Sporting

The Legend of Bo Whoop

More than sixty years ago, the South’s most famous shotgun went missing. Here’s the story of how it was found

Photo: Courtesy of Field & Stream

On December 1, 1948, two hunters emerged from the cool wetlands of Clarendon, Arkansas, and ambled along a country road. The men—Nash Buckingham and Clifford Green—had spent a long morning in a duck blind and were headed back to Green’s car, on their way home. Buckingham, then sixty-eight years old, was at the time one of the most famous writers in America, a sort of Mark Twain for the hunting set. At Green’s car, they met a warden, who asked to see their hunting licenses. The warden quickly realized that he was in the presence of the celebrated writer. He asked Buckingham if he could see the most famous shotgun in America, Buckingham’s talisman, an inanimate object that the writer had referred to—in loving, animistic terms—in a great number of his stories. The nine-pound, nine-ounce gun was a side-by-side 12-gauge Super Fox custom-made by the A. H. Fox Gun Company in Philadelphia.

The carbon steel plates on the frame were ornately engraved with a leafy scroll. The gun company’s signature fox, nose in the air, was engraved on the floorplate. The barrels had been bored by the renowned barrel maker Burt Becker and delivered 90 percent patterns of shot at 40 feet, an uncharacteristically tight load for a waterfowling shotgun. It was named Bo Whoop. A hunting buddy had designated it so, after the distinct deep, bellowing sound it made upon discharge.

The warden chatted up Buckingham, handling and admiring the writer’s gun, like a kid talking to Babe Ruth while holding the slugger’s bat. At some point during the conversation, the warden laid the gun down on the car’s back fender. Buckingham and Green soon bid the warden farewell and drove off, forgetting about Bo Whoop until many miles into their trip home. In a panic, they turned around and retraced their route, painstakingly eyeing every inch of the road, to no avail.

Buckingham spent the next few years in a desperate hunt for Bo Whoop. He lamented the loss of Bo Whoop in print, likening it to the death of a treasured hunting dog. He took out ads in local newspapers, offering rewards. He befriended local wardens and police, appealing to them to be on the lookout.

He would never find it. But in the process of its loss and failed recovery, its legend grew in stature. Bo Whoop became a metaphor for other things gone and never to be retrieved, like one’s youth or the American wilderness. It became the object of intense speculation and hearsay. Reports of Bo Whoop’s discovery surfaced regularly over the years. The gun was once supposedly displayed behind the counter in a southern Illinois pawnshop, only to disappear again, hastily, into the hands of a wealthy coal baron, before its identity could be verified. A man once fabricated a Super Fox, adhering to the specifications Buckingham had left behind in print, and sold it as Bo Whoop before being outed as a fraud. Bo Whoop became like the Russian duchess Anastasia, who purportedly died in the Bolshevik Revolution but kept turning up all over the world, different women claiming to be the youngest daughter of the last czar, still alive. Belief in the existence and reemergence of Bo Whoop required a great leap of faith. It became the province of dreamers.

The legend befitted its mythmaker. Theophilus Nash Buckingham was born in Memphis in 1880. He attended Harvard University in 1900, where his boxing coach was “Gentleman” Jim Corbett. There he contracted malaria and went home for a year to convalesce. When he recovered, he enrolled at the University of Tennessee, where he was the captain of the football team in 1902 (the team went 6-2). He pitched for the Memphis Chickasaws, a minor-league baseball team.

Buckingham was a man of idiosyncrasies. He was impeccably tidy in appearance, rarely seen in public without his tweed jacket and tie. He was a business owner, running a sporting goods store in the 1920s. Yet he never owned a house or a car, and never learned to drive. He was reportedly prone to moments of extreme forgetfulness, sometimes unable to recall the name of his own bird dog.

“Belief in the existence and reemergence of Bo Whoop required a great leap of faith. It became the province of dreamers”

Buckingham was also a strident conservationist. He covered conservation topics in the hundreds of pieces he penned for magazines like Field & Stream, Outdoor Life, and Sports Afield. He produced nine books (some were collections of his magazine stories), the most famous being De Shootinest Gent’Man & Other Tales, published in 1934 by the Derrydale Press. His writings sometimes veered into the pervasive sentimentality of that time, and some of his attempts at local dialect—particularly that of Southern blacks—are nearly indecipherable (he was no Twain in that regard). But Buckingham very often rose to the occasion in print, penning bons mots that must have induced knowing smiles and nods from his dedicated flock of readers. They loved him for lines like: “A duck call in the hands of the unskilled is conservation’s greatest asset.” They loved him for creating a legendary life for a shotgun.

In 1950 two considerate friends made Buckingham another Fox, named Bo Whoop II. But the original, in the mind of its erstwhile owner, would never be replaced. Buckingham died in 1971, two months shy of his ninety-first birthday.

Photo: Courtesy of James D. Julia, Inc., Auctioneers, Fairfield, ME

Bo Whoop's replica stock.

