Sporting

The Wild Santee

Once the heart of Carolina rice country and the stomping ground of Archibald Rutledge, the tidal marshes of the Santee Delta constitute a natural treasure. Today, a handful of passionate duck hunters are helping to make sure it all stays that way.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

It’s hard to tell in the gray light of a cloudy dawn. I twist to shoot, but the birds are farther away than I thought—sixty yards, not forty—and the wigeon flare as I swing the shotgun. They peel off, wings frantic, a dozen ducks climbing over the old rice field, heading downwind toward the old levee, toward the tidal creek, toward the sea. I settle back onto the marsh seat and watch them turn into tiny flecks of pepper against the sky. I console myself for the blunder. It’s not only the monochromatic light that’s thrown off my bearings.

Here, where the land gives way grudgingly to the sea, it’s barely land at all, but a flat plain of half water, half marsh. The mosaic sprawls to the horizon, all the way to the South Carolina shore, and as far up the rivers as the tides exert their push and pull. Slave-built canals score the landscape for square mile after square mile. In every direction, slave-built levees draw straight lines across the horizon. The marsh where I hide was once a vast swamp forest, until it was drained and felled, plowed and diked, turned into a place of riches and misery, hope and despair, awash in such epic sweeps of human and natural history that fixing things in precise relation is a vexing calculus. In a landscape utterly transformed by man, where is the truly wild? And how far were those ducks? I press my face against the reeds, estimate the distance to the farthest decoy, and watch for the next flight to wheel in across the Santee Delta. It’s not much of a wait.

