Home & Garden

Thomas Woltz: Wild By Design

Unlike many landscape architects, Thomas Woltz isn’t interested in imposing his will on nature. He’d rather let nature set the terms. In the process he’s turning heads and proving that ecology can be beautiful

Photo: Michael JN Bowles

Thomas Woltz is in a hurry. On a blustery afternoon beneath a sky of bruised clouds, the landscape architect bounds up a hill on a 133-acre estate west of Charlottesville, Virginia. His ankle-high Chelsea boots (dinner-party fashionable, red-dirt practical) churn through brittle pasture grass toward a “pinetum”—an arboretum of pines, Woltz explains as I stagger-step to keep up—that he and his firm, Nelson Byrd Woltz Landscape Architects, designed for the owner. This collection features conifers from around the world, but only those that grow at the 38th parallel, the local latitude.

At the top, we pause for two beats to admire atlas cedar native to Algeria and Japanese black pine. We pivot west and, for two beats more, absorb the pastoral view below: white Georgian Revival manor house winking from a grove of trees, barn, rolling meadows ringed by woodlands, and, in the distance, the saw-toothed silhouette of the Blue Ridge Mountains. We walk over to a circular metal map of the horizon perched on a post, like something you’d see at a national park. I crouch, sight across a steel nib poking up from the center, and identify one of the peaks by aligning it with a scale drawing etched on the map. Woltz, who devised the system, one of many ways he decodes nature, looks on admiringly. He’s bundled in a three-buttoned topcoat whose gray herringbone perfectly complements not only his purple tie but also the dash of gray at his temples. His entire ensemble, in fact, appears tailor-made for the overcast day, which heightens the impression that everything I’m seeing is part of Woltz’s master plan. Before I know it, he’s off again, crunching through the meadow grass to show me something else.

Photo: Michael JN Bowles

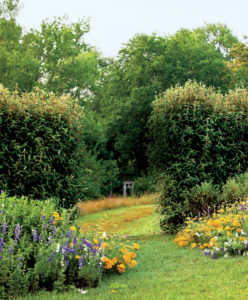

Nature meshes gently with the winding road and buildings at Seven Ponds.

Like other landscape architects, Woltz rearranges nature to reflect the hand of man. Unlike most, he redesigns farms—working farms—though his chief aim isn’t to pretty them up. Looks matter, but in his broader, more scientific view of aesthetics, beauty springs from the ecological health of the land. “This idea of decorating the outdoors is not what we do,” he explains.

Landscape architecture has its share of self-important designers who impose their singular vision on nature—who hate being considered glorified gardeners, wear their indifference to horticulture like a badge of honor, and don’t much care what plant you use as long as it can be sheared into a hedge or arranged in a geometric grid. Woltz isn’t one of those. At forty-five, with not quite two decades of client experience under his belt, he has emerged as a leader among a new breed of landscape architects who put as much stock in science as in art. He and his mentor and business partner, Warren Byrd, both Southerners raised to revere nature, exude passion not only for plants but also for the complex biological systems in which they thrive. “We design for ecological excellence,” Woltz says.

He has brought me here, to Seven Ponds Farm, to show me the birthplace, some fifteen years ago, of the Conservation Agriculture Studio, his name for the firm’s multifaceted program for designing “working land.” The ConAg approach differs from region to region, but generally, Woltz seeks to make farmland healthier and more productive and, as a result, more beautiful. As designer, he collaborates with three key partners: landowner, farmer, and a team of scientists, including conservation biologists, soil scientists, ornithologists, and others. Together, they do things like remediate silt-choked streams by building check dams and fencing out cattle; improve pasture through rotational grazing; and boost native wildlife by killing invasive trees and shrubs. Woltz is a big proponent of warm-season grass meadows, which don’t require fertilizers or machine mowing and harbor quail and buzz with diverse populations of pollinators. In terms of aesthetics, whether bursting with wildflowers or waxing brittle golden in winter, meadows look great in all seasons.

Woltz and his colleagues at Nelson Byrd Woltz apply the same principle to non-ag projects, such as city parks, corporate campuses, and memorials. The firm has exploded in growth, from two landscape architects in 1985 to thirty-five working out of offices in Charlottesville, New York, and, as of last fall, San Francisco. They’ve worked in twenty-five U.S. states and nine foreign countries, including New Zealand and China. In 2012, Woltz and team became lead landscape architects for one of the largest mixed-use projects to surface in urban America in decades, the redevelopment of midtown Manhattan’s twenty-six-acre Hudson Yards.

