“A place that ever was lived in,” wrote Eudora Welty, closer to a hundred years ago now than not, “is like a fire that never goes out. It flares up, it smolders for a time, it is fanned or smothered by circumstance, but its being is intact, forever fluttering within it, the result of some original ignition. Sometimes it gives out glory, sometimes its little light must be sought out to be seen, small and tender as a candle flame, but as certain.”

No one, I think, would ever accuse Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium—celebrating its 125th anniversary this year—of being a quiet little candle of a place. The Mother Church of Country Music, which is to say, in many ways, American music, the Ryman radiates spirit and history. Surely, what began there so long ago now possesses Welty’s definition of inextinguishability.

From the beginning, it was made for the human voice. At a Nashville tent revival in 1885, the rough-and-tumble riverboat captain and Tennessee shipping magnate Thomas Ryman met the immovable object that was the preacher Sam Jones, one of the greatest orators of the day, who delivered the sermon that would bring Ryman to his knees and make him change his faithless ways.

With the zeal of the convert, Ryman reversed course and set about ridding his fleet of all liquor. Further, he declared that never again would Jones have to preach his sermons out in the cold and rain. Ryman contracted a prominent Nashville architect, Hugh Thompson, to design and build a church to caress and deliver, using only natural acoustic principles, the preacher’s voice. One building, one man’s voice.

I think you can still feel it—his voice, his passions, and his ambitions—in the wood, if not quite hear its vibrations.

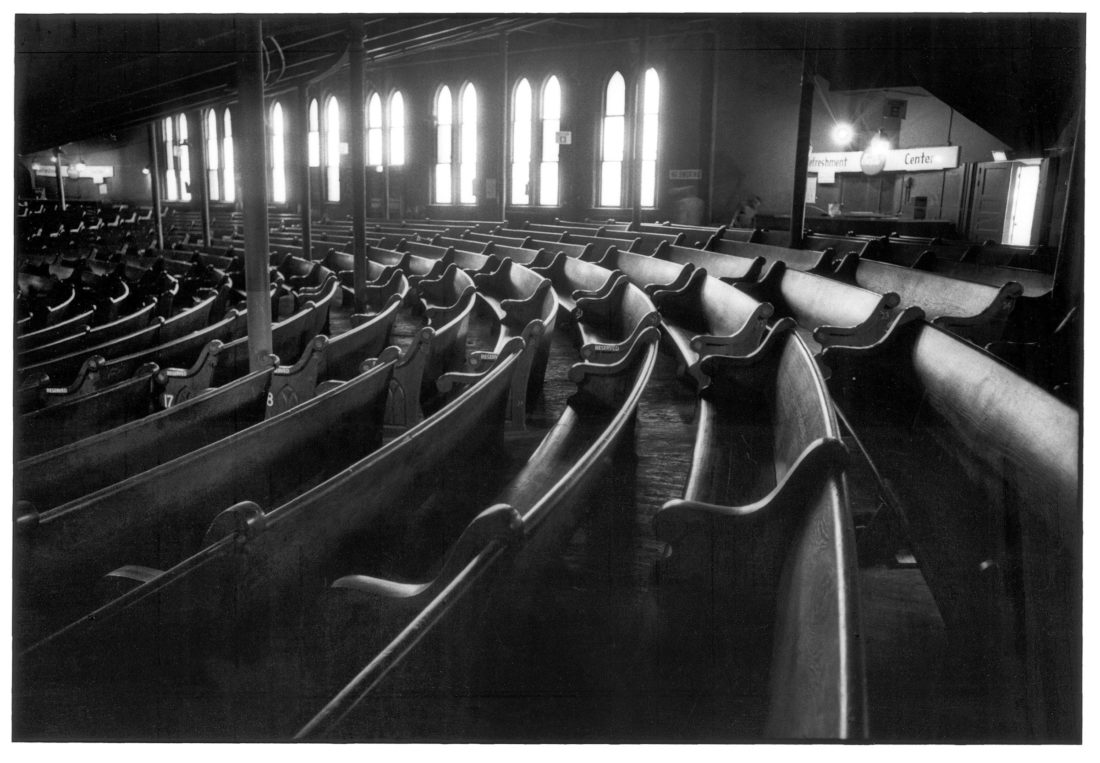

Photo: From the Jim McGuire Collection, Courtesy of the Grand Ole Opry LLC Archives

Sunlight filters into the Mother Church.

