” became “our dog,” and Jerry soon greeted me with the same level of theatrics he had reserved for Dane. Together the three of us hiked and camped and embarked on road trips zigzagging thousands of miles around the country, always with Jerry in the backseat, proudly sporting the tattered red bandanna we called his “adventure cloth.”

On outings like these, I frequently joked that Jerry was exactly the kind of unassuming plebe who would unwittingly stumble upon a rare dinosaur fossil or a cache of buried treasure and make us—two art-school grads mostly subsisting on a diet of rice and legumes—rich. In fact, the closest he’d ever gotten to finding “treasure” was at a campsite in the Adirondacks: We unzipped the tent in the morning and Jerry took off, only to emerge from the brush ten minutes later with a face smeared in charcoal ash and someone’s hamburger dangling from his jowls.

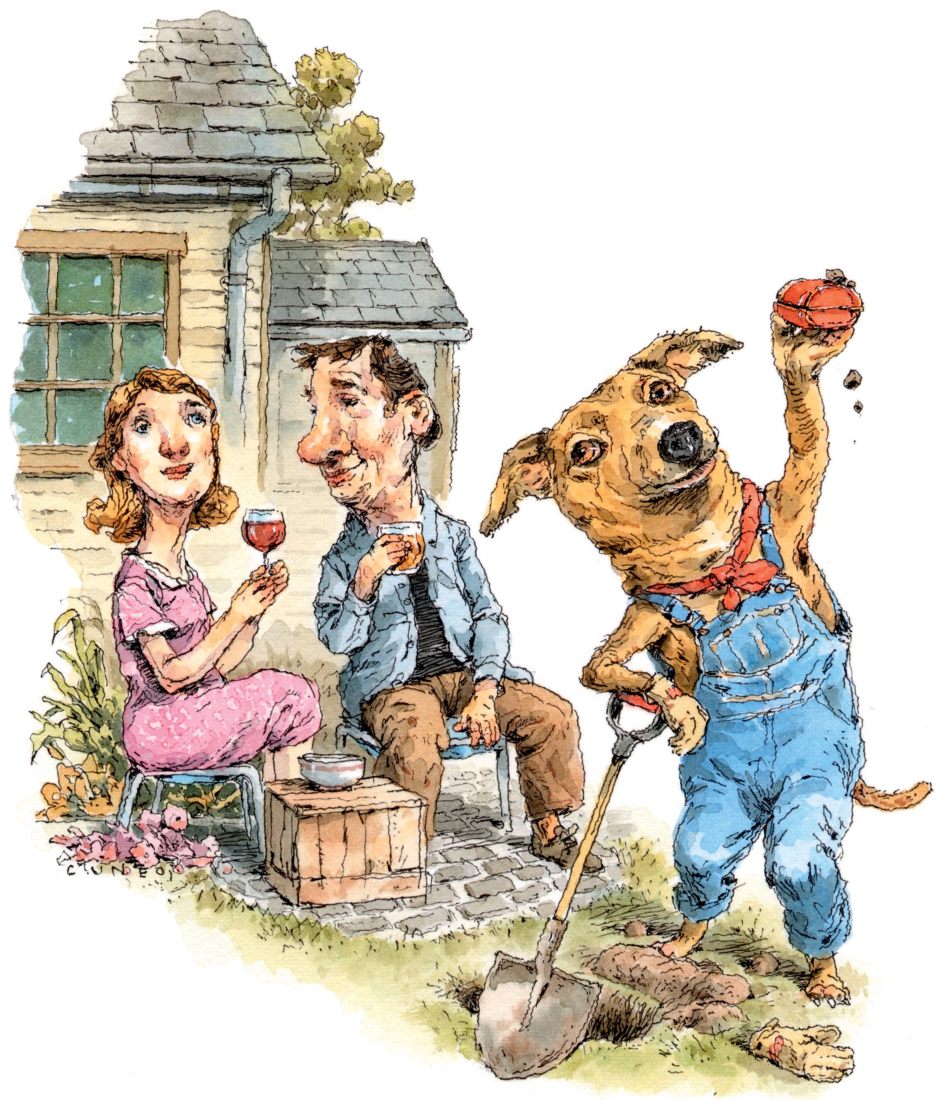

A couple of years went by, and I decided that I could live full-time with this package deal. We signed a lease on a mint-green house with a tomato-red door and a gently concave floor in Cabbagetown, a former mill village in Atlanta. We merged our glassware collections, made exploratory trips to Ikea, and returned some of our beat-up furniture to the sidewalks whence it had come. It was spring, and we were proud of our first yard, so we experimented with gardening. We dug up old marbles and ancient beer bottles caked in red clay. Jerry lazily kept watch from his sun patch in the dirt, emitting a Tom Sawyer–esque satisfaction while we labored.

The three of us spent a lot of time in that yard, mosquito infested as it was, often huddled around a rickety old metal firepit I’d unofficially won in a friend’s divorce. By the time February rolled around, and Dane insisted on spending an unseasonably sunny afternoon sitting out back by the fire, we had our routine down to a science: He would assemble the kindling and light the match, I would retrieve our beers, Jerry would pilfer a choice stick from the woodpile and gnaw on it a few feet away.

But that day, Jerry started digging.

His claws churned methodically. Chunks of clay flew behind him like wood-chipper detritus. His face showed the kind of singular focus he normally reserved for evading capture during fetch. If dogs had brows, his would’ve been furrowed.

Though Jerry had exhibited a smorgasbord of bad behavior in the past, this was a new development. Hoping to nip another questionable habit in the bud, I stood up to reprimand him. But before I could apply discipline, something emerged from the dirt at Jerry’s feet. A box. A box that was red and small. A box that appeared to be distinctively…jewelry sized. I looked at the box, and looked at Dane, and back at Jerry. Both of them were looking at me. Ten seconds later, Dane was on one knee. While I laughed, cussed a little, said yes, and cried, in that order, Jerry stood at our side—just as he would one year later, when we exchanged our vows.

Over French 75s that evening, Dane gleefully explained. Unbeknownst to me, he had spent months training (training!) our recalcitrant swamp urchin to dig not only in one specific part of the yard, but on command, and with a hand signal. This defiant animal, who just the other day had snatched a used toilet plunger from a neighbor’s porch and merrily took off with it lodged in his mouth, learned a secret hand signal. Aided by tenacity and patience and a steady supply of Beggin’ Strips—and moreover, by the primeval and timeless urge to impress a girl—Dane prevailed over Jerry’s feral streak and helped our canine antihero dig up his destiny.

Jerry found treasure after all. I guess you could say we did, too.