Henry E. Davis was a renaissance man with a lifelong passion for hunting. Perhaps best known for his book The American Wild Turkey, published in 1949, Davis was a highly respected South Carolina attorney, a historian, an avid horticulturist, and a builder of fine furniture. He also crafted a variety of turkey calls and small-caliber sporting rifles.

In his lifetime he assembled more than eighty rifles, having them rechambered and combined with barrels, which had been rifled to his specifications. They were bedded in handsome checkered stocks he made himself. But no gun was more famous than Davis’s W. W. Greener, which he often called Old Betsy. The shotgun figured prominently throughout his book and other writings. It was a piece of hunting history: seven pounds, twelve ounces of pure Siemens-Martin steel and marbled Jura walnut fashioned into an elegant and graceful firearm.

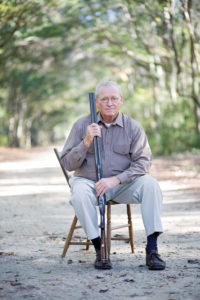

Photo: Julia Lynn

The author cradles the Greener.

Family Ties

I’d been fascinated with Davis’s Greener ever since I learned that my family’s past had intertwined with the gun a century ago during a session of court being held in Moncks Corner, South Carolina. Henry E. Davis, then a thirty-year-old lawyer from Florence, was there to try a lawsuit. Over the course of several days, during breaks in the trial, he spent time with Sumter attorney Marion Moise, my great-grandfather, who was almost twice Davis’s age, discussing subjects of mutual interest: hunting and shotguns.

In his conversations with Moise, whom Davis described as having the reputation of being one of the most expert performers with a shotgun in the state, Davis informed Moise of his recent decision to obtain a new gun and told him that he would consider it a great favor if he would give him some advice on the subject.

Davis wrote in his memoir, “Without hesitation, Moise stated that he considered the W. W. Greener to be the best shotgun made and urged me to have one made to my specifications.” Impressed with his colleague’s firm endorsement, Davis made up a list of exacting specifications, which he sent to a sporting guns dealer in New York. He ordered the Greener with two sets of barrels: one 30 inches and the other 27 inches. Each barrel of the longer set had 2¾-inch chambers and both were choked full. The barrels were specifically choked to shoot an 84 percent pattern with small shot as well as buckshot, at forty yards. The barrels of the shorter set were choked full and improved cylinder. The order was placed in the early part of 1910, and the gun was delivered to him in October of that year.

Photo: Julia Lynn

The well-worn engraving.

In 2008 I undertook the task of editing a collection of Davis’s unpublished works. Originally titled Old Betsy: Stories of Hunting with the Old Percussion Muzzleloader and Its Successors, the typed manuscript contained a remarkable series of tales of hunting deer, turkey, ducks, partridges, and other beasts of the field and forest during the last decade of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth. In my quest to find suitable illustrations for the book, I began contacting the descendants of Davis’s friends, one of whom was Alexander (Alex) McQueen Quattlebaum, Jr., of Charleston and Arundel Plantation near Georgetown. Quattlebaum not only invited me to accompany him to the plantation to search through drawers for old photographs, but he also told me he had inherited an old gun from his father that had once belonged to Henry Davis. My curiosity was piqued, to say the least.

Arundel is a 1,140-acre former Pee Dee River rice plantation where Davis had frequently hunted. And while the search for photographs proved fruitless, the shotgun Quattlebaum handed me was the Greener that Davis wrote so fondly of, complete with the correct serial number and the extra barrel set. It was in extraordinarily good shape and as tight as the day it was delivered to Davis ninety-nine years before.

On the trip back to Charleston, Quattlebaum invited me to return in the spring and use the gun to take a turkey. That meant I had around four months to mentally prepare myself and stew over the enormity of such an event. I even inquired among my hunting friends about where I could find period shotgun shells similar to the ones Davis described in his memoir. In response, a bird-hunting buddy gave me a small bag of 1940s- to 1950s-era 12-gauge 2¾-inch paper shells loaded with number-five shot.

On the Hunt

I arrived at Arundel’s oak avenue by mid-afternoon on April 6. Alex Jr., the owner of Arundel and the Greener, was away, but his son Alex III was my genial host. He showed up moments later and, to my delight, asked if I would like to go out that afternoon and turkey hunt with the Davis Greener.

I quickly collected all my garb and gear, pocketed the ancient shells, took possession of the revered firearm, and after donning my well-used ghillie coveralls and booney hat, headed out for the plantation’s piney woods across Plantersville Road. Scattered throughout the pinelands were managed food plots, one a long chufa patch bordering a tangled thicket of trees along the edge of a ditch. On the opposite side of the chufa patch was a flooded Broomstraw field, which offered little opportunity for cover. I elected to take a drier position on the edge of a dirt path at the top of the field. As exposed as I was, the ghillie suit pretty much formed its own blind. I carefully limited my movement to making occasional yelps on my resonant little box call and returning to holding the gun ready in my lap.

After managing three yelps in forty-five minutes, I detected some motion a short distance over to my left and could make out the forms of two birds standing there, necks stretched, and staring at me. It took an agonizingly long time for me to twist my head enough to check out whether those birds were wearing beards and an equal movement of excruciatingly slow motion to raise my gun where I was looking down the barrels at two young but substantial gobblers.

For the better part of a minute, they were too close together to risk a shot, and they seemed to be getting very suspicious of whatever they thought I might be. They were off about sixty feet and were not coming any closer. They turned around, as if to depart, and managed to separate by a few feet. I let fly those vintage number fives and took the larger bird of the pair in a clear affirmation of that gun’s 84 percent pattern.

Admiring that fine bird while holding Davis’s “Old Betsy,” I allowed myself a brief shout of exultation and remained there for some time savoring the moment, knowing that I had reproduced the experience its renowned former owner enacted a century earlier, using the same gun for the same quarry in the same territory. That young gobbler formed the centerpiece of a fine meal in the company of good and cordial friends, and the storytelling began anew.