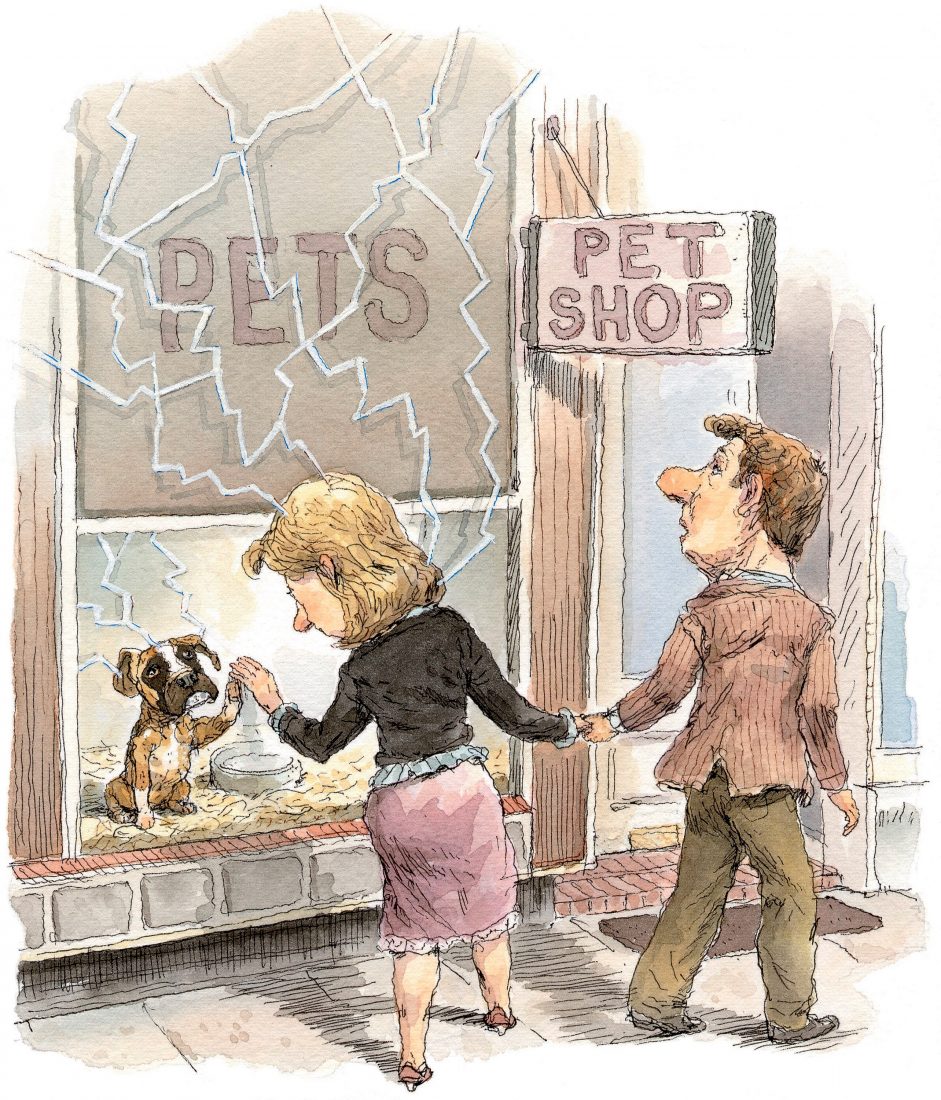

How many rookie mistakes added up to bringing Captain Nemo home? For probably the only time in our married life, my wife and I had turned up early for a restaurant reservation. No, that particular bastion of civility on New York’s Upper East Side could not seat us ahead of time; and yes, it was spitting clots of sleet outside. Somehow, we ended up in the pet store a few doors down, the worst possible refuge, and my wife had gotten amped up. Maybe a little beyond amped. There were, if I recall correctly, actual airborne charges of electrical current sizzling in all directions from her head.

Her eyes had fixed upon a runty, dissolute-looking, vaguely off-brand boxer puppy—the place, we later learned, was a notorious breeding mill—and now her eyes were fixed on me. Here was what I realized: I would leave the store with that boxer puppy, or without that wife. Here was what I couldn’t know: A few years down the road I would have neither one.

What I remember from the rest of that night was a fluttery, aghast feeling that one could just waltz out onto the sidewalk in full possession of a living creature and have no real clue what it might require of you. (It’s like leaving the hospital with your first child—shouldn’t I need a license for this thing?) As two expatriate Southerners—from New Orleans and Atlanta—we had grown up with dogs you let in and out the back door, not dogs you smuggle into a Brooklyn walk-up who then commence wailing like banshees.

Captain Nemo—he acquired his name basically out of the blue during the cab ride home—turned out to be a jolly, relentless little soul, with many of the characteristics you’d check off for a job interview candidate: self-starter; didn’t allow himself to get hung up on past mistakes; nothing if not all-in. My early reactions to him carried a simple refrain: I can’t do this.

“I can’t do this” when he cried all night. (I remembered my mom wrapping a clock in a puppy’s blanket to remind him of his mother’s heartbeat. Okay. Just try finding a clock these days that actually ticks.) “I can’t do this” when it was payback time—which is to say every time we left Nemo alone in the apartment, which he would then ransack.

There was the morning I just wanted to get the paper and a cup of coffee without losing another sofa cushion. Why not close him up in the bathroom? Genius! Or so I thought as I returned, my heart filled with song, maybe fifteen minutes later. Opening the bathroom door, I was almost physically slammed backward by a vicious stink.