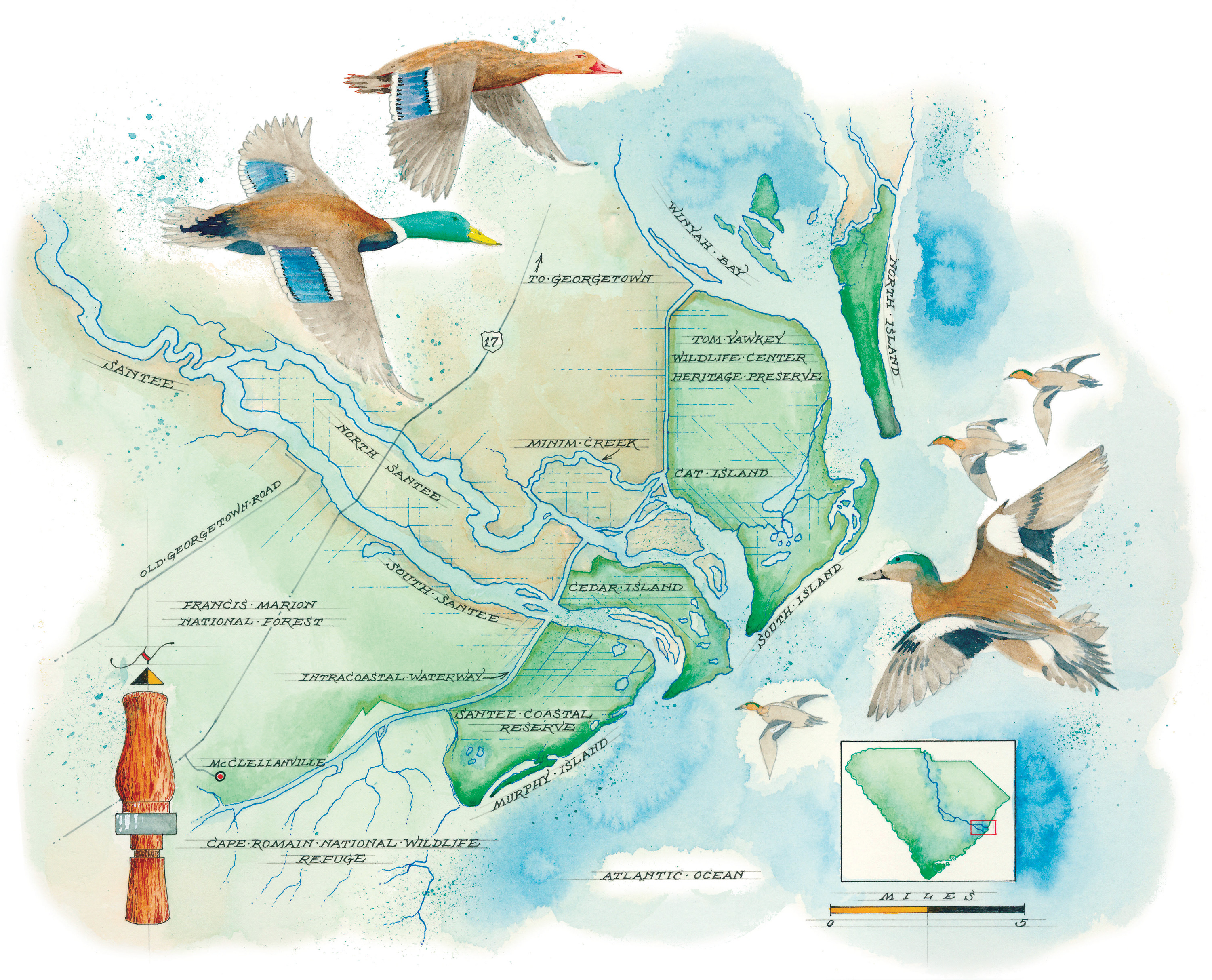

South Carolina’s Santee River Delta is a vast, little-known, and critical assemblage of conservation lands in the Lowcountry, a reliquary for rare landscapes and rare species, and a Serengeti for Southern ducks. The river itself drains the second-largest watershed east of the Mississippi River, its basin stretching from the South Carolina shore to the foothills of North Carolina. South of Georgetown, on the ocean side of U.S. 17, the river’s north and south branches unspool across a vast wedge-shaped expanse of tidal forest and marsh. It is the largest river delta on the Eastern Seaboard, part of a nearly half-million-acre cluster of public and private lands that reaches from the Francis Marion National Forest to Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge and the enormous state holdings at Santee Coastal Reserve and the Tom Yawkey Wildlife Center.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Southern Serengeti

Decoys in the morning light.

“Everything is here,” says Mike Prevost, a wildlife ecologist who works with forestry and conservation interests in the Delta. “We have endangered red-cockaded woodpeckers and sea turtles, huge flights of waterfowl and rare plants and enormous bird rookeries. We have one of the longest stretches of undeveloped coastline on the Atlantic. It’s a natural treasure, and it’s amazing how few people know about it.” Especially given the ducks that winter or migrate through the Delta each year. Waterfowling in South Carolina is always a roll of the weather forecast, but when it’s cold enough up north, the Delta fills with all eighteen of the state’s legal species of duck—blue-winged and green-winged teal by the tens of thousands, wigeon and gadwall, pintail, shovelers, and mallards.

Wild and unfettered as the Delta appears, however, much of it is an artifact of the South’s plantation past, and the result of human engineering on a transformative scale. By the early 1700s, maps were already showing the checkerboard rice fields dug into the Lowcountry. By 1776, Charleston was the richest city in the colonies, an empire built on rice.

While rice culture recast the Santee Delta, duck hunting, in large measure, saved it. As rice exports dwindled, wealthy Northern industrialists turned the old plantations into private duck-hunting estates, locking hundreds of thousands of acres behind their ivy-trellised gates. Today, those twentieth-century enclaves are a twenty-first-century beachhead against development. Some have been transferred to state or federal game agencies, others to conservation organizations. And many of the private properties that remain lead a vanguard of habitat conservation and management that pumps ducks into skies across the region, and shapes the Delta’s future as surely as rice shaped its past.

“That’s my great-great-grandmother over there in the azaleas.” Selden “Bud” Hill points casually to a hedge of bushes behind a trim brick church, barely breaking stride as we step through a gate into a cemetery and under tall pines. The ancestor he refers to is Eliza Henrietta Bacon, who married Hill’s great-great-grandfather Dr. William Thomas Wilkins Baker, who arrived in the Santee region in 1850 and served as a physician to Delta planters and slaves. “My people didn’t come over on the Mayflower,” Hill says wryly, “but we were in one of the rowboats not far behind.”

A photographer, historian, and founding director of the Village Museum in tiny McClellanville, Hill lives in the caretaker’s cottage beside one of the cultural totems of the Santee Delta, the Church of St. James-Santee Parish. Locals call the historic house of worship, built in 1768 by the Huguenots and Scotch-Irish, the Brick Church or Wambaw Church. It lies along the Old Georgetown Road, a white stone route known as King’s Highway 250 years ago, and the Great Catawba Trading Path before that.

The Huguenots were French Protestants exiled by the ruling Catholics in the late 1600s. The first of several waves of Huguenot refugees arrived in the Delta straight from France, settling in what was then a complete wilderness along the Santee River. These “French Santee,” as they came to be known, started with little more than axes and muskets, and soon began to transform the Delta.

Illustration: Mike Reagan

At the time, this chunk of the Lowcountry was predominantly wooded, with heavy forest all the way to the shore—early settlers described cypress swamp growing nearly to the ocean’s breaking waves. It was all cleared by slave labor for an agrarian system built on a clock maker’s level of detail. An eighty-acre rice operation required twelve miles of canals and drains, two and a quarter miles of dikes and banks, and the excavation of an estimated 117,000 wheelbarrow loads of muck and mud. Every backbreaking inch was dug by hand. “What happened here was on the scale of building the pyramids,” says Pierre Manigault, the chairman of Charleston-based Evening Post Industries (and one of the founders of Garden & Gun). Manigault’s ancestors emigrated from France to the Santee in the late seventeenth century. His great-grandfather Arthur Manigault bought the Charleston newspaper the Evening Post in 1895 and planted rice at the family’s Rochelle Plantation until 1907.