Photo: Courtesy of James D. Julia, Inc., Auctioneers, Fairfield, ME

The dedication on the gun's barrel

Lost & Found

Sometime in the 1950s a foreman at a sawmill in Savannah, Georgia, was offered an elegant but well-used Fox shotgun with a broken stock. The seller wanted $100. The Savannah foreman took one look at the fractured stock and countered with an offer of $50. The sale was made at that price. The foreman then put the gun in his closet, where it remained for the next three decades.

The foreman’s son, who also lived in Savannah, eventually inherited the gun upon his father’s death. He, too, left the gun in his closet, this time for nearly twenty years. But in 2005, for reasons unknown (the consignor’s family wishes to remain anonymous), he brought the gun to Darlington Gun Works, a South Carolina shop owned by Jim Kelly, a noted gunsmith. The foreman’s son wanted to repair the broken stock. Kelly, a student of hunting history, saw that on the top of the right barrel there was a hand stamp that read: “Made for Nash Buckingham.” On the top of the left barrel: “By Burt Becker Phila. PA.” Kelly was floored. “I couldn’t believe that this gun had walked right in here,” he says. He contacted a Fox historian to help verify what his own eyes had told him. The historian confirmed that this gun was indeed very likely Bo Whoop. Kelly told the foreman’s son what it was that he owned, trying to impress upon the man that the gun had significant historical importance. The foreman’s son seemed unmoved. He insisted on a replica stock, then took the repaired gun home.

Four years later, the foreman’s son fell ill. By that time he had passed the shotgun down to his son, the last of the three generations of a Savannah family that would own it for five decades. This man, in part to help defray medical costs for his sick father, decided it was time to sell it. He contacted James Julia, a personable sixty-three-year-old lifelong Mainer. Julia owns a leading auction house in Fairfield, Maine, that specializes in decorative glass and lamps, toy dolls, antiques and Americana, and, most famously, firearms.

In 2007 the James D. Julia Auction Company sold a shotgun nicknamed the Czar’s Parker for $287,500, the most expensive American shotgun in history. Parker had made the gun for Czar Nicholas II in 1914, but the gun was never delivered due to the czar’s unexpected execution at the hands of the Bolsheviks. In 2008 Julia sold the second-highest-earning American shotgun in history, an L. C. Smith 16-gauge with glittering gold barrel inlays that went for $235,750.

Julia was consigned Bo Whoop in late 2009. He knew he had something special, a shotgun that could perhaps approach his previous records. “But we had no idea how much potential this gun had until the word got out,” he says. News of Bo Whoop’s potential discovery burned up blogs on the Internet. “There was as much talk about this gun as anything I’ve auctioned in forty years in the business,” Julia says. When he displayed the shotgun at an antique firearms show in Las Vegas, a snaking line of people lined up all day, waiting patiently to look at, photograph, and hold the gun.

