It all began at breakfast in Franklin, Tennessee, when Tommy Peters asked if I would like to have dinner with B. B. King. Tommy had started B. B. King’s Blues Club in Memphis and was beginning to envision opening other clubs across the country. I had been in the music business for twenty-plus years, and he thought my connections would be beneficial. Of course, I said yes and asked when. “Tonight,” Tommy replied. Was B. B. King in Nashville? “No, we’ll be driving to Greenwood, Mississippi. We need to leave within an hour.”

Eight hours later, I was sitting at a four-top in Greenwood with Tommy, B. B., and Hank Aaron. Yeah, you read it right, Hank Aaron, a longtime friend of B. B.’s. And though I’ve never seen Mr. Aaron since, by the next night I was at Club Ebony in Indianola, Mississippi, watching B. B. onstage do what he did best.

Riley B. King was born on Berclair Plantation near Itta Bena, Mississippi, in 1925. He grew up in poverty and was left alone after his mother abandoned him and his grandmother died. He once told me that he would lie on his cot and listen to WLAC out of Nashville through the night. In those days WLAC spread the gospel of rhythm and blues widely as “the nighttime station for half the nation.”

There must have been a lot of passion brewing on that cot, for the guitar and the blues would pave B. B.’s way out of poverty and into a world he could have once only dreamed of. He was gifted with the ability to take the best of what had come before him, both as a stylist and a performer, and ratchet up a whole genre to a place it had never been. With “Lucille” in hand, B. B. became the King of the Blues while he comfortably blurred the lines between the blues and rock. He performed before presidents and at least one pope. Before he was finished, it seemed he had been inducted into just about every music hall of fame in existence.

Yet there was so much more to B. B., even beyond his role in the blues. I would grow to understand how wise and kind and fair he was in his dealings. He had a passion for the ladies, borne out by the fact that he fathered fifteen children. Beyond those fifteen were the other children of friends and family that he informally looked after over the years. He was passionate about life itself.

He was witty and curious and just downright decent. On a number of occasions, I got to see how he cared for his children, his more than sixty grandchildren and great-grandchildren, his fellow musicians, and his fans. Which leads me to a story that sums up so much of who B. B. was.

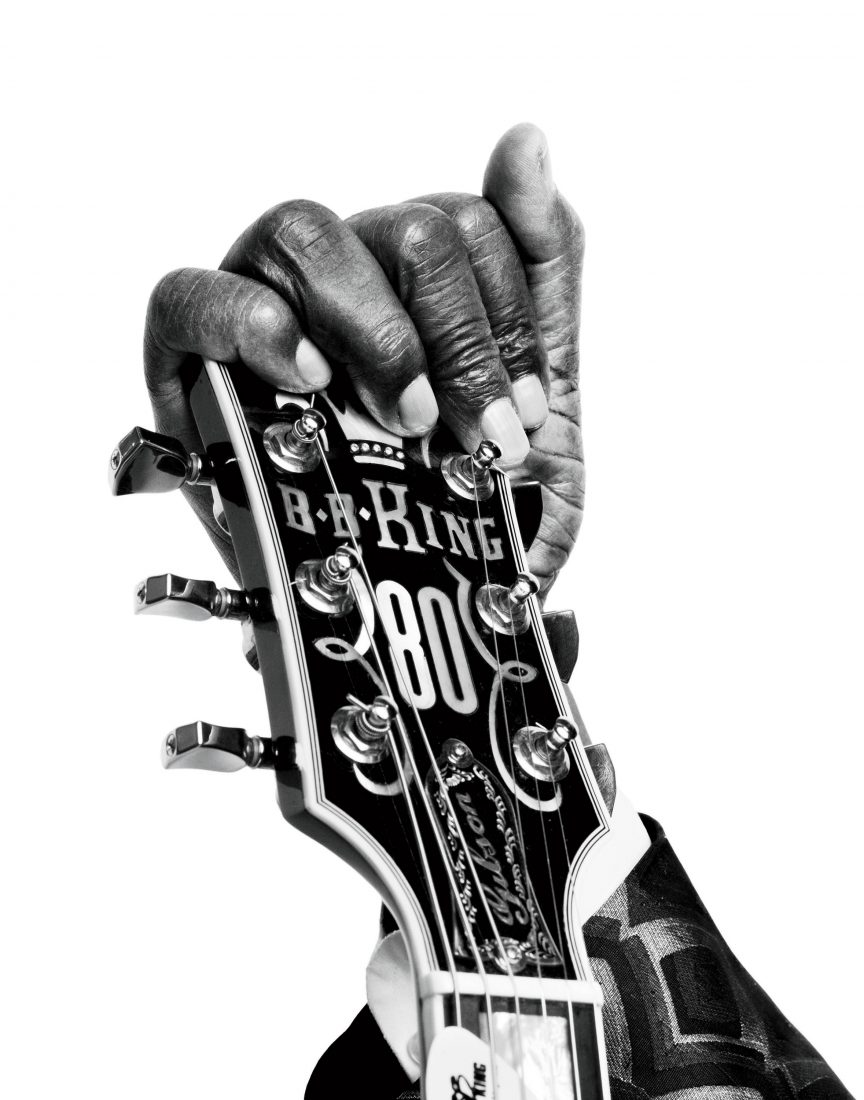

Photo: Mike McGregor/Contour by Getty Images

Gentle Giant

King photographed on tour in 2007

As it turned out, I got involved with those clubs that Tommy Peters had envisioned and by now had become Curator of Vibe, which is just about the best title any person has ever been given. I was charged with bringing together the particular visuals to ensure that the clubs felt more like music joints than chain restaurants.

We had opened a new club in Nashville, and B. B. came. Before his sold-out performance, he had a meet and greet with the local press. B. B. sat up onstage and fielded the questions. No matter where he traveled, by this point in his journey the press was pretty much made up of an adoring fan club.

In the midst of B. B. and the music writers laughing through their questions and his answers, an angry young man brought the room to silence when he reminded B. B. that several years earlier, he had said that when he began playing, his audience was close to 95 percent African American and 5 percent white, and now it was closer to 90 percent white and 10 percent African American. The young writer asked why this shift had happened and if it made B. B. as angry as it made him. Before B. B. could answer, the writer added that he saw it as nothing less than an appropriation and thievery of one group’s heritage by another.

Then B. B. quietly began to speak. He said that he would most likely never have known the blues if it hadn’t been for WLAC. But he wanted to say more, and all that decency and goodness that I had picked up on in the way he handled those around him began to ooze out. As if sharing a secret, one-on-one, with a disciple in the making, B. B. began to tell the young man that if truth be known, he would love to play for all the world, that he understood that men and women willingly gave over their hard-earned money to hear him, that he loved his audience without a thought of who they were.

And then he added, “It’s like that children’s song: ‘Red and yellow, black and white, they are precious in His sight.’ B. B. loves the little children of the world.”

I looked over at the young writer and his eyes had welled up with tears. “Don’t be ashamed to have asked the question,” B. B. said. “You needed to.”

That was B. B. King.