Photo: Michael JN Bowles

Hand of Nature

Woltz, who divides his time between New York and Virginia, works in his Charlottesville office.

Exciting as that commission is, in terms of impact, Woltz’s farm work may be more significant—and ambitious. The roughly 15,000 acres his ConAg Studio has touched so far are impressive from a landscape architecture standpoint but a drop in the bucket when measured against the 2.5 billion acres of U.S. farmland, much of it drenched in chemicals and worked by diesel-powered machines. Woltz knows that changing conventional wisdom about landscape architecture and farming is a tall order. Which may be why he’s in such a hurry.

Woltz and Byrd each witnessed the forests, farms, and streams of their childhood bulldozed by developers, a fact I learn during my visit to the firm’s Charlottesville offices, located in a rambling nineteenth-century brick house in the historic courthouse district. I find Byrd at the top of several creaky flights of stairs in a garret office known as the Byrd’s Nest. Now sixty years old and easing into retirement after officially turning over the reins to Woltz in 2011, he wears a wrinkled cotton shirt, untucked. He swivels away from his computer screen to help me connect the dots between past and present.

Photo: Michael JN Bowles

An elliptical pecan orchard follows the lines of a former riding ring at Seven Ponds.

Byrd grew up in northern Virginia, where creek-bed explorations shaped him into an amateur naturalist. But after the construction of Interstate 66 and the Washington Metro’s western commuter line, one Fairfax County farm after another gave way to subdivisions as the county’s population shot from 100,000 to 1.2 million.“Pastures were being torn up, and streams were being buried,” he says. In choosing the field of landscape architecture, he asked himself, “Can I repair what was lost during my childhood, particularly the creeks and streams?”

Byrd joined the University of Virginia faculty in 1979 and opened his ecology-minded practice a few years later with his wife, landscape architect Susan Nelson. As an educator, Byrd says, “one of the critical things I did was to get students into the field. I wanted to teach why a plant grows where it grows, what plants associate with it. That’s how you learn, by observing nature, not just abstractly studying it out of a book.” One of those students was Thomas Woltz.

Woltz knew from a young age that he would become an architect. But it wasn’t until years later that he added “landscape” to the job description. The youngest of five children, he was born in 1967 and raised on a cattle and crop farm in Mount Airy, North Carolina, at the foot of the Blue Ridge, where his father owned Quality Mills, a maker of upscale knitwear. Though financially comfortable, the family, according to Woltz, worked hard to grow their own food, sprouting flats of seeds in the dining room each spring, cultivating terraced garden beds out back, and sweating over steaming canning pots in August.

Like Byrd, the young Woltz felt the loss of rural land like a punch in the gut. Suburban sprawl wasn’t a threat in sleepy Mount Airy, but Woltz learned early on that farmland is always at risk. During visits to his mother’s family in Haywood County, near Asheville, they passed Springdale Country Club, whose fairways and greens had been carved out of a farm that once belonged to his mother’s family. Part of a colonial land grant, the land had been passed down for two hundred years, until the Great Depression, when Thomas’s grandfather sold it to avoid financial calamity. During the 1970s, when Thomas was still a boy, his father’s family developed its Mount Airy farm into the Cross Creek Country Club.

After high school, Woltz studied architecture at UVA, still dreaming of designing buildings. After graduating, he marched on, moving to Italy to run UVA’s summer program for architecture students. He stayed for five years, practicing with a Venetian architecture firm during the off-season. Ironically, it was in Venice, a flooded city essentially devoid of plants, that the idea of designing landscapes first occurred to him.

“Growing up on a cattle farm, I thought landscape meant pastures, meadows, and forests,” Woltz says. “In Venice, there’s only water and pavement, but it’s all so beautifully designed that, in terms of the spatial constructs, you feel the satisfaction you get from living landscapes.” He realized that his true calling was designing at the intersection of man and nature—of culture and agriculture.