Which suggests just how entrenched the rice culture became in the Santee Delta. In 1849, a single South Carolina planter produced seventeen million pounds of rice. By 1860, writes Virginia Christian Beach in Rice & Ducks: The Surprising Convergence that Saved the Carolina Lowcountry, South Carolina produced 95 percent of the nation’s rice crop. In the Santee Delta, fifty-four rice operations blanketed the tidal lowlands. The industry imploded during and after the Civil War, and large-scale mechanized rice planting in Louisiana and Texas siphoned off any hopes of an early-twentieth-century recovery. But the old ways held fast in the soft muds of tidal Carolina. In the Village Museum, Hill tells me, there’s a photo of a rice barge at Hampton Plantation taken in 1925. “Everyone thinks the rice planting was over with the Civil War,” he says, “but people were stubborn here. The scale was reduced, but a few of them rode it out until they couldn’t ride it any longer.”

Swampy land, though, turns out to be good for more than growing rice. In the 1870s Northern hunters discovered the huge migratory flocks of ducks that pass through the old Carolina rice country, and a trickle soon turned into a steady flow of superwealthy bankers and industrialists who purchased massive expanses of the South Carolina Lowcountry. A dozen separate plantations were cobbled together to form the famed Santee Gun Club, which the Washington Post called in 1907 “probably the finest shooting preserves [sic] on the Atlantic Coast.” Monied New Yorkers hunted ducks in blinds so close to the coast they could hear crashing surf. In 1974 the old club was donated to the Nature Conservancy and now operates as the 24,000-acre Santee Coastal Reserve. In 2010, a $1.1 million renovation helped keep the clock turned back for a few more decades, and as I walked through the clubhouse, in the footsteps of frequent visitor President Grover Cleveland, I could see the nameplates of former club members still hanging in the wire-fronted gun safes. My tour guide laughed. “The gun safes were kept wide open, but each member’s liquor cabinet was locked,” she said. “That just tickles me.”

Scores of private hunt clubs took root in the former rice plantations. Many owners restored the old manors; others built their own. A few of those original families still own estates in the Delta, but most have attracted a new generation of owners, who are writing a new chapter in the intertwined history of ducks and land here.

From McClellanville and the Brick Church I wander back to Rochelle Plantation for a dinner thrown for a small group of Delta landowners and conservation organizations. Driving there on North Santee River Road, I pass a handful of plantation entrances, with meager glimpses of the large estates behind the live oaks and magnolias. Although this is a primary route into the heart of the Delta’s plantation region, fewer than a half dozen estates remain along the road. “It’s a small community of landowners,” Dan Ray says that night as we snack on quail eggs and venison sausage in Rochelle’s rare-book-lined dining room. “We’ve been successful in our business lives, and collectively, we want to be successful on behalf of the Delta.”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Bluebird Day

A hunter surveys the sky before calling it a morning.

An investment banker and Georgetown County native, Ray brings serious conservation bona fides to the Delta; he’s on the board of Ducks Unlimited’s Wetlands America Trust and hosts Wounded Warrior hunts on his 3,400-acre Annandale Plantation. He and his wife, Linda, bought the historic property in 2003—once part of a larger estate, it has plantation roots as far back as 1791—and the day after the sale, they put the entire plantation under a conservation easement.

Today there are vast Santee Delta private holdings under conservation easement, from Rochelle and Annandale to Crow Hill and the Oaks. “What is so exciting to see here is the evolution of a like-minded trifecta between federal government, state government, and private landowners,” Ray says. “There’s a real sense of carrying your own weight here, and the understanding that what each of us does impacts our neighbors. And from the perspective of a passionate waterfowler, our neighbors could be in North Carolina or Maryland—or across the Mississippi Flyway.”

To understand what’s at stake, it helps to find an elevated perspective. One afternoon I ride over to a lookout tower on Minim Creek with Phil Wilkinson, at age eighty-two one of the Delta’s living icons. Listening to his stories makes me realize that the old Santee history is really the recent past. Wilkinson grew up on Hopsewee Plantation, on the north bank of the North Santee, in a grand house built before 1740. He learned to hunt and fish from a black woodsman named Ben Simmons, who was born on the day Lincoln was assassinated. Archibald Rutledge, South Carolina’s first poet laureate and a revered chronicler of Lowcountry sporting life, used to pick Wilkinson up as the young man hitchhiked into Georgetown. After he graduated from Auburn University in 1962 with a master’s in wildlife management, Wilkinson spent a career pioneering waterfowl management techniques at the enormous 20,000-acre complex of marsh and maritime forest owned by Tom Yawkey, owner of the Boston Red Sox. When Yawkey died, in 1976, he bequeathed the entire property to the state of South Carolina. Renamed the Tom Yawkey Wildlife Center Heritage Preserve, the complex of marsh and river, islands and uplands serves as a sort of northern gatekeeper to the Santee Delta.

