“You see those woods over there?” says Ben Crenshaw, the silver-haired two-time Masters winner, World Golf Hall of Fame member, and lifelong resident of Austin, Texas. “When we were kids, we hung out in there and drank beer a time or two.” He betrays a sly smile. A time or two. Right.

Crenshaw sits at a paint-chipped picnic table outside the humble tan-brick clubhouse of Austin’s Lions Municipal Golf Course (“Muny,” if you’re local) with the actor Luke Wilson, star of such movies as Old School and The Royal Tenenbaums. Muny lies about three blocks from the home where Crenshaw grew up. He started playing here in 1960, at age eight, when he would walk over from the house with his brother, Charlie. He won his first trophy here as a fourth grader, shot his first hole in one here, has played the course more than a thousand times.

But Crenshaw is not at Muny today to shoot an unlikely buddy comedy with Wilson. He’s here because the Austin institution—one of the country’s most important public golf courses—could be shut down in 2019, razed for residential and commercial development. Muny, which traces the contours of Lady Bird Lake just two miles from downtown Austin, is a 141-acre oak-studded oasis of calm smack in the center of one of the country’s fastest-growing boomtowns. Losing it, says Crenshaw, would affect not just the city’s golfers but the entire community, not to mention the deer, foxes, armadillos, and other wildlife that call it home. “Imagine New Orleans without City Park, or Houston without Memorial Park. It’s the same thing.”

Muny is also a civil rights landmark. Back in 1951, three years before Brown v. Board of Education, two black children who lived nearby defied Jim Crow laws and walked onto the course one morning to play a round. While they were out there, word made it to the mayor’s office about what was going on, and city officials decided to let them play on, unofficially making Muny the first desegregated public golf course in a Southern state and drawing black golfers from other parts of Texas to play.

So why would Muny possibly shut down? The answer, of course: money. The land that it occupies was donated to the University of Texas at Austin in 1910 by a former regent. The local Lions Club leased the land from the university in 1924 to open the city’s first public course, and a dozen years later transferred the lease to the city, which currently pays about $500,000 per year to use the land. And there’s the rub: Public universities around the country have faced budget cuts, and the University of Texas System estimated in 2011 that the land might be worth $5 to $6 million per year at market rates. That year, the UT Board of Regents voted to allow Muny’s lease to expire in May 2019.

Ever since that decision, Muny has become a cause célèbre in Austin, and a nonprofit organization named Save Muny has become the organizing force, recruiting local notables such as Willie Nelson and his son Lukas to help with the efforts. Which brings us back to Luke Wilson. The forty-six-year-old grew up in Dallas, and his two brothers, Owen and Andrew, both attended UT–Austin. A competent golfer himself, he’s played Muny many times and last year invested in an Austin company, Criquet, that makes retro-looking golf shirts. Criquet adopted Save Muny as its signature cause and enlisted Wilson to lend his star power. Last April, at Criquet’s annual 19th Hole party, a rollicking fund-raiser for Save Muny, a round of golf with Wilson and Crenshaw went for $25,000 at auction, raising enough to cover the nonprofit’s annual operating costs.

Photo: BRENT HUMPHREYS

Both Crenshaw and Wilson have played many rounds at the venerable course, which was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2016.

“When I first started coming to Austin, it was so great because you could hang out all over town,” Wilson says in his laconic drawl. “There was no traffic. It was a different city than it is today. Now everybody’s moving here, but this place”—he looks around at the heritage oaks blocking views of the mirrored high-rises nearby—“this place is a mainstay. It’s so much more than a golf course.”

As Crenshaw and Wilson chat, a group of boys and girls from a local high school shares the driving range with a tattooed guy whose long rocker hair spills over his black T-shirt. Countless golfers stop to introduce themselves to Crenshaw, and at one point a man with shaggy blond hair rolls up in a golf cart with his cattle dog at his side (this being Austin, Muny is dog friendly); he plays here once a week, usually barefoot, and it turns out he and Wilson are old high-school buddies. “This is what I’m talking about,” Crenshaw says. “Look around and you see all different walks of life interacting with each other and learning and enjoying this ancient game.”

Noël Bridges, one of the leaders of the Save Muny movement, says that she often hears from mothers of children who play golf but can’t afford to join a country club. “This is one of the only places they can play,” she says. “And the minute you take that away, golf becomes out of reach for so many people.” Considering that the game has long carried a reputation for exclusivity, that potential effect is especially troubling to Crenshaw.

Thanks to the work of Save Muny, the course was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2016. That was a big win, but largely a symbolic one, because even that designation can’t prevent the course from being bulldozed. More important, earlier this year three state senators proposed a bill that would transfer ownership of the land from UT to the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department. The bill passed with bipartisan support in the Senate but then never emerged from committee in the House. The threat of losing the land entirely, though, with nothing to show for it, has brought the university to the bargaining table. Its first offer to the city—fine, keep the golf course but pay us market rent—had no chance of acceptance. But now the mayor and the university’s president, Gregory Fenves, are haggling over more creative solutions such as a land swap, where the city could take over the golf course and the university would get some other acreage it could turn into dollars. “UT does not believe it is fair that the cost of maintaining the use of the property as a golf course should be borne just by the university, and the students who pay tuition,” writes Fenves in a statement to Garden & Gun. “Based on the progress of our talks with the city, I’m hopeful that a fair resolution for all is possible.” If not, the bill will be reintroduced in the next session.

