As a child, I really loved escargot. The dish (which takes the French—and much sexier—name for “edible land snail”) was part of the education in sophisticated dining I received by tagging along with my father on numerous trips to our nation’s capital. There was smoked salmon carved tableside and a proper Caesar salad likewise tossed at the old lobby-level restaurant of the Hay-Adams Hotel, where we always stayed. Most exciting, a block or so from the White House, there was escargo and steak frites at the original D.C. “power lunch” spot Sans Souci.

We dined in the now-demolished restaurant so often I became a whiz with the tongs and two-tined fork required to extract the snail from its shell. And the thing itself, drenched in garlicky, herby butter (which was at least half the point, after all), was a chewy pleasure that carried over well into adulthood. Further, the snail happens to be the mascot of my alma mater, the Madeira School. Our motto is FESTINA LENTE (make haste slowly) and the school cheer is “Go, Go, Escargots!” Snails and me were clearly meant to be.

Or at least that was the case until the early 1990s, when I moved into a place in the French Quarter and presided over a magical garden spread out over two courtyards. Snails are no longer my friends. And the thought of actually eating one is—pardon the (sort of) pun—completely off the table.

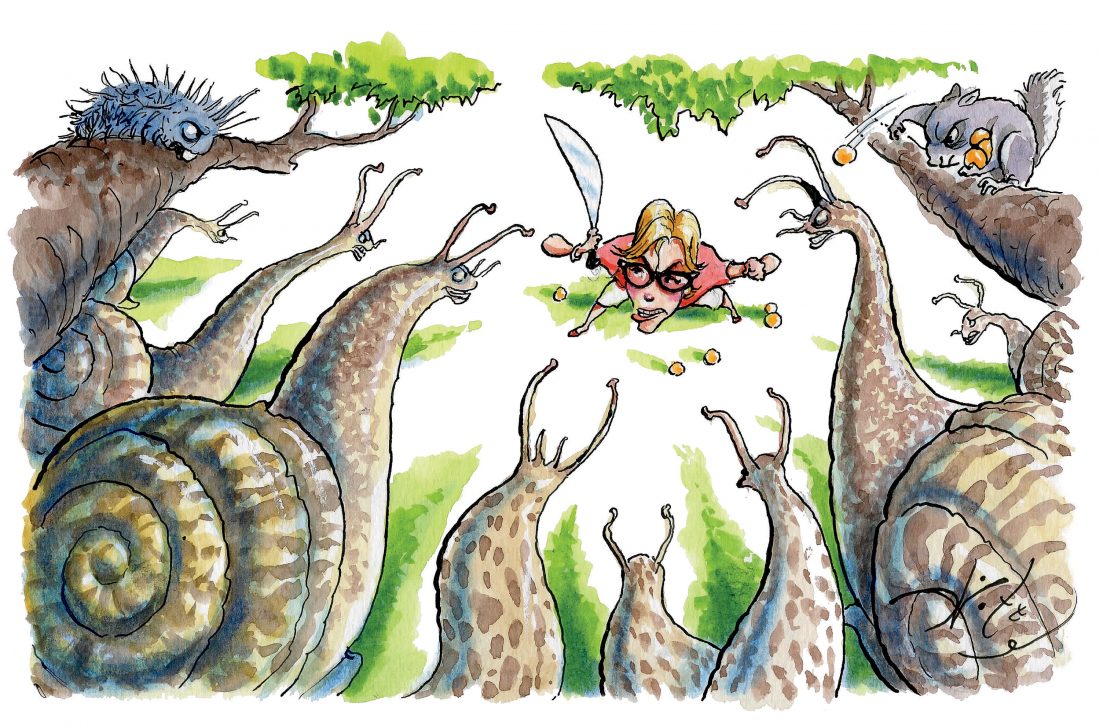

The tide began to turn early in my Bourbon Street tenure when I was awakened—at three in the morning—by the repeated sound of metal hitting brick. Terrified, I crept out onto the balcony and saw my landlady crouched over a bunch of slugs and snails she’d swept into a pile, wielding a huge machete. I thought she’d gone mad, but then I began to invest—heavily—in the garden and was driven to a similar point. The space was the perfect brown snail breeding ground. Walled on all sides, it was essentially a giant terrarium, full of the moisture the snails crave and possessed of endless spots for them to hide from the relentless daytime sun. It turned out that my landlady was not at all nuts (at least on this one subject); nighttime is the best time to catch them, and hacking them to bits is pretty much the only effective way to get rid of them.

The snails glided all over the place (and not all that damn slowly from the looks of things) on a muscular foot, leaving disgusting trails of slime and lacy holes in almost every herbaceous plant and all of my citrus. I tried bowls of beer and sprinkled the recommended coffee grounds and eggshells in the dirt to no avail. I bought hundreds of pounds of snail bait only to find their mucus all over the pellets, which never once impeded their targets. According to the website veggiegardener.com, “Crushing is the most common method of destruction.” Yep. But instead of a machete, I resorted to bricks, old shoes, a rusty shovel. And that’s the thing: Once you see a nasty pile of crushed snails in all their viscous glory, you figure out that the sauce you once enjoyed on similar mollusks would taste better on anything but. Then I read that the first step in preparing them as food is to purge them of “the likely undesirable contents of their digestive systems.” Case closed.