I take the lookout’s steps slowly. Wilkinson has blue eyes, a strong hooked nose, and a shag of gray hair bristled around the edges of his camouflage hat. He’s recently had heart surgery, and I want to see the revealed landscape as he does, so I don’t want to get too far ahead. Step by step, the Delta reveals itself. At the first landing, we clear the tall cordgrass and marsh elder for a good view of the creek winding through the marsh. Another five steps and the rice ditches lattice the landscape. At the top of the tower it’s an ibis’s-eye view, marsh by the square mile, ribboned with green shrubs. To the east, the vernal humps of South Island breach the marshes of the state-owned Yawkey Center. Ducks are working a rice field over on Ray’s Annandale Plantation. The horizon is etched with the marshes of the Santee Coastal Reserve, where President Cleveland once hunted, and farther south, Cape Romain National Wildlife Refuge.

Standing there, the wind ruffling our collars, Wilkinson remembers giant cypress trees killed by saltwater intrusion. “They were our landmarks at night when we’d go to Cedar and Murphy Islands for turtle eggs. Better not try that these days,” he says, chuckling. He points out a hummock of trees in the marsh. “Tranquillity,” he says. “Rutledge stayed there on a duck hunt he wrote about. All that’s left is a chimney.”

He’s quiet for a moment, then points out the geometric forms of the rice dikes. He wants to make sure I understand the paradox surrounding us. “The West Africans brought over a one-thousand-year-old technology,” he says, “and within a few generations it changed the Delta forever. Now those same rice field systems give us the ability to manage vegetation cover and water levels with incredible precision.” From high above Minim Creek, it all comes together.

It could also all have fallen apart. Just north of the Delta, the great sprawl of South Carolina’s Grand Strand engulfs the state’s coastal lowlands; to the south, beyond the Santee Coastal Reserve and Cape Romain, lie the developed Sea Islands and the Charleston metropolitan area. It’s all beyond our view, another testament to the size and sweep of this remarkable world.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Motte gets a post-hunt rinse

The view from the tower brings back to mind another view I had of the Delta marshes just that morning. The circumstances were quite different. Well before dawn, Pierre Manigault and I paddled across a broad ditch, then hiked through a long finger of cattail marsh that pushed deep into the open waters of an ancient rice field. Unlike a lot of diked field duck hunting, there are few permanent blinds at Manigault’s Rochelle. Water levels change; natural foods shift around. Each morning’s hunt location is based on the previous day’s scouting report, and we had to figure out where we wanted to be, how we planned to get there, and what decoy spread would match the wind and water. We tossed decoys all around, leaving landing zones at twelve o’clock and three o’clock and six o’clock, not quite sure where the ducks might want to be. We built a pair of one-man blinds with heavy netting and pushed marsh seats into the reeds.

Once again, it wasn’t much of a wait. Well before legal shooting light, the ducks whistled overhead, black shapes against gray sky, fluttering into the decoys. They seemed to never stop: At legal shooting light there were dozens on the water, paddling through the decoys, whistling and quacking. Scores more moved into a cove behind us—wigeon, gadwall, and teal. I heard shooting from a rice field a half mile away, but Manigault had yet to rise, and as a guest, I wasn’t quite sure if there was some unspoken rule to hold my fire. I gripped the shotgun and waited.

And still the birds came, drifting down into the decoys like leaves from a tree. I was inside a whirlwind of birds—red-winged blackbirds by the hundreds, egrets, herons, terns, shorebirds, and ducks. Within a few minutes, I counted a hundred birds in range, falling, lighting, swimming. I looked up to see four of a kind at fifty feet, a quartet of wigeon with wings set, feet down, on a course that might drop them inside my waders.

Let’s get this over with, I thought. I rose in the cattails, fired three times, and tracked a pair of ducks tumbling into the decoys.

At the shotgun’s report the rice field erupted as ducks sprang for the sky, hundreds of ducks, in every direction, in a cannonade of wings that echoed over the water as one flock of flushing ducks sent another into the air. I watched the birds swirl up and over the rice field, turning downwind, tendrils of ducks streaming up and away, and I wondered how long I’d have to wait to ever see such a sight again.

“I couldn’t take it any longer,” I called over to Manigault, apologetically.

“No need to apologize,” he said, laughing. “It had to be done. I just couldn’t bring myself to break the spell.”