When I was a boy, in the family car, on a Southern road, we would fairly often drive past a mule going in circles. That mule, my father would point out, was working—turning a mill that ground stalks of sugarcane. The people in the yard were working too—cooking the juice in that open kettle.

Even while he was in that expansive frame of mind, I never asked him to explain Eelbeck.

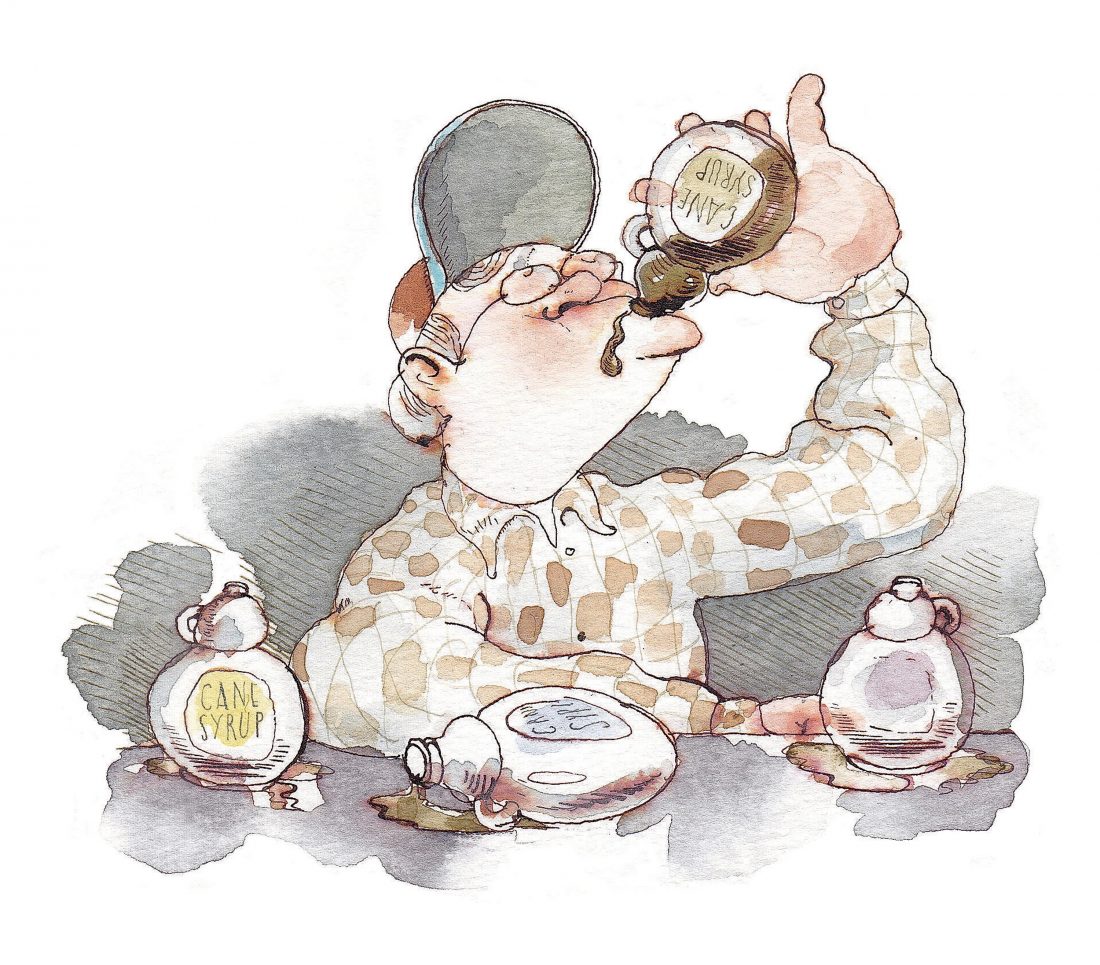

At home we sweetened our waffles with Log Cabin, which was translucent and tasted more or less maple. At my grandparents’ house in Jacksonville, Florida, we had Eelbeck cane syrup, which looked like motor oil overdue to be changed. Eelbeck tasted sweet but also murky. On biscuits with butter, Eelbeck was the strongest thing I had ever put in my mouth. It evoked that unh…unh noise King Kong made when he was running around with Fay Wray. I liked it.

But why “Eelbeck”? The image on the bottle wasn’t bland and reassuring like the log cabin on Log Cabin. As I recall, it was a hillbilly-looking man sitting on a creek bank fishing with a cane pole and at that moment getting an eel on his hook. The eel was labeled “eel,” and the creek was labeled “beck.” The man may have had exclamation points leaping from his head—at any rate he looked like he’d been struck by a lot more than he’d angled for. Maybe the eel was not meant to conjure the power and darkness of the syrup and vice versa, but it worked that way for me. I had not yet heard any song about a blacksnake moan, but I had been in a skiff with a fresh-boated eel lashing and thrashing and twining upon itself, and I had been glad that Daddy, not I, had to deal with it. And what was a beck? I had heard my mother complain of being at someone’s “beck and call.” The call of the eel?

I was never one to pipe up with possibly embarrassing questions. If there was something sufficiently work-related for my father to explain, he would bring it up. That’s the way things still stood between us when he suddenly died. Eelbeck remains one of a number of things I can’t imagine being cleared up in a fatherly voice.

Today, there is the Internet. Online I have learned that beck is just an Old English word for brook or stream. Eelbeck is a settlement in Georgia (now part of the Fort Benning army post) named for Henry J. Eelbeck, who was associated with a mill, built mostly by slave labor, that produced grits and cornmeal as well as syrup. Google provides a faint image for the Eelbeck grits label; a man is fishing, but that is all you can tell. It can’t be the same drawing that preyed on my imagination. The mill no longer produces; the Eelbeck brand is dead.

Cane syrup lives, though. On the Internet it even shines, at least in comparison to the high-fructose corn syrup that gets a lot of blame for American obesity. Too much of any sweetener is bad for you, I gather, but cane syrup is too pricey, in bulk, and too bold, in any amount, to be slipped into the processed foods that seduce the contemporary palate. Pure cane syrup—nothing but sugarcane juice boiled down till it’s deep and dark—lacks the bitter taste of molasses, because molasses is what’s left after sugar is crystallized away. Pure cane syrup retains the sugar plus some of the iron and other nutrients for which people have traditionally taken molasses.

And the big name in pure cane syrup is Steen’s—a staple of Louisiana culture, like crawfish or Fats Domino. The C. S. Steen mill, founded in 1910, still thrives, in Abbeville, Louisiana. Charley Steen III, who runs the mill, is the founder’s grandson.

This was the man, surely, who would talk to me of cane syrup in familial terms. I telephoned the mill and chirped, “Hey, I want to write about your syrup.” Whoever answered said:

“No. No. He doesn’t do any of that. And I know he’s not going to talk to you now, because his father died last night.”

A couple of days later, an obituary of Albert Steen, father of Charley, was online. “He loved to work,” his widow was quoted as saying. “I figured he would die because he worked so hard.” My dad, the same.