The decades fall away so easily. I close my eyes and see the boy pulling the red wagon, pretending to be fierce. When he turns the next corner, he knows the beast will be waiting.

I was only six when I got my first job, delivering the afternoon edition of our local newspaper. Every day when I returned home from school, I would lug my wagon around the neighborhood, throwing the rolled-up papers at doorways. In the evenings, I ventured out alone to collect payment from subscribers. I was still learning addition and subtraction, so I had to hand my ledger to my customers and trust them to pay me the correct amount. I was not afraid of these looming adults. What did scare me was the dog who growled and nipped at me from a yard halfway along my route. It’s embarrassing to admit how terrified I was by this animal—he was only a dachshund.

“No, Herman!” I yelled when he dashed around at my ankles. “Go away!”

I was extra small, even for a first grader, and Herman never backed off. I can still hear the clicking of his toenails, his frenzied bark, the wheels of my wagon clanging as I ran.

My anxiety about dogs grew when I was in fourth grade and my father decided to adopt a Great Dane. Thor loved me and my siblings with such enthusiasm that he accidentally knocked down my little sister Susi with his wagging tail. But whoever had owned him before had abused Thor. Every time my father reached to scratch between his ears, the dog recoiled, shaking. Under our care, Thor seemed to grow stronger until one day I saw him throwing up in the yard. The next morning, I found him cold and still, his legs stretched out stiffly. It was the first time I’d ever experienced death.

Next came another Great Dane, a brindle male that my father named Bismarck. Like Thor, Bismarck was gentle with me and my siblings. But if he saw another dog, he lunged. One day while I walked him, we came across an old fat beagle who lived down the lane. When the beagle waddled into view, Bismarck wrenched his leash out of my hand. Before I knew it, our dog had his jaws around the smaller dog’s neck and was shaking him back and forth. I could hear someone screaming, and after a few seconds, I realized it was me.

By the time Bismarck let go, the beagle was dead. Hearing my cries, my father rushed over and pulled Bismarck away. The beagle’s owner, a nice old man who waved whenever he saw me riding my bike, was heartbroken. I couldn’t stop crying and telling him I was sorry, telling him I had tried to hold on. The old man felt so bad for me that he pulled me close and told me that it wasn’t my fault. I never saw Bismarck again. That afternoon my dad took him back to the shelter. “They said they’d have to put him down,” he told me. “A dog that violent will only kill again.”

From that day forward, I was done with dogs. A few years later, when my dad thought enough time had passed, he suggested finding another one. I begged him not to take us back to the shelter. I couldn’t stand the smell of the place, the din of all those desperate animals baying at once. I didn’t want them around me. Just seeing a dog at the park, chasing a ball, made me tremble. When I graduated from college and got married, my wife knew not even to ask. We had two sons, Nat and Sam, and as they grew up, I ignored their repeated pleas for a puppy.

“It’ll be okay, Dad,” Sam said. “I promise.”

I can still see the disappointment in that child’s face, slowly hardening into resignation as he realized I was never going to relent. I would have done almost anything for my boys, but somehow, I could not summon the will to face my fears.

Nat and Sam turned into teenagers. Their mother and I divorced, and the aftermath was so painful that another fear took hold inside me. I vowed that I would never marry again, because I was sure that all marriages were doomed, and I could not bear to allow such chaos back into my life. In ways I could not see at the time, I was steeping in bitterness, sabotaging relationships with good women who deserved more. Every room inside me was going dark, the lights dimming and then switching off, one by one.

I don’t know how Kelley managed to sneak past my defenses. I’m not even sure what she saw in me that made her want to try. In my head, I made an inventory of all the reasons the two of us could never work, and near the top of that list was Kelley’s lifelong love of dogs. She was always fostering rescue animals and often took in pregnant dogs and assisted in the delivery of their puppies. She had a special weakness for breeds others despised, especially pit bull varieties, which she assured me were unfairly painted as vicious.

“They’re the friendliest dogs,” she told me, but of course I did not believe her.

Kelley wanted a ring, a house, a life overflowing with children and animals. I had no intention of sticking around that long. I loved being a father but couldn’t see the point of starting over. I certainly didn’t want any pit bulls. But when I engineered a breakup, I came face-to-face with the emptiness inside me. I realized I was still that terrified little boy, fleeing from a dachshund. Maybe it was time to stop running—from love, and dogs.

I took some time to gather myself, then went crawling back to Kelley. Before I knew it, we were married, and Kelley had plunged me into canine immersion therapy. We had so many foster litters bounding through our backyard that we had to get creative. One bunch we named after James Bond characters, another after The Sopranos characters. Another we bestowed with the names of different cheeses: Brie, Blue, Stinky, Cheddar, Colby, and—my favorite—a little yellow female we called Baby Swiss.

I had to admit, it felt good taking them all in and offering them a haven until they grew big enough for the local shelter to adopt them out. And Kelley was right. The pit bulls were easily the sweetest creatures we cared for, so eager for contact that they constantly leaned against our legs and jumped into our laps. And yet so many people bought into the stereotype of pit bulls that they often went unclaimed. Browsing Petfinder one day, Kelley saw a female pit mix who had languished for so long that she had been scheduled to be put down that day. Something about this girl, in particular—her deep brown eyes, her smooth brown-and-white coat, pointed ears that stuck up like a bat’s—spoke to Kelley. She called right away to request the dog before they put her to sleep.

