Two years ago, the intrepid food writer, journalist, novelist, poet, memoirist, and (whew) much-lauded humorist Calvin Trillin journeyed to my hometown of Greenville, Mississippi, to do a piece for the New Yorker on the second annual Delta Hot Tamale Festival. I’d implored him and he’d relented, but before he left, he tapped his notebook and said that if he managed to get a story out of what was inside, he’d nominate his own self for a MacArthur genius grant. He got one, of course (a piece, not the award, but he’s already won the Thurber Prize for American Humor), and it was terrific and funny and full of good stuff on tamales and Delta culture, both of which he’d long known a little bit about. During his stay in town, he’d gamely sampled fried tamales, vegetarian tamales, a tamale pie, and the rather more highbrow offerings of the competing celebrity chefs, including New Orleans’ Donald Link and Stephen Stryjewski, and Michael Hudman and Andy Ticer, who own three restaurants in Memphis. Then, on the day of the fest itself, a vendor offered him a more recent example of Delta food culture: a Kool-Aid pickle, also known as a Koolickle, a Day-Glo-colored delicacy made by draining the brine from a gallon jar of dill pickles and replacing it with double-strength Kool-Aid and a whole lot of sugar.

Trillin may well be the funniest human being I’ve ever met; he is also an exceptionally polite man. So after a couple of bites, when pressed for an opinion of the rather alarming cherry-red item in his hand, he “took refuge,” he wrote, “in the initialism I.C.P., Interesting Culinary Phenomenon.”

Clearly, Trillin was not mad for the Koolickle. And while I’m famously big on promoting Delta culture in all its glorious forms, I’m not entirely sold on it myself. But we are in the minority. As early as 2007, John T. Edge, the director of the Southern Foodways Alliance and a fellow Garden & Gun contributor, wrote in the New York Times that the popularity of the Koolickle had spread beyond the Delta—where it was mostly sold out of people’s kitchens (much like hot tamales), at neighborhood stores, and at blues-festival food stands—to cities as far away as Dallas and St. Louis. He also reported that the Indianola, Mississippi–based convenience-store chain DoubleQuick had applied for a trademark on the term Koolickle, coined by the stores’ director of food service. Since then, the application seems to have lapsed, and some DoubleQuicks now tout the same product under the name Pickoolas. Either way, to quote Edge, “Depending on your palate and perspective, they are either the worst thing to happen to pickles since plastic brining barrels or a brave new taste sensation to be celebrated.”

The latter is a happy fate that has greeted more than one I.C.P. I’ll have to ask Trillin, but I feel like when an I.C.P. becomes so entrenched that chefs start riffing on it with “gourmet” versions, it no longer qualifies for the initials. At any rate, it was bound to happen. Hayden Hall, a caterer in Clarksdale, Mississippi, who also owns the popular lunch spot Oxbow, made an upscale version of the Koolickle for some members of the Association of Food Journalists last fall that by all reports was a big hit. Hall has chops—he worked at Wolfgang Puck’s the Source in Washington, D.C., and Susan Spicer’s Bayona in New Orleans before returning home to the Delta—and he emphasizes the Koolickle’s sweet-and-sour flavor combo rather than its scary color, which he avoids by not actually using Kool-Aid. Instead, he heats up homemade lemonade and adds his own homemade dills along with a handful of rosemary or mint or basil from his garden, and lets everything steep before chilling. The formula, he says, keeps the pickle “in the ‘ade’ world” without being too outré. Next he’s thinking of adding vodka to the mix, an excellent idea that will take the pickles firmly out of the I.C.P. camp and turn them into convenient alcohol delivery systems along the lines of the now-classic vodka-spiked watermelon.

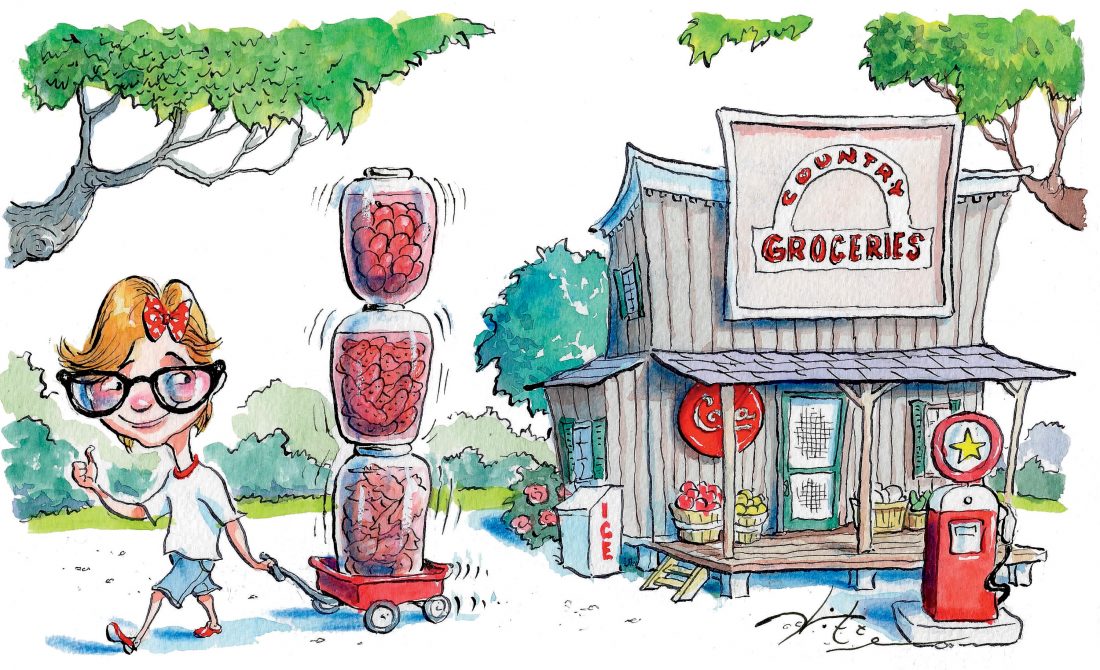

When I was a kid, dill pickles were just dill pickles and sat among the more bizarre or just plain gross items lined up in gallon jars on the wooden counters of gas stations and grocery stores—things like pickled eggs and pickled pigs’ feet and lips and hocks, as well as the occasional pickled sausages called Red Hots that are dyed the same scary red shade as the Koolickles of today. But just as Hall has fancified the Kool-Aid pickle, the whole nose-to-tail movement—the wildly popular trend in which chefs allow no part of an animal to go to waste—has moved the pig parts out of the gas-station jar and onto the upscale plate.

In 2006, Hudman and Ticer got turned on to nose-to-tail cooking when they spent a year in Italy prior to opening the first of their three restaurants, Andrew Michael, and attended a family pig killing. They remember the uncle procuring the brains to scramble up with some eggs while the grandmother, in her bedroom slippers, stirred the blood to keep it from coagulating. “We figured we could do the same in our kitchen,” Ticer says, and they did. The menu at Andrew Michael has featured cakes made of the meat of braised trotters (otherwise known as feet) as well as a localized homage to Raymond Blanc’s trotter stuffed with morels and sweetbreads (but because they’re Memphis boys and not a French chef camped out in England, the sweetbreads were barbecued first). Across the street at Hog & Hominy, they serve a pig’s tail that’s braised, fried, and sauced in the manner of buffalo chicken wings.

Now, nine years after their Italian foray, the duo’s latest venture, Porcellino’s, boasts a full-time butcher and meat curer, Aaron Winters, and a nine-hundred-square-foot-plus walk-in refrigerator containing whole carcasses of cows, lambs, and pigs, very little of which goes unused. Fried bits of pig ear lend some tasty crunch to the popular brussels sprouts salad, and smoked ears are turned into the occasional terrine. Now that they are finally happy with the texture of the pickled ears, they plan on frying them in strips and serving them in a mason jar along with some ranch dressing enlivened by Calabrian chiles, tarragon, and basil. “It’ll be sort of like a serving of fries with ketchup,” Hudman says, adding that if you cut the ears into long enough strips, “they’ll curl up a bit—they’re really pretty.”

Though the beauty of the slightly curled length of pig ear might elude a lot of people, those same folks will most likely be tempted by the ranch dressing, the sauce of choice for all manner of fried stuff, including the tamale. Likewise, the ears, says Hudman, will serve as “a vehicle to get ranch to your face.” Porcellino’s already has a similar vehicle on the menu, sliced pickled tomatillos, fried and served with an especially addictive ranch made with mascarpone cheese. That dish is an inspired tribute to a former I.C.P., the fried dill pickle chip, an item that long ago made the transition to I.D.P., or Insanely Delicious Phenomenon. (Hudman, who says he’ll “mow down a basket of fried pickle chips in a second,” agrees with my initialism.)

The fried dill chip is said to have been invented sometime in the early 1970s in—where else?—the Delta, near Tunica, Mississippi, at the Hollywood Café. Opened in 1969 and immortalized in the Marc Cohn hit “Walking in Memphis,” the Hollywood fries its much-copied pickles in beer batter seasoned with cayenne pepper and chile powder, and I can attest that they’re worth traveling many miles to enjoy. The thinness of the chip is key, as is the chip itself—at Pickle’s restaurant in Seaside, Florida, they serve batter-fried dill spears, a grave error (though I do recommend the frozen margaritas).

Ticer and Hudman say they have no interest in doing a take on a pickled egg, especially not the red-dyed version, another countertop I.C.P. of old, but Emeril Lagasse has a recipe for pickled eggs and beets that no less an arbiter than Martha Stewart posted on her website. The adventurous Hall has boiled and steeped eggs in red wine for color, but no chef I talked to had any interest in spiffing up pickled pork lips or hocks, the fatty knuckles of the animal. For the real, unadulterated versions, you can head online to the Pickled Store if your neighborhood market or childhood gas station has, perhaps understandably, given up on them. The site offers up no fewer than eight varieties of pickled eggs and five of pigs’ feet, but also lips and hocks, put up for three generations by a company called Matt & Dana in Amite, Louisiana.

The site Pickled Store bills the lips as “one of the cornerstones of pickled pork products” and laments, with a seemingly straight face, that they’re “getting harder and harder to find.” Despite a marketing pitch that claims “the best thing about pig lips is that you can kiss ’em before you eat ’em,” neither Hudman nor Ticer nor Stryjewski, chef/owner at Cochon and Cochon Butcher, has any intention of going near them. Stryjewski says the lips, disconnected from the hog, colored a deep red or pink, and grinning out from the sides of the jar, are the one pork piece he wants nothing to do with. “They scare me.” But the thing about the varied taste buds of our ever-surprising fellow countrymen is that one man’s unnerving I.C.P. is another man’s beloved snack. Judging by the testimonials on Matt & Dana’s pickled lips page, the company might live to see another generation. “A sleeper,” Skip writes. “Really good, unexpected, and now a staple.” Mindy agrees, calling the lips “a very nice experience! Strong porky flavor and wonderful texture.” Susie from Arkansas is even more effusive: “I’d have to give these pig lips the loudest Woooooo, Pig! Sooie! call ever.” Still, to play it safe, the company might want to consider branching out into the brave new world of Kool-Aid pickles.