I love everything about oysters. And everything about bars. In the presence of the former, seated at the latter, I’m as happy as a box turtle in a shallow ditch. On a recent swing through Athens, Georgia, I grabbed a perch at Seabear, a demi-restaurant in what was once a Coca-Cola bottling plant on the northwestern fringe of downtown. All the right touches appoint the bar. Light from an oyster-shell chandelier spangles taupe brick walls. Heart-pine sconces frame gold curtains. Scribbles that represent current harvests blanket a looming chalkboard.

During the late nineteenth century, when average Americans believed our natural resources were limitless, oyster bars were working-class palaces where beer was cheap and oysters were cheaper. Then came a fallow time. As pollution and overharvesting robbed our waterways of vitality, oysters became scarce and expensive, and oyster bars shuttered or begot hamburger bars. But a renaissance has come. Former harvest grounds are returning, and new entrepreneurs now bank on the bright future of this old restaurant form.

Photo: Rinne Allen

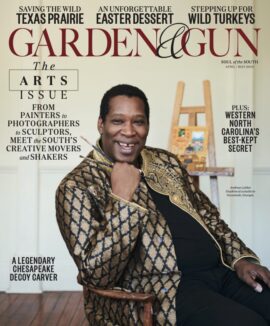

Seabear’s co-owner and head chef Patrick Stubbers (left) with his business partner Peter Dale.

Seabear, which opened in 2014, is a bellwether in the oyster renaissance, an everyman’s drinking and eating parlor for the twenty-first century. Each day, before six and after ten, all oysters on offer sell for a buck fifty: Wild Seasides from Hog Island Bay, Virginia; Sweet Jesuses from Hollywood, Maryland; Naked Cowboys from New York. No matter the time of day, each oyster arrives on a deep tray of pebbled ice with a fluted paper thimble of mignonette, accompanied by a server-led disquisition on habitat, salinity, and where to peg the aftertaste on the cucumbery to coppery spectrum.

This is the second Athens restaurant from Seabear’s co-owner Peter Dale, who also recently launched Condor Chocolates, a confectionery and café in town. Earlier in his career, Dale partnered with Hugh Acheson to open the National, a downtown Mediterranean bistro, beloved for dinner appetizers of Medjool dates stuffed with celery and Manchego, and lunches of harissa-dressed quinoa and other virtuous grains. University of Georgia faculty treat the National like a dining club. Seabear is more of a slurping and drinking club.

On my first visit, I spied Dale on the patio, drinking with friends. I took that as a measure of confidence in his colleagues that he too can steal away to claim a drink and a dozen. That said, the real action is at the bar, where I like to arrive solo at half past five for a dozen raw and a glass of Muscadet, or the tables that stretch along the side wall, where I can hunker with a crew at ten and linger over a couple dozen, a green bean salad garnished with smoked trout roe, a brothy dish of Tybee Island shrimp and grits, a fiery bowl of green curry mussels, and a bottle of Loire Valley rosé.

Photo: Rinne Allen

Steamed Prince Edward Island mussels.

Inspired by survivors from the previous century such as Grand Central Oyster Bar in Manhattan, Swan Oyster Depot in San Francisco, and Casamento’s, the tile-blanketed New Orleans oyster bunker, a broad cohort of new-guard oyster bars now flourishes. This generation shares a commitment to well-made cocktails, a dismissal of folderol, and menus that always seem to include fried chicken sandwiches, shrimp and lobster rolls, avocado toasts, and Parker House rolls.

Seabear manages to be on trend without meekly following that trend. (To make that claim, I chose to ignore its advertisement for Ramen Mondays, pegged at the top left of the menu.) Some fashions are worth embracing, like the frozen Negronis that Seabear serves in short glass bullets. Other bars, including Saturn in Birmingham, Alabama, serve comparable grown-up slushy drinks. But the Negronis that spiral from the machine installed on one corner of the Seabear bar are better than most. Cold as ice-fringed bergs, stout with dry gin, they are as bitter and astringent as high-school love gone bad.

It’s common to mythologize the oyster, to salute the bravery of the first man or woman to crack open a shell, as seeming rock gives way to quivering flesh. I’m a believer in that seduction, a lover of the pomp and circumstance that begins when you take a seat at a great bar, look the shucker in the eye, and call for a clean and cold dozen. In this renaissance moment, new-guard oyster bars require us to make decisions. East Coast or West Coast? Salty or sweet? Deep-cupped and brimming with liquor? Or flat-bottomed and sleek and fluid? And, for those who want to slurp Southern oysters, Chesapeake Bay, Gulf of Mexico, or Lowcountry?

Photo: Rinne Allen

A freshly-shucked Sweet Jesus from Maryland.

Seabear stocks them all, focusing on a rotating roster of six varieties from as far away as Kachemak Bay, Alaska, and as close as Wassaw Sound, Georgia. Here, there are no lesser oysters to consider, no unbalanced cocktails to drink. The only error possible is subscribing to the misguided belief that a Georgia restaurant can’t do right by a New England–style clam chowder. Like much of the menu at Seabear, that sherry-spiked and potato-bobbed soup, spooned between sips of an icy Negroni, tastes like a twenty-first-century standard awaiting canonization.