This is a story about guitars—rare and odd and beautiful guitars, all of them important in Southern music history—but it begins with a fiddle.

Deke Dickerson was born and raised in rural Boone County, Missouri, but his paternal ancestors hail from Floyd, Virginia. There, in the late 1920s, his great grandfather ran the country store (the one now famous for the Friday Night Jamboree). One day in walked a slight man who told Mr. Dickerson that he would like to sell a fiddle. Mr. Dickerson, a music fan, recognized Charlie Poole right away. Poole was famous chiefly for two things: his distinctive banjo playing with the North Carolina Ramblers, and his thirst for booze. Poole left the store with enough money for a hefty ration of moonshine, and the Dickerson family took possession of what might have been an important piece of Southern music history.

Deke Dickerson inherited the heirloom as a teenager, by which time he had become well known in mid-Missouri as a guitar prodigy. “The fiddle took on a mythological aura in my family,” he says. “I heard it talked about in hushed tones my whole life.”

A local restorer of vintage musical instruments deflated the myth. “He looked at it and said, ‘This is the kind of fiddle you’d get out of a Sears catalogue,’” Dickerson recalls. “The punch line is that Charlie Poole probably just stole it from his band’s fiddle player so he could sell it for some hooch.”

Dickerson’s instinct to suss out the provenance and authenticity of a musical instrument is just one trait that makes him a great collector. Now living in Los Angeles and touring tirelessly with his band, the Ecco-Fonics, his road-tripping in his enormous gold Cadillac centers as much around hunting for guitars as it does around playing gigs.

In the twenty-six years since he met with the restorer, Dickerson has assembled a trove that could constitute the core inventory of a museum of Southern music. In fact, one fastidiously restored piece—the 1958 double-neck Harvey guitar Paul Buskirk played on the original recording of Willie Nelson’s “Night Life”—will go on display next year at Nashville’s Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum.

Dickerson’s collection includes more than a hundred guitars, but he won’t say exactly how many, in part to make the point that he’s more concerned with quality than quantity. Of course, quality is subjective. For Dickerson it means obscurity and quirkiness, and the guitars that require the greatest effort to obtain and authenticate give him the greatest pleasure.

Amy Dickerson

String Section

Deke Dickerson with seven of his prized instruments, including a 1958 Danelectro “guitarlin.”

Link Wray’s 1958 Danelectro longhorn “guitarlin” (a guitar/mandolin hybrid) falls into this category. Wray, a Shawnee Native American from Dunn, North Carolina, played the instrument when he and his band, the Wraymen, recorded scorching, brain-rattling instrumentals, including “Raw-hide” and “Co-manche,” in 1959. It was last seen in photographs of an early-1960s Wraymen gig, being played by one of Wray’s bandmates.

In 2005, soon after Wray passed away, Dickerson got a tip that a man named Fred White, who lived near Washington, D.C., had the guitarlin. Dickerson intended to contact White and make an offer, but White posted it on eBay first. Dickerson won the auction and set out to authenticate the rare find.

He dug through newspaper archives, searching for period-specific listings and photos of live shows. He tracked down and interviewed Wray’s friends and relatives and former bandmates. He got a signed and notarized affidavit from White, stating that he had traded a stack of jazz records to obtain the guitarlin from Wray’s bandmate. His work was thorough enough to meet even the Smithsonian Institution’s burden of proof. After contacting Dickerson in 2010, the museum included the instrument in several exhibits.

“There’s no magic to proving that a guitar is authentic,” Dickerson says. “All it takes is some good old-fashioned detective work.”

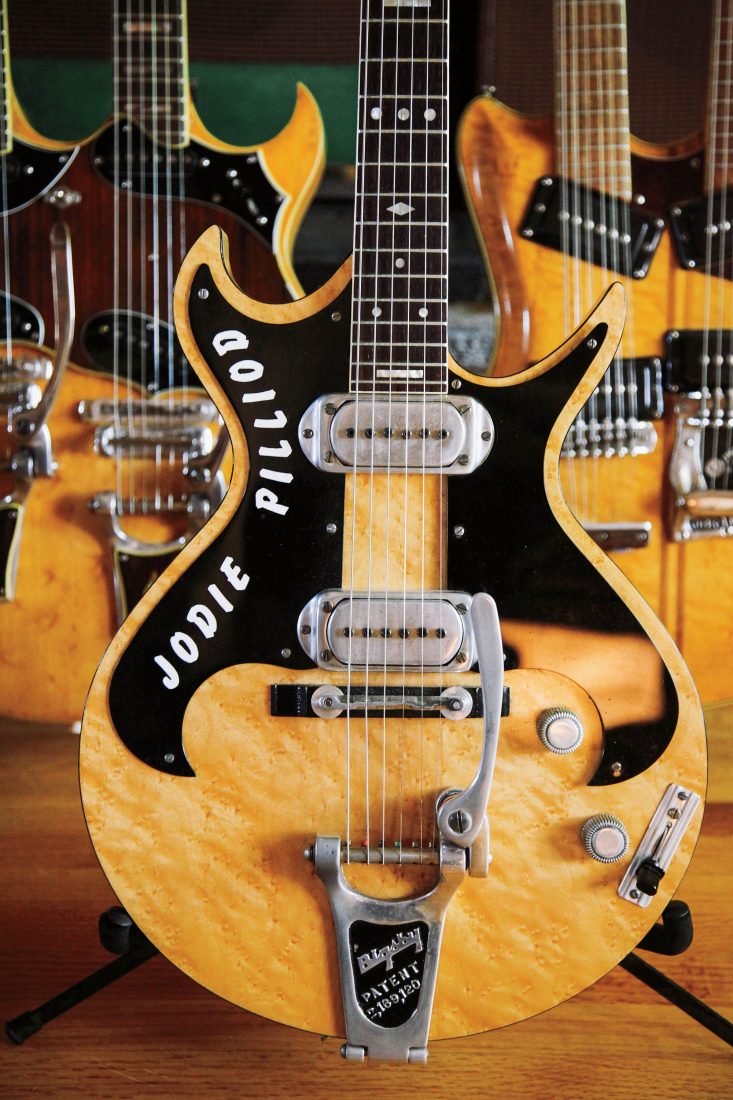

That’s how Dickerson tracked down the prize of his collection, a 1956 Bigsby electric guitar made for Jodie Pilliod, a country-swing musician from Lubbock