I have a sweet little dream. I have fallen in love with a small band I sometimes work with, named Stellarondo, after a character in Eudora Welty’s short story “Why I Live at the P.O.” They compose scores for me to read my stories to, and in so doing, I feel as much as hear their music. I have fallen in love with the way Bethany Joyce’s bow slides across the thick strings of her cello, and Caroline Keys’s delicate, delicious banjo plucking, and Jeff Turman’s moody and complicated bass, and especially Gibson Hartwell’s pedal steel. I do not think it is coincidental that our ability to hear is fully formed at birth—even in the womb, babies respond to the patterns of their mother’s voice or the melody of a “favorite” song.

The body knows this and loves it. Music heals, music builds. The architect Hugh Thompson knew this. The great Sam Jones knew it. And when the riverboat captain Thomas Ry-

man, in the greedsome perfidy of his time, felt his soul being saved—when he felt himself being rescued—he knew this, too.

My dream is this: I want to walk across those old boards, the stage creaking slightly underfoot, and read a story in that church, with that band, my band, making music from the throats of their instruments, and the chambers of their brains, heated briefly here in the condition of life, which is not a dream, but real—as real as the rasp of a plane on new-cut wood, the rip of a saw cleaving bright lumber, the hammer of a mallet, a church being built, and waiting for all who would ever enter, and speak, and sing.

My hearing has been damaged by a lifetime of chain saws, shotguns, and loud music, but in the Ryman, such things don’t matter; one’s entire body is wrapped, wreathed, in the roll-around curve of those sound waves. You’ve never heard sound—not just music, but sound—travel the way it does in the Ryman. I don’t mean loudly, or distance-carried: I

mean its richness and clarity. There’s such a purity to it that you consider for the first time that sound might be more organic than previously considered, that it can live like an

animal, traveling sometimes where it wants, and in whatever manner it desires. Seeking out certain places, certain hearts.

But back to that sermon. While no written record of it exists, secondhand witnesses said it was pretty simple: Jones exhorted those in attendance to “quit your meanness.” (A message one might long for just as sharply today.) Ryman did just that, building the church out of gratitude, the flip side of greed and arrogance. As if all things begin together, conjoined in some deeper place, then separate, before forever seeking reunification, or at least harmony.

Others came, after Ryman and Jones. Church services gave way to general auditorium duties, tinged with progressivism. A woman named Lula Naff saw to that. Deep into the heart of early-twentieth-century Tennessee, she brought Charlie Chaplin, suffrage movement leaders, civil rights speakers. For over fifty years—1904–55—she was the iron fist of the Ryman, signing contracts as “L. C. Naff” so that the talent’s agents would not suspect they were negotiating with a woman.

It was a powerhouse of revolutionary compassion. The country thirsted for music more than ever—needed music—after the horrible war, and in 1925, an insurance company,

National Life, began sponsoring a radio program on WSM that became known as the Grand Ole Opry. The Opry, which moved to the Ryman in 1943 and stayed there for thirty-one years, brought the high lonesome sound of gospel vocals as well as that of the banjo—an instrument co-opted from Africa and played often masterfully by poor white Appalachian hill folk—and something in the American psyche cracked open. A community of yearning and heartache and loneliness and joy began to come together. Fiddle player Uncle Jimmy Thompson was the Opry’s first act. Earl Scruggs, Lester Flatt, Bill Monroe, followed, then Hank Williams, who was called back for six encores, still a record. Elvis and Johnny Cash, who met June Carter backstage, where he told her he would marry her someday, performed here, too.

Photo: From the Jim McGuire Collection, Courtesy of the Grand Ole Opry LLC Archives

Johnny and June harmonize on “Will the Circle Be Unbroken” in 1974.

There were spats. Cash—fittingly—was an outcast for a while. Some performers viewed themselves as more “country” than others, and probably were. Elvis bombed in his only appearance, in 1954—the venue wasn’t yet ready for rockabilly—but survived the snub.

The Opry still returns to play at the Ryman in November and December of each year, and for the rest of the year, acts of all stripes are welcomed. The Ryman prides itself on being a garden, nurturing all talent.

I have a theory, that no work is ever wasted. The Ryman’s builders constructed it with the full attention of their craft, believing fiercely that beauty matters. They did not know that we, or anyone, would be coming. They simply did their best. And it endures, prospers, still. Who knows what beauty will fill it, or the world, or any of us, yet?