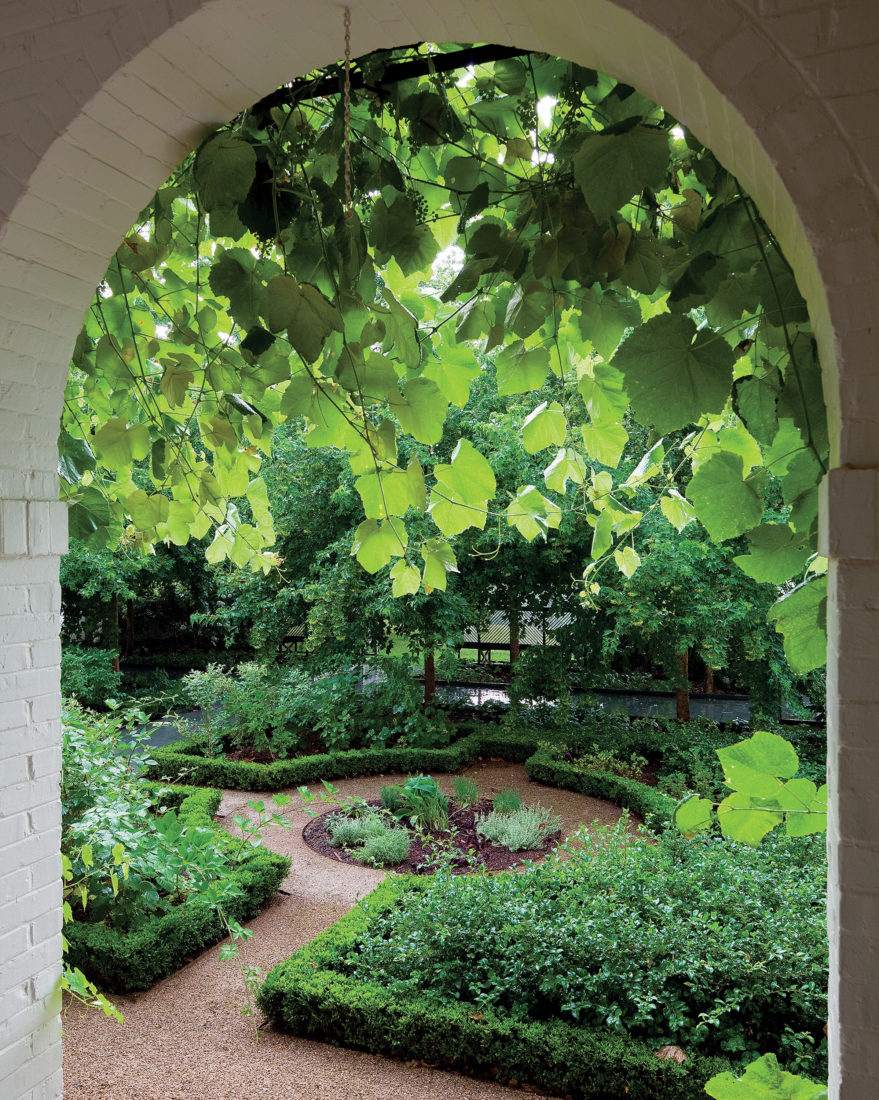

Photo: Michael JN Bowles

An herb garden near the kitchen.

“With buildings you’re often in apology mode,” he explains, “as in, this is the least damaging building, the materials came from the least distance away, the footprint is the smallest we could possibly build. But in landscape architecture it’s all about abundance—of wildlife, trees, flowers, fall color. Every piece of the discourse is about rebuilding and adding and extravagant abundance. The scale of impact one can have as a landscape architect who, in his heart, is committed to conservation and improving the world we live in is really appealing.”

Woltz left Italy and enrolled in UVA’s landscape architecture graduate program, where, as a student in Warren Byrd’s Plants and the Environment course, Woltz recalls, he slogged through swamps, “learning about plants—bald cypress, wax myrtle, coastal azaleas—in the context in which they naturally occur.” Woltz caught the plant bug and signed up for as many of Byrd’s classes as possible. When he graduated, Byrd hired him. In 2004, he became a partner in the firm, and, in 2011, he bought Byrd out to become sole proprietor.

Woltz steers his weather-beaten, early-model Volvo sedan through the gates at Seven Ponds, narrating his ConAg Studio master plan as he drives. “We lined the entry with native cedar to hold off the view,” he says, as we pass through a dark grove of green. The twin rows of cedars end, and, as intended, a feast of golden grasses, mountains, and farm buildings unveils itself before my eyes.

“There,” he says, pointing to the intersection of forest and meadow. “We groomed the border to look like an advancing mesic forest.” The different species—oaks, maples, persimmon, vibernum, witch hazel—grow shorter the closer they are to the meadow. If I didn’t know better, I’d think it was a natural forest in the process of successional change. “We get ecologies rolling,” Woltz says.

Photo: Michael JN Bowles

Edge of the Life

The driveway at Seven Ponds is lined with Asian pear.