Photo: BRENT HUMPHREYS

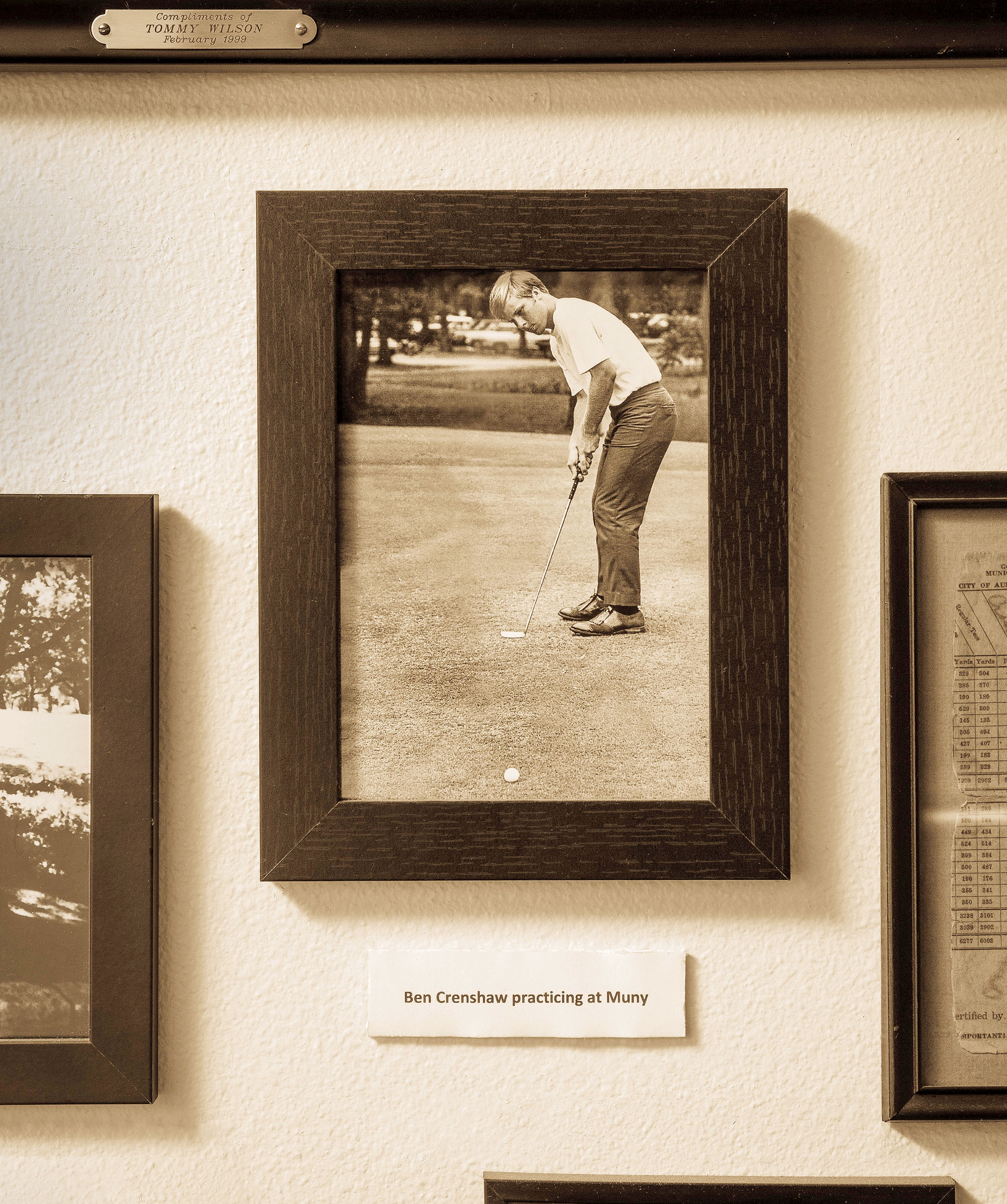

Vintage photos line the hallway of Muny’s clubhouse, including this shot of a young Ben Crenshaw.

Crenshaw, for his part, is confident that victory is finally within sight, and he’s already laying plans for what’s next for Muny. Inside the old clubhouse, in a narrow hallway between the dinky snack bar and the pro shop, a wall of yellowed photos depicts the course’s history (including one of a strapping young Crenshaw with fellow Texan pro golfer Tom Kite). There also hangs a rendering of a Muny course renovation that would bring it back to its original layout, increase the practice space, preserve the clubhouse, and add a second, modern one. Crenshaw, who has designed some of the world’s best-known courses, drew up the plans for free and promises that he and his allies can raise the money to get the renovation done.

As the sun dips toward the West Austin hills on the horizon, Wilson offers his own parting perspective. “It’s just weird that the future of this place would ride on how much money it’s worth,” he says. “What about all the other kinds of value?”