Dog crap was smeared like scorch marks up the walls to the height of his outstretched, jumping paws. Frantic claws had tattered the toilet paper to confetti and gouged slashes of paint off the inside of the door. It was…a prison riot. A one-dog, bathroom Attica.

We collected advice. My brother—the Hunter—sent his dogs off to obedience school in Michigan; it didn’t cost much more than a year at Andover. I didn’t have to check my bank balance to know we wouldn’t be taking any dad-and-dog trips to the leafy Midwest. No, we called the Penny Man.

On the phone, his requirements were simple: We were to have ready an empty plastic water bottle, ten pennies, and $100 in cash. Friends said he was a magician with stubborn puppies. Given his basso profundo West Indian accent, I imagined him getting some Baron Samedi mojo cooking with the pennies and bottle. He arrived, an enormous man, door-filling, his bulk exaggerated by the overstuffed down parka he never removed.

Receiving the ritual objects, he poured the pennies into the bottle, and motioned for us to stand back. Nemo was riveted as the Penny Man bent down to him. “Yah!” screamed the Penny Man, sending our little puppy ricocheting off the walls. “Yah! Yah! Yah!” he shouted, shaking the bottle over his head like a weaponized maraca as he chased Nemo, round and round through the living room and back down the hall. My wife and I were freaked out, transfixed. Pulling up after circuit four or five, his brow pumping sweat (he had to be hot in that coat), the Penny Man ceremonially handed over the bottle. “Shake this; he’ll do whatever you want.”

We would do no such thing. We had only to picture Nemo quivering in the hallway to swear off the bottle forever. Instead, we focused our resolve in the opposite direction.

Now before we walked out the door—before, in fact, we took a coat off a hook—we would get down on the floor for a little head patting and soothing: “I’m going out now, Nemo. I’ll be back in five minutes/tonight/when the moon is in the seventh house.” Whether it was the transition therapy or he had simply attained the confidence we all wish for with maturity, the craziness ceased. He had us, in other words, pretty well trained.

He was our only child. This became clear in almost parody form the day I bought the Snugli. It seemed perfectly reasonable to me to strap a puppy to my chest in a baby carrier. It was a mile-long walk to my writing studio every morning, after all, and life was too short to drag him like a pull toy.

But it was too much for the Italian grandmothers of Cobble Hill. Out on the sidewalk one kindly, infant-loving lady lifted the blanket I’d put over his head before I could say anything—“O my Go-awwwd!” she screeched. Soon, we were neighborhood celebrities, anticipated up and down the stoops of Henry Street, one pewter-haired, black-smocked humorist recruiting the next: “Go see his pretty baby!”

We became buddies, Nemo and I, two gentleman freelancers charting our own course: a leisurely walk to work in the morning, say, and the dog run at lunch. Never a show-dog candidate, he grew into a handsome fellow in a boxery way, fawn-colored with a black mask, droopy-faced, of course (those wrinkly muzzles bred to keep blood away from boxers’ eyes when carrying game in their mouths), nimble and athletic. Among my enterprises at that time was writing a syndicated wine column, and the studio floor was often packed wall to wall with bottles, leaving only the narrowest corridors to edge through. Nemo, bouncy, rough, and rowdy by nature, picked his way among the bottles like Baryshnikov.

Then came the days when my wife and I grew apart, and I moved up to the studio without him. I had custody only every other weekend or so. The weeks became months; the situation became permanent.

Cut to the former couple’s fumbling first attempts at dating new people:

Him: A new girlfriend is trying to light my kitchen stove with a match and the gas valve turned way too high. From the next room I hear a boom! and a yelp from Nemo, who had snuck up unseen beside her. Nobody is hurt, but Nemo’s whiskers are frizzled, his eyebrows singed off. He looks comically like Mr. Potato Head before you start adding facial parts. I feel weirdly guilty as I deliver him home, claiming I was the one who lit the stove. My wife is looking at me like, yeah, well, fifteen years down the road and you still don’t know how the stove works here, either.

Her: She takes Nemo out for a long, long walk to settle him down before she invites a new man over. The guy arrives, she pours two glasses of wine, and as they sit down side by side on the sofa, Nemo marches straight up to her, looks her in the eye, and fire-hoses all over the rug at her feet. That’s my boy!

We had decided, she and I, to be nice to each other, as nice as the process of divorce would allow. Not contesting custody of Nemo, my old office mate and running buddy, was the coinage I paid down in niceness.

I had been seeing less and less of him when I kept him for one last weekend. I was taking him back on a bright, crisp September morning, crossing Atlantic Avenue, when I saw a clutch of waiters spilling from the restaurants and shouting and pointing: Across the river a tangle of smoke was boiling from one of the World Trade Center buildings. Nemo and I raced to the apartment. I sat beside my wife, watching on television as the second building came down. Maybe we held hands.

When we finally stepped outside, the wind had carried charred ledger pages from Cantor Fitzgerald into the back garden. White ash had settled so thickly over everything that cars on the street appeared to be made of papier-mâché. The three of us walked and walked, Nemo, as always, nuzzling close between us, an affectionate, leg-tangling tripping hazard. We stood for a long while on the Promenade, staring out across the river.

At last, I kissed her on the cheek, kissed Captain Nemo on the head, and turned away from one home and toward a new one. I was aware of the world shifting out from under me, and the past, always unbridgeable, rose up suddenly across a great divide.