Reluctantly, I have come to accept the fact that on certain stormy nights our forty-five-pound dog, overwhelmed by fear, will triumph over a pair of gimpy knees, jackknife into the air, and crash-land onto the tall bed that my wife, Jessica, and I share—scaring the absolute bejesus out of me. No matter how many times it happens, I always catapult forward, eyeballs bugging and heart thumping, until a feverish stabbing of paws, seeking a space for burrowing into, tells some primitive part of my brain that once again we have not suffered a home invasion. It’s only Rosie.

It’s on nights like these that I wonder anew just how we got saddled with a dog with a canine version of PTSD.

It happened like this: One day Jessica went to pick up our then fifth-grade daughter, Hazel, from school. “Mommy,” Hazel began. “I know you’re going to say no, but Mrs. Bradshaw…”

Mrs. Bradshaw being Hazel’s science teacher, Jessica interrupted, “If it’s a rat, we’re not taking it.”

“It’s not a rat,” Hazel said.

“I don’t do gerbils or mice either,” Jessica quickly threw in.

“It’s none of those,” Hazel said, smiling. “It’s a dog.”

Abandoned in the vicinity of Gulfport, Mississippi, in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, the dog was a three-month-old malnourished puppy, a fearful and unlikely candidate for survival, when she was mercifully scooped up by big-hearted veterinarian Betty Baugh Harrison, based in our hometown of Richmond, Virginia. In three trips to the storm-ravaged Gulf, Harrison and her team of volunteers returned, via truck, trailer, and even plane, with 125 dogs, 80 cats, and a horse named Navajo, many injured and all needing TLC.

A call went out to Hazel’s school as well as area adoption groups for “temporary” homes, and the next thing I knew I was standing in the crowded parking lot of Betty Baugh’s Animal Clinic surrounded by dozens of cages holding homeless dogs of all shapes and sizes. Jessica and Hazel were out of town, but my three other daughters—Grace (then ten), Willa (eight), and Nora (six)—had converged on a cage in which a scrawny puddle of golden-red fur with white flourishes cowered in the corner. Out of the cage, the frightened puppy arched her back, head lowered. Her tail wagged along with her entire rear end. She had bouncy Yoda ears, and in the middle of a white muzzle, black lips that curved up, like the Joker’s but in a good way, so that you would swear she was smiling at you.

Surrounded by so many possibilities, Grace and Nora explored, but Willa, the most stalwart, stayed right by that cage, fending off would-be suitors. Harrison told us the pup was a female Lab-chow mix. This being Lab and Volvo country, I secretly suspected the Lab part was just a clever ploy. But it didn’t much matter. Willa wanted that dog.

Before we left the parking lot, I—like my father before me, an inveterate nicknamer—had dubbed our spindly new pet Cajun Hasenpfeffer, the name of the rabbit stew that a cartoon king wants to turn Bugs Bunny into during a famed Bugs–Yosemite Sam episode. Instead, the king is hoodwinked by the clever rabbit. The label would prove to be apt.

Our skinny new pal may have charmed us with her perpetual grin, but if she was happy to find herself in a safe and loving environment, she had a funny way of showing it. When I put her down in our house, she ran under a coffee table and hid. The girls named her Rosie.

Already living in a house with five females, I wouldn’t necessarily—given a choice—have added a female dog into the mix. As it turned out, Rosie wasn’t so keen on having me around either. Though she had her secrets, like her exact age and lineage and her trials during the storm, we soon surmised that she had been through a lot in her short life and had many fears. But the thing she feared and loathed most of all was men.

