Born in Mississippi, Elizabeth Spencer, the author of nine novels and now eight short-story collections, published her first book in 1948. She has won many, very many, major writing awards, but more important, she is one of the greats, one who handles stories with grace and power—concisely, clearly. The writing never draws attention to itself. The story—not the “writing”—remains in memory. The reading experience is deep; no modern tap dancing here, only masterful, perfectly timed movement, with just the dither that signals command in art. And in this, Spencer locks arms with her former good friend, also from Mississippi, Eudora Welty. Welty openly admired Elizabeth Spencer’s stories.

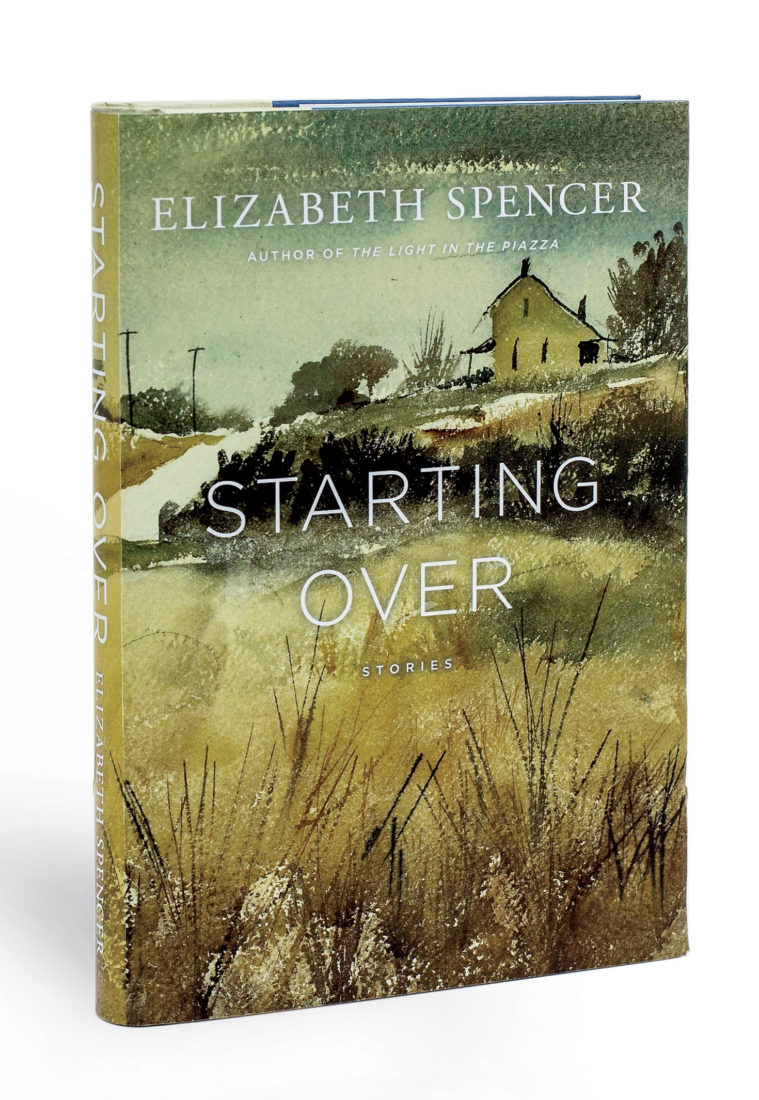

I’m glad I can respond to Spencer’s new collection of stories, Starting Over, like most human beings—just enjoy them as suspenseful, surprising reminders of how we live, how we relate to others and to ourselves. But since I also write stories, I will respond below first as a human being (A), then as a writer (B).

A. Elements of my Southern upbringing (and adulthood) run all through the stories in this book: religion, cousins, parenting, food, cousins, Christ-mas, neighborhood secrets, a dog, cousins, weddings, and funerals. Yet Spencer allows me to experience the hope and fear that reside beneath certain veneers and norms of Southern culture. I’m sure I’d be reading here about myself and my people if we were from, say, southern Sweden, or northern Spain.

B. In the opening story, “Return Trip,” a long-lost cousin, Edward, is coming to visit his cousin, Patricia, Patricia’s husband, Boyd, and their son, Mark. We learn that Patricia and Edward (whom Mark resembles) had a long-ago date. When Patricia returns from the airport after picking up Edward and taking him sightseeing, we read: “Later than it should have been, they pulled up to the cottage.” Many fiction writers would feel compelled to explain “Later than it should have been.” But Spencer has subtly maneuvered her point of view—later than it should have been to whom? Well, Boyd, the husband, of course. Spencer’s restraint and subtlety allow the reader to participate in the art.

In “The Boy in the Tree,” seven words better explain loneliness than hundreds or even thousands of words from some writers: “He’d no one to admit things to.

Another example of conciseness and power comes from the father/daughter story “Sightings.” We watch a reticent divorced man, Mason, and his daughter, Tabitha, prepare (with no coaxing of Tabitha by Mason) for a visit from Mason’s girlfriend: “She [Tabitha] ironed her jeans and put on some lipstick. She made a veal concoction, which was edible. Mason opened some wine.” Three sentences of mostly movement and nouns. No explanation, no analysis of how Tabitha feels about the upcoming visit. But we see that she is willing to welcome a potential stepmother. (And how many writers could refrain from naming the wine?) Tone, action, and nouns give us all we need. But in the same story, Spencer needs to get inside Mason’s head: “So they [Mason and his ex] would be back into it [a disagreement], Mason thought, and he saw the whole flawed fabric of human relations form, the present now becoming like the past, the future scrolling and looking just as always, torn, stained, blemished. No change. He winced.”

What a pleasure to not have to work at reading, seeing, hearing, knowing. To be a part of the art. You don’t have to be a writer to love these stories, but if you are, you will love them as you soak up how it’s done.