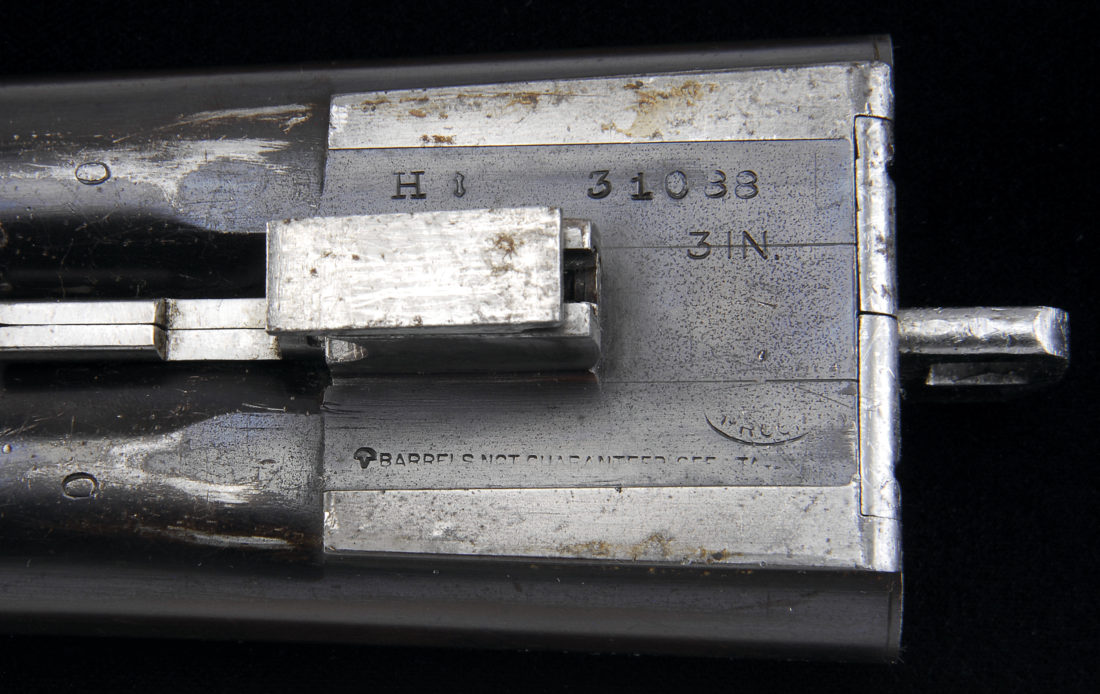

But a few sticky issues remained for Julia before he could sell it. One was verifying that the shotgun was indeed the real thing. Despite the hand stamps with Buckingham’s and Becker’s names, there was a problem with the serial number. Buckingham had once written in a letter that the number on Bo Whoop was 31108. But the serial number on the gun in Julia’s hands was 31088. Julia consulted a Fox archivist who said that the company did indeed have a gun with the former number, but that it was not from the Super Fox series that had been made for Buckingham. The latter number—the one in Julia’s possession—was the correct one for Buckingham’s gun, however. “I think it’s pretty obvious that Buckingham transposed a few numbers,” says Julia. It would not have been out of character for a man who was famously forgetful.

With that issue put to rest, Julia had an even more pressing problem: Who actually owned the gun? A lost or stolen item could very well be legally claimed by a family member. Julia says he spent months trying to get in touch with Buckingham’s daughter, who was believed to be still living. He never received a response. “We were in a touchy position,” Julia admits. Then he discovered that Buckingham had written in a book called Dear John—a collection of letters written to a hunting friend—that he had insurance on Bo Whoop. The story seemed to indicate that he’d been paid a settlement. “It was like manna from heaven,” Julia says.

What it meant was that the Buckingham family had no legal rights to the gun. Furthermore, Julia believes that the insurance company, if it still existed, would have only had claim to the money it had paid out, which Julia estimated would have been around $400, a sum he would have gladly paid back. Julia says he never tried to find the insurance company, but that it is “virtually impossible to have an ownership issue” for the gun. The matter was settled in his mind. Julia guaranteed ownership before the auction, which was to take place on March 15.

Photo: Courtesy of James D. Julia, Inc., Auctioneers, Fairfield, ME

The well-worn but intricate engraving on Bo Whoop.

Photo: Courtesy of James D. Julia, Inc., Auctioneers, Fairfield, ME

The well-worn but intricate engraving on Bo Whoop.

Bidding War

In early March, news of the impending auction caught the attention of an eighty-four-year-old man named Hal Howard, Jr., a former executive at T. Rowe Price. Howard, who speaks with the elegant accent of the Southern gentry, was born and raised in Memphis and still tends to his grandfather’s estate there, but he now lives in Palm Beach. He heard about the auction from his son-in-law in Vermont. “He saw it on e-mail,” Howard says. “And he told me it was happening in Maine of all places.”

Howard, as it turns out, had a vested interest in the shotgun: He was Buckingham’s godson. His father, Hal Howard, Sr., was not only Buckingham’s best friend and hunting partner, he was also the single most mentioned character in Buckingham’s stories. Howard, Sr., had died of a heart attack at age fifty-two when Junior was eight years old. Buckingham had penned a heartfelt elegy to the elder Howard, in a story called “Hail and Farewell.” The writer remained a presence in the younger Howard’s life until his death in 1971. “We hunted in Arkansas together,” says Howard, Jr. “And when my son was born, Nash stopped by and signed a book with a sentimental inscription and so forth.” Buckingham never talked about Bo Whoop with Howard (“I was around well after Bo Whoop’s time,” he says), but Howard immediately decided that he had to have the gun, to complete some cosmic circle.

Photo: Courtesy of James D. Julia, Inc., Auctioneers, Fairfield, ME

The gun’s serial number.

On the day of the auction, Howard had business to attend to, so he put a “younger cousin” in charge of the bidding, which was done by phone. “I told him to call me on my cell phone if the price got close to two hundred thousand dollars,” Howard says. He was determined to get the gun. “I didn’t want it to end up in Kansas City or somewhere where it had no relevance,” he says. The bidding on that day moved along quickly until it reached $100,000. Then the pace slowed as the field was narrowed to two people: One was Howard’s cousin, the other was a gun collector. The bidding went up in increments of $5,000 until Howard won it at $175,000. With the buyer’s premium, the final cost came to $201,250, the third-highest sum ever paid for an American shotgun.

Howard’s identity remained a mystery until April when it was announced that he was doing something wholly unexpected by the gun-collecting community: He was donating the gun to Ducks Unlimited (DU), a waterfowl conservation group in Memphis, in honor of his father’s relationship with Buckingham. To Howard, it was the perfect home for Bo Whoop. Howard had previously donated a diorama of Buckingham and his father’s camps, books, and journals that is displayed in DU’s front lobby. DU sits on property where Buckingham once hunted doves.

Howard, a hunter all of his life, has never fired the gun and never will. He has macular degeneration in his right eye, “and I don’t want to risk getting gunpowder in my left eye and going completely blind,” he says. He has stipulated that a few DU employees who are true Buckingham enthusiasts can shoot it before it goes on display. “I see this as an excellent completion of their memory and friendship,” Howard says.

And the fitting coda to a fable come true.