People leave strange offerings on the sidewalk outside Randall Andrews’s studio. Busted table legs, old doorknobs, rusted bits of tin—clutter to most, but raw material to Andrews, an artist who makes large-scale installations out of the junk his neighbors throw away. “Everything has a story; all those pieces of wood, they talk,” says Andrews, who started collecting scrap eight years ago, after he moved back home to Clarksdale, Mississippi, from Los Angeles. “When I saw how much of the Delta was vanishing from before my very eyes, it became a sort of quest to salvage as much as possible.”

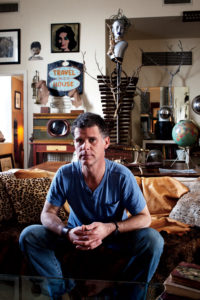

Photo: Andres Gonzalez

Andrews in his apartment inside a converted bank building.

That quest has resulted in bold mixed-media pieces, some as heavy as eight hundred pounds, which simultaneously recall and reinterpret the region. Though Andrews’s work hangs in private homes and businesses from Carmel to Memphis, he’s best known for transforming the interiors and exteriors of the blues town where he was born. He has made signs for a liquor store out of old marquee letters, motorcycle chains, and bookshelf braces, and a bar for the New Roxy music venue out of bamboo, cypress, and old ceiling tins. In August, Andrews’s friend and collaborator John Magnusson is set to open Chateau Debris, a downtown guesthouse that will also serve as a de facto gallery for the artist’s work.

Mostly monochromatic, Andrews’s pieces are driven by composition and texture, much like the geometric sculpture of the late Louise Nevelson. His art can feel organic, all bleached wood and rust, as easily as it can seem futuristic, with tractor gaskets, LPs, and bedposts painted white or gold. He’s equally drawn to antebellum columns and mid-century vacuum cleaners shaped like rockets. And he can spend hours telling stories about each object; one friend describes him as “Eudora Welty on speed.” “He’s the best of what the Delta is,” says Marilyn Trainor Storey, a Jackson-based interior designer who works in Clarksdale and frequently incorporates Andrews’s pieces into her projects. “A conglomeration of artsy and cutting-edge cool but down-home and earthy at the same time.”

Photo: Andres Gonzalez

An outsize work made from gold-painted LPs.

Though he has long admired design and found-object art, Andrews came late to his current medium. Originally trained as a chef, he moved to Los Angeles after culinary school in 1994 to take a job as the personal assistant for actress Annie Potts. Later, he worked as a personal chef and in television production. “I did everything in Los Angeles twice except make money once,” he says. In his free time, he took photographs of the city. Eventually, Andrews burned out on the L.A. grind, so he packed up and came home. Those first months back in Clarksdale made him feel as if he’d escaped a cage. He took pictures like mad. He scavenged wood and metal. He drove the back roads and stopped in fields to marvel at his solitude. “I went bananas just rediscovering the Delta,” Andrews says. “I had to step away from here for twenty years to be able to appreciate it again.”

Slowly, his following is growing. Last year, Nina Miller, the executive director of the Gibson Foundation, the charitable arm of the guitar company, bought two Andrews pieces to take home to Nashville. “There’s something about Randall’s stuff,” Miller says. “I wouldn’t call it dark. It’s definitely haunting. It pulls you in.”

And that’s part of Andrews’s goal, to spotlight the beauty inherent in even the Delta’s most broken and forgotten bits. “How does a generation pass the torch in this town?” he asks. “It’s up to the next generation to pick it up and carry on.”

For more information, go to facebook.com/deltadebris.