I recently found myself chatting with Anthony Scanio, the chef de cuisine at Emeril’s Delmonico, on St. Charles Avenue in New Orleans. Scanio has a supremely cool house-made liqueur program going at Delmonico, where he makes an arugula liqueur; a bay leaf liqueur; a blood orangecello; a walnut nocino; and an “elixir of the Seven Powers” that he flavors with saffron, mint, anise, and orange flower water. The program’s inspiration, he told me, derived from two places: Italy, where Scanio spent a year of culinary study, and where, he said, a “culture of homemade liqueurs remains very vibrant,” and his hometown, New Orleans, where a formerly vibrant culture of homegrown liqueur making has mostly disappeared.

“It’s a lost part of our Creole culture,” he lamented, citing a chapter from early editions of the canonical The Picayune’s Creole Cook Book (first published in 1901) that featured dozens of liqueur and cordial recipes for the home bartender. A liquor becomes a liqueur (or cordial) via the addition of flavorings and sweeteners after distillation, a very kitchen-friendly enterprise. Prohibition was the primary culprit for the practice’s demise; it was certainly the cause for that chapter’s excision from subsequent editions. “What we’re doing is just a recuperation of our old Creole ways,” Scanio said. “Just look at Southern Comfort, which began here as a local liqueur before becoming this strange industrial product.”

So I did. You’ll forgive me, I hope, for having forgotten Southern Comfort’s origins in New Orleans, despite that its label proudly trumpets it; my brain tends to geocache it in Alabama, thanks to the Slammer, or in states like Wisconsin and Pennsylvania and Illinois, which (along with Florida) consume the highest volume of the liqueur. It seems more Southern-y than Southern. But Southern Comfort was indeed invented in New Orleans, at a bar called McCauley’s, in 1874, by a barman named M.W. Heron. Chris Morris, the master distiller at Brown-Forman, which owns the brand, explained it to me this way: “Heron began making this drink in batches, the way bartenders might make pitchers of margaritas today.” Heron called it Cuffs and Buttons, probably to distinguish it from, and maybe align it with, a popular local drink called a Hats and Tails. No one knows what went into a Hats and Tails. And just a few people know what went into Heron’s Cuffs and Buttons.

In the Brown-Forman archives, Morris said, is a “single-page typewritten document from Heron’s assistant,” dating back to the turn of the century, after Heron had decamped to Memphis and was bottling his formula as Southern Comfort. The document roughly lays out the early recipe: Into a quart of whiskey went vanilla, cinnamon, cherries, citrus, peach brandy, and, well…Morris apologized, in a way, for being vague: “The reason I’m not telling you the whole recipe is because it’s a corporate secret, like Colonel Sanders’s recipe.” Morris himself isn’t even privy to the current formula, which nowadays starts with a base of grain-neutral spirits rather than bourbon, and is fully known “to only two people, who aren’t allowed to travel together.”

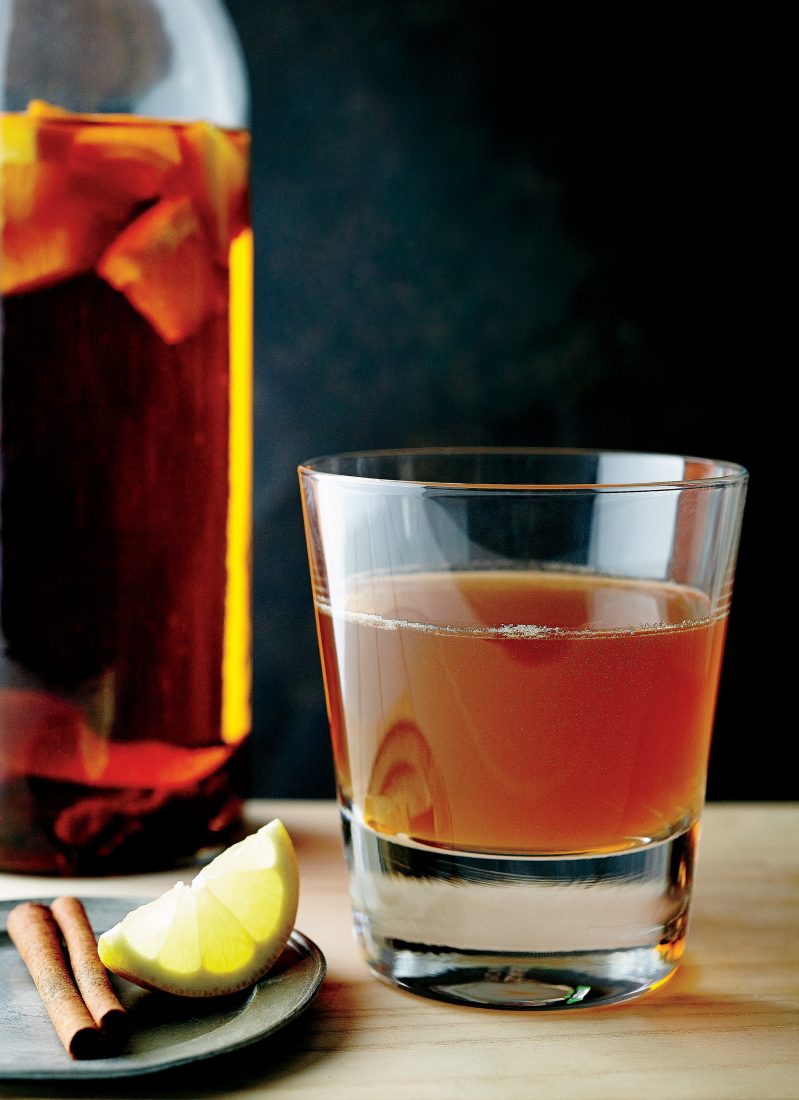

But Morris revealed enough of Heron’s original blueprint for me to embark on the kind of playful experimentation that Scanio does at Delmonico. Liqueur making, as Scanio said, “sounds all mysterious,” but it’s fundamentally a simple infusing process, plus sugar. “The fun is in the alchemy,” he said, and it’s true. The accompanying recipe is my approximation of what Heron might have served at McCauley’s in the 1870s. I started with 92-proof Redemp-tion High-Rye Bourbon, to offset the sweetness I’d be adding, and doctored it with the fruits and spices Morris revealed, along with dried apricot to heighten the stone-fruit notes you find in Southern Comfort. After a week of infusing, I mixed the strained bourbon with honey and some oldfangled peach brandy from Peach Street Distillers. (Cut back on the honey dosage if you use something like Hiram Walker peach brandy, which is viscidly sweet on its own.)

The result didn’t quite taste like today’s Southern Comfort but vibrantly evoked it, which may or may not mirror the relationship between modern SoCo and Heron’s Cuffs and Buttons. Yet it was outrageously good, reminiscent of, say, a spiced peach old-fashioned, with startling depths of flavor. “Making liqueurs is simple but transformative,” Scanio said, adding that, after the surge of DIY bitters making in the last several years, “this could be the next step.” Cuffs and Buttons in hand, I think Scanio’s forecast is right. As for my next step: I’ve got an original edition of The Picayune’s Creole Cook Book to track down.