We named her Muppet, and even I could tell she was special. She adored Nat and Sam so much that when they came home from another day at high school, she whined with joy. I joked that if an ax murderer were to sneak into the house in the middle of the night, Muppet would lick his toes and welcome him into the family. She rarely barked and never growled. When we fostered another litter of puppies, Muppet let them climb all over her, patient even when they tried in vain to nurse, pulling and nipping at her chest.

In those early days, before we had a chance to train her, Muppet had a habit of bolting up to any stranger walking down the street, wanting to say hello. Through most of my life, the sight of a dog breaking free to hurtle toward a target would have made my stomach churn. But now I was married to Kelley, who could read dogs like no one I’d ever known. She could tell from a glance if the retriever down the street was contented or nervous. She radiated authority and kindness that calmed even the most skittish poodle—or husband. Day by day, Kelley was teaching me to read dogs, too, and though I would never know anywhere near as much as she did, I discovered that being around the animals, and Muppet in particular, made me happy.

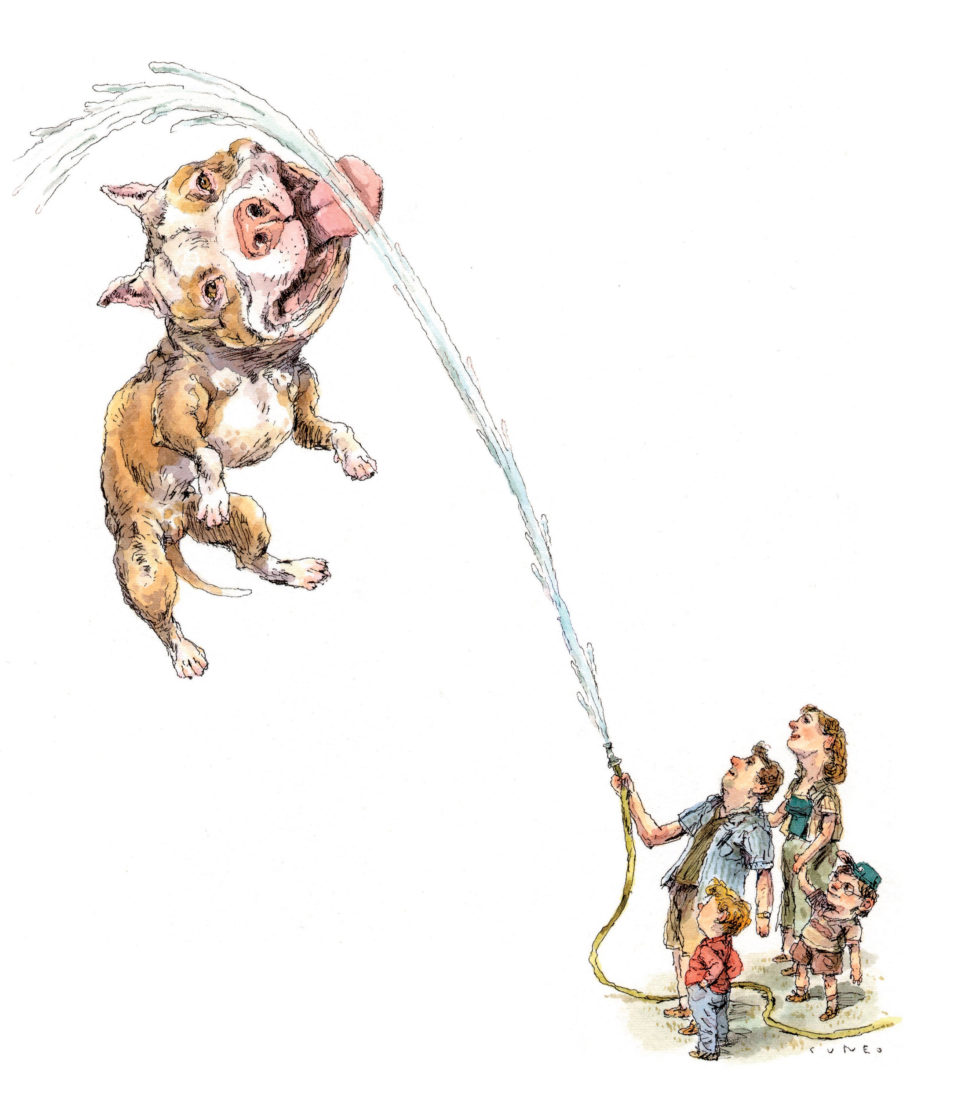

Soon, Muppet and I were taking naps together. The boys and I were throwing her a tennis ball and admiring how high she jumped to gulp mouthfuls of water spraying from a garden hose. We wrote a song about her and serenaded her in the kitchen. If one of us was upset, Muppet sensed our distress and lavished us with attention.

One afternoon, we gathered in our walk-in shower to watch another foster dog deliver her puppies, each wet and squirming and still encased in its sac. Sam grew dizzy and had to leave. If the mom didn’t open the sacs herself, Kelley would pull off the slimy casings and rub the new arrivals in a warm towel.

One by one, she handed the puppies to me, and I studied their scrunched-up faces, each different, each the same. I heard someone laughing, and realized it was me.