Lots of people assume that being a good steward means leaving their land alone. But that approach doesn’t work anymore, Woltz says, due to the postwar explosion of exotic invasive species—not just the well-known culprits, like kudzu and mimosa trees, but also Russian olive, Japanese barberry, burning bush, and other devastating garden-center favorites. “If you don’t know plants well, you might think you have healthy forest,” he says. “We don’t have the luxury anymore to not engage in some kind of management of our lands.” Much native wildlife hasn’t adapted to eat foreign seeds and leaves. Therefore, killing invasives allows native plants to thrive, which, in turn, boosts populations of insect pollinators, birds, amphibians, and mammals. “What we’re really farming,” Woltz says, “is biodiversity.”

At Seven Ponds, that’s literally true, because the owners are not running a commercial farm. During the past fifteen years, they’ve turned a worn-out cattle farm into a residential estate with a small pecan grove, orchard, and vegetable garden. With its white neoclassical home, it’s like a Virginia horse country version of Renaissance Italy. Most of Woltz’s other ConAg clients do run businesses, including grass-fed beef, organic vegetable farms, and a former winery now making gourmet grape juice. The designer readily admits that his agricultural clients, like most people who hire landscape architects, are wealthy—and not from farm income. Just because they’re investment bankers or doctors doesn’t mean they’re not committed to the ConAg model, but it does limit the program’s reach.

Woltz is working on a solution. He and his cadre of scientists are collecting and analyzing data and plan to share the findings. “The goal is to get it into the hands of farmers who can’t afford a conservation biologist or landscape architect,” says Woltz, who hopes to tap existing channels of information, like county cooperative extensions. “I’ll admit the scale is small, but one day, when the government says we’ve got to stop dumping chemicals into our watersheds or genetically modifying food and looks around for who’s farming in a sustainable way, I hope we can offer up hundreds of examples.”

“I didn’t know what to expect when I heard we were going to work with a landscape architect,” says Phillip Ponton, the longtime vineyard manager of Oakencroft Farm, a Charlottesville vineyard and grass-fed beef operation. At Oakencroft, Woltz organized a “bio-blitz,” bringing a team of seventeen university field scientists to take an ecological snapshot of the place. For three days, they surveyed mammal, bird, reptile, and fish populations, catalogued plants, and sampled soil. “Since then, we’ve changed our farming practices,” Ponton says. “We’ve fenced off streams, paid more attention to cattle rotation, fought invasives, planted insectaries to increase the number of pollinators. In a few years, we hope to take another snapshot.” When they do, they can measure their ecological progress against the baseline that the first bio-blitz established. “It’s been a pleasure working with Thomas,” Ponton says. “A real eye-opener.”

Opening eyes is exactly what Woltz hopes to do. After noticing how Woltz’s team rejuvenated Seven Ponds’ spent farmland, a neighboring landowner, Kay Leigh Ferguson, hired him to design a master plan for her twenty-two acres. “I’m small fry for him, but he was interested because my property extends the corridor of native habitat at Seven Ponds,” says Ferguson, who enjoys working the fire breaks during seasonal burns in her warm-grass meadow. “He’s interested in these corridors. In terms of wildlife, corridors are more important than squares or circles.”

“One of the challenges for landscape architects is dealing with property lines,” says Charles Birnbaum, founder and president of the Washington, D.C.–based Cultural Landscape Foundation, which seeks to preserve historic landscapes, including farms. Woltz serves on the foundation’s board of directors. “I’ll never forget how excited Thomas was about two residential commissions in Kentucky that shared the same watershed. He saw a chance to work beyond individual property lines.” Nature is made up of complex interconnected systems, says Birnbaum, and “Thomas’s quest to understand these systems in all their dynamic dimensions underpins everything he does.”

Without exception, everyone I ask about Woltz describes him as “visionary,” a term that gets tossed around nearly as much as “innovative” or “sustainable.” But the more time I spend with Woltz, the more that seems like precisely the right word. “Landscape architecture is the best profession in the world, because I get to think at so many levels, from the tiniest detail of construction to the largest-scale geology,” he says. It’s about unearthing hidden connections, such as the way Precambrian granite extrusions link Georgia and Nova Scotia; how Blue Ridge farm streams impact the Chesapeake Bay; how healthy meadow grass boosts crop productivity; or how a farm’s ecological condition affects the health of those who inhabit it.

In making the switch from architecture to landscape architecture, a central question for Woltz was: “Are there ways that our landscape designs can connect people and teach people about these giant systems, whether it’s horticulture, geology, hydrology, or human culture?”

With every landscape he designs, Thomas Woltz emphatically answers: Yes.