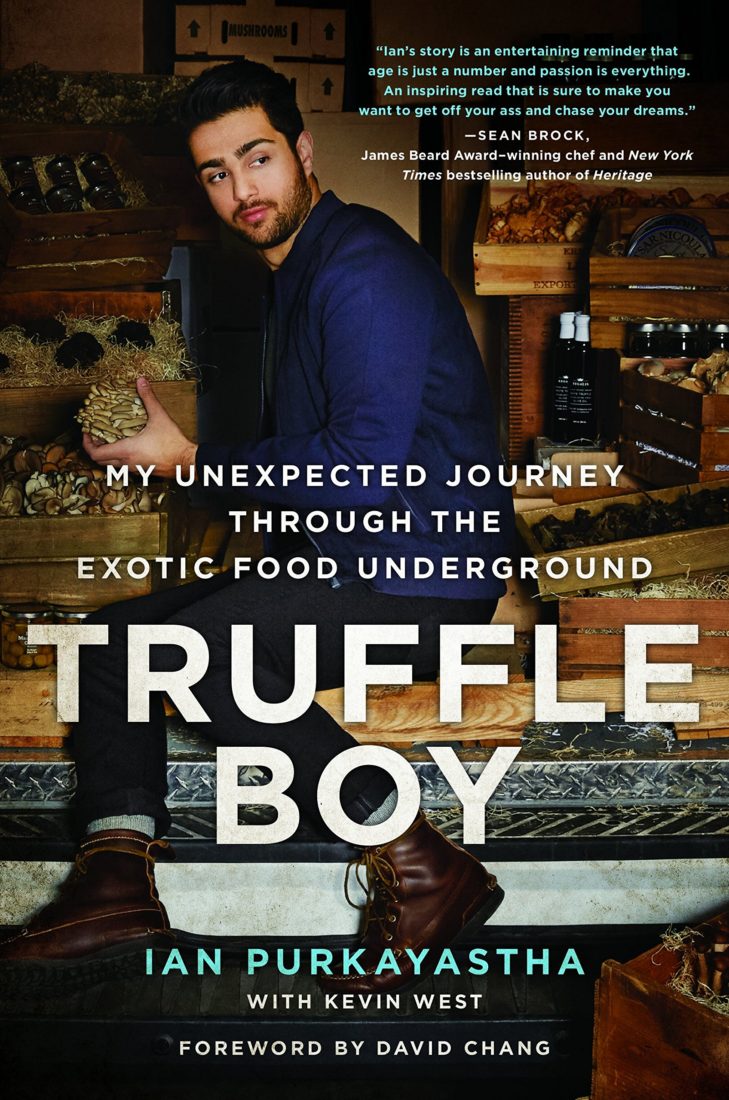

To have found your calling by age fourteen is already a pretty great gift. But for Ian Purkayastha, his zeal for one of the South’s oldest culinary traditions—foraging for wild plants and fungi—has also paid off.

As the Texas-born Purkayastha, now age twenty-four, relates in his new memoir, Truffle Boy, like many Southerners, he learned how to cook at the elbow of his grandfather. But it wasn’t until his family moved to Arkansas that a morning spent hunting morel mushrooms with his uncle sparked his obsession.

“I instinctively lifted them to my nose and inhaled the earthy aroma into my nostrils,” relates Purkayastha in the book, which was co-written by Kevin West. “It filled me with a degree of satisfaction that I had never experienced in school. Foraging was something I could do right.”

That interest led to a taste of a truffle at a Houston restaurant, and his love intensified. Soon, he was importing truffles from Italy and selling them to local restaurants—all before he graduated high school. A series of savvy moves later, Purkayastha has become the leading supplier of truffles and other coveted forageables to hundreds of the nation’s top restaurants and chefs, from David Chang to Sean Brock, through his New York–based Regalis Foods.

Part of Truffle Boy demystifies and “makes less stuffy,” says Purkayastha, the world of luxury food (one that can be sordid and sometimes dangerous—gun-toting Serbian truffle hunters, for instance). But Purkayastha’s enthusiasm rings most clearly when he’s writing about his time out in the field gathering wild plants and rarities, from the hills around his family’s home in Huntsville, Arkansas, to the forests of India.

If you’re itching to head out to the woods yourself, Purkayastha advises spring foragers in the South to try for the fungi that first captured his imagination—the distinctive morel (though if you have any doubts, consult a field guide before eating). “I look for ash trees, which have an almost honeycomb-shaped bark, like the morels themselves,” he says. “In the early spring, right after it starts warming up a little bit, I give it a week or two, then once we have a big rain, that’s when I go out and look for the morels—because they can grow almost entirely within a day or two.” Just be sure to slice them at the base when you harvest them, so that their root system stays intact. “If you pluck them out of the ground, they never come back,” he says.