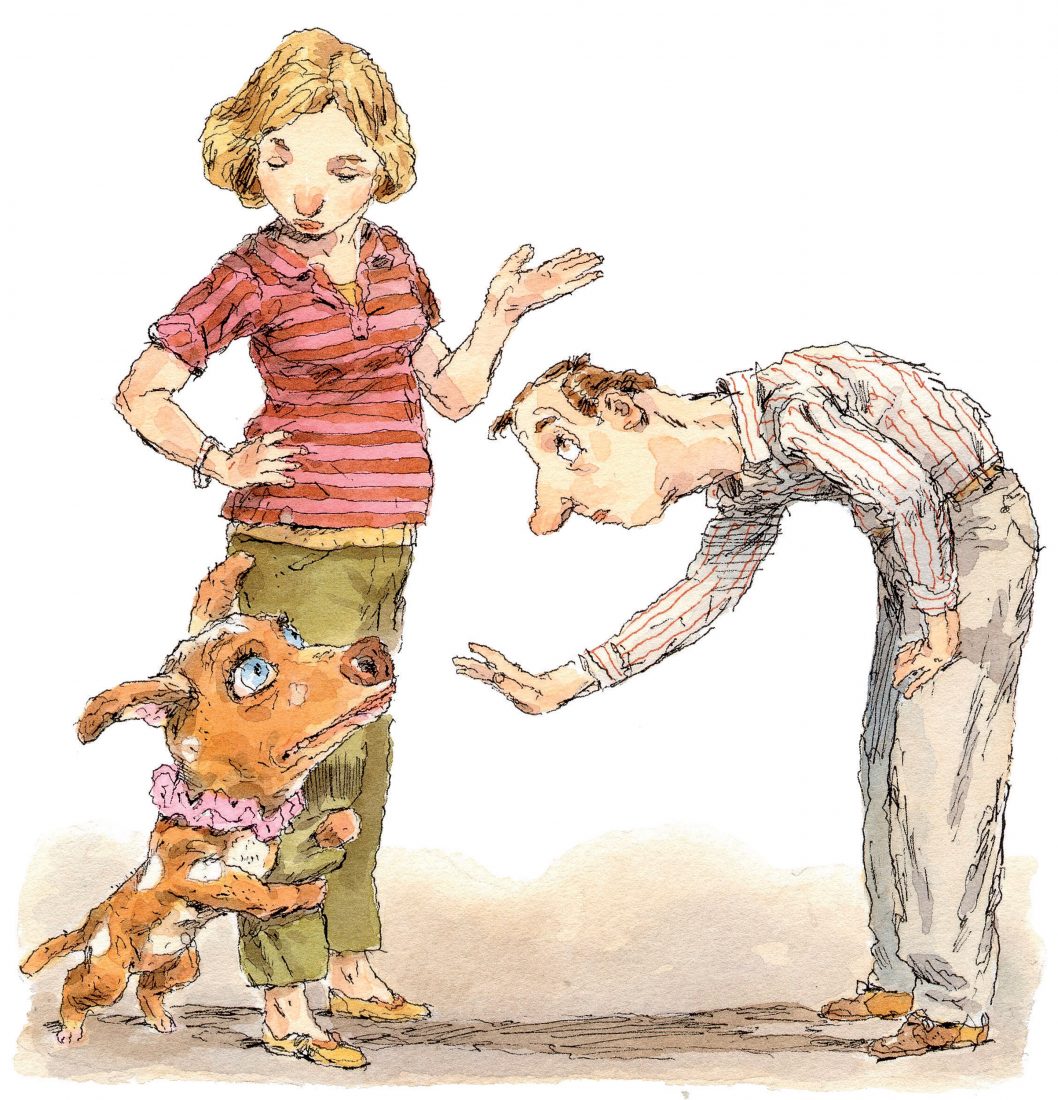

Playful at times, but with me, more often aloof, Rosie almost always turned and trotted the other way when I called her. She reserved her greatest spite, however, for men she didn’t know. When they came into the house, no matter how much they tried to ingratiate themselves with her, she would shrink behind Jessica’s legs and stay glued there until they left. This and the fact that she wouldn’t dare get on the couch, no matter how much we patted the cushions, made us think that she had been disciplined harshly by a man.

Rosie had a bushel of other quirks and qualms. Not surprisingly, she dreaded low-pressure systems and was better than a creaky knee for predicting storms, crouching at Jessica’s feet hours before the first rumble or raindrop. She craved her food, scratching at our bedroom door at dawn and ceaselessly begging an hour before her afternoon meal. If you approached her with medicine or a brush in hand, she’d slink away and hide. If you dropped something or made a sudden move with your arm, she’d skitter off in a flash, as if you were going to hit her. To this day, perhaps haunted by visions of the hurricane tide, she avoids any body of water bigger than the one in her bowl.

The girls soon found their way into Rosie’s heart. While Willa would forever be her first champion, Hazel taught her to sit, shake hands, and roll over. Nora became her groom, eventually coaxing her to sit still not only for brushing but for dog-and-daughter selfies. Once when Jessica was late getting home and Grace was worried, Rosie climbed the stairs, nosed open the door to Grace’s room, and reassuringly licked her tears away.

She positively hovered around Jessica. When Jessica went for a walk or got in her car, Rosie wanted to go with her. If I tried to take her for a ride, she ran to Jessica.

But with four children—and the kind that need hair braided and bows tied and other things I’m hopeless at—Jessica had her hands full. Dog rearing was on me. Besides, it was me, working at home, whom Rosie was stuck with most of the time. Despite her lingering fear of men, I set out to earn her trust and loyalty. Just letting her in and out and feeding her every day was a start. Rosie was so eager for her meals that she would dance in circles, joyfully rearing her head in front of me as I approached her bowl.

After breakfast Rosie took to going over to socialize with Coco and Stella, a black and a yellow Lab next door. Both yards have invisible fences. Coco and Stella don’t have travel passes, but Rosie does, through a system we developed together. At first, I would take Rosie’s collar off at the edge of the yard, holding it up to show it to her. She’d sit, raise a paw, and then I’d pick her up and carry her over the line. We did this for months. Now I take the collar off inside our house, show it to her, and then let her out my office door. She goes down the steps, looks back at me, and I clap twice. She runs halfway to the property line, looks back at me, and I clap again. She then runs to the edge of the yard and stops. When I clap one more time, she crosses the border. She usually returns on her own within the hour.

Rosie came with gimpy knees, which we took a wait-and-see approach on (that is, after a veterinary surgeon informed us she would need two operations with six weeks of total puppy immobilization for each, with a cost in the mid-four figures and only a fifty-fifty chance of success). She could run fast and play without any evidence of pain. She had no problem scurrying up our wooden staircase to scratch at our door in the morning but sometimes had a hard time going back down. She would sit at the top of the stairs, waiting, and I would carry her. I found this oddly endearing.

It didn’t take too long for our routines to boost Rosie’s comfort level with me. She found that she could hide behind me if a car backfired or a pesky kid was chasing her, and that if she wanted to play, I was the ticket. When we come home after a long trip, it’s my feet that she pees on. And the first time she ever ventured onto the furniture was after I had surgery to repair a ruptured biceps tendon. Still numb and doped up, I lay down on the couch with a ball game on. Rosie sidled in, nudged me with her nose, walked to the far end of the couch, jumped up, then slowly made her way up to cuddle with me.

Despite our rituals, Jessica remains Rosie’s favorite, something I have had to get used to. Even though I play with Rosie the most and feed her, it is to Jessica that she goes by default. One of my friends jokes that Jessica is Rosie’s master, and I am her bitch, and though that’s crass, in some ways it’s true.

I don’t mind, though. Rosie and I have come a long way together. We have a relationship that is both complex and symbiotic. Our days revolve around each other. We keep each other company. I counter her small betrayals with snarky nicknames, such as Pussy Cat, when she’s being scared; Snarfly, when she’s hoovering up crumbs in the kitchen; and Greg, the morning after another swan dive into our bed—all delivered sweetly, of course, so she doesn’t take offense.

We’re safe in our roles, and in knowing that, ultimately, we both answer to my wife.