Even without the snails, gardening in New Orleans is not for the faint of heart. On Bourbon Street I had a monumental stand of banana trees that came with their own set of problems (such is the stickiness of their sap, you need a hazmat suit to trim them). When I moved to First Street, I planted a large live oak instead. It was beautiful, it grew like mad, its lovely curvy limbs shaded an equally lovely dining pergola. Which became a problem when I learned that buck moth caterpillars love oak trees as much as snails loved my courtyards. Covered in hollow spines attached to a poisonous sac, the caterpillars fell off the tree by the hundreds, creating a carpet of furry black land mines. This is not conducive to pleasant dining, nor is it conducive to a happy dog. Henry the beagle stepped on so many that in a single (mercifully short) season, he’d have to get as many as a half dozen cortisone shots.

There is a remedy for them, of course. And like most things in my former First Street garden, it required a hefty check to my trusty tree man, John Benton. I first interviewed Benton, the proprietor of Bayou Tree, for a story I wrote after a swarm of flying Formosan termites ate an entire beam of the Bourbon Street house in a single evening. When we put in the garden of the new house, he was my first call. Little did I know that he and his guys would also be the property’s most frequent visitors.

For one thing, even without the walls on all sides, the terrarium effect remained in full force. During the eight years we lived on First, I think there may have been one semi-hard freeze. The long “wall” of hollies I put in to screen my irritating neighbor’s house grew at such a rate we trimmed at least ten feet off the top every year. I spent whole weekends hacking ginger and trimming the seemingly endless tendrils of Confederate jasmine and fig vine. The upside was that the brand-new garden, designed by the brilliant Ben Page and divided into five “rooms,” looked as though it had been there forever. And Benton and I, by necessity, became fast friends. I advised him on affairs of the heart, recommended books, raged when he put the wrong grass in, adored him when he rid us of the caterpillars. Still, no matter how lush it looked as a whole, individual plants, like people, have minds of their own. On a field trip across Lake Pontchartrain, I bought a stunning variety of gardenias that made a fragrant hedge beneath the double parlor windows. Loaded with blossoms, the bushes grew so fast that Benton asked, “What have you been feeding those things? Chickens?” We laughed and marveled and laughed again. And then, not long afterward, they died. Every single one of them, for no apparent reason. We replaced them with cloudlike drifts of pittosporum, which ended up looking even more beautiful. Still, I was hurt. If gardens require courage, they also demand a thick skin.

Which leads me to the squirrels. Now, my mother has been in the gardening business a lot longer than I. Our Mississippi Delta yard was not much more than a field when we moved in more than fifty years ago, and now it most closely resembles a wildlife preserve. The last time I was home, Baltimore orioles were stealing the nectar from the dozens of hummingbird feeders. Two families of foxes live beneath various stands of magnolias. But the one form of wildlife my mother despises are squirrels: They eat the feed of her beloved birds and chew on the eaves of our house. She once persuaded the late sheriff of Washington County to send a half dozen deputies from his department to shoot them from our trees. I was aghast. My childhood copy of The Tale of Squirrel Nutkin is still stashed in my nightgown drawer, and I have always adored Dürer’s Two Squirrels, One Eating a Hazelnut, a print of which adorned my first cousin’s bedroom. When I was a young visitor at the aforementioned Hay-Adams, the angelic Filipino barman gave me bowls of peanuts to feed to the mostly gray squirrels in Lafayette Park. (This was a far kinder, gentler era, when it was safe for ten-year-olds to visit the park under the distant supervision of a hotel doorman and well before threats from the Libyans led to barricades along Pennsylvania Avenue.) Anyway, the squirrels would eat straight out of my hand and I remained their staunch defenders. Until now.

Having ditched the vast responsibilities of First Street three years ago, I figured my narrow apartment balcony, anchored by four large pots of citrus; a smattering of herbs, violets, and succulents; and the prolific night-blooming cereus that’s been with me since Bourbon Street, would be mostly maintenance free. And then the squirrels came. Leaping from electrical wires and the magnolia next door, they run brazenly along the wrought-iron railing, dive onto my satsuma and kumquat trees, and render them fruitless. Given my history with the peanuts, this is an almost literal case of biting the hand that feeds you. Though this is not the first time a fellow sentient being has betrayed my boundless love and trust, I’d rather come to expect such behavior from humans. From my furrier friends, it’s somehow a whole lot more upsetting. Squirrel Nutkin, indeed.

Want more Julia Reed? Her book South Toward Home is a collection of both rollicking and warm stories about the highs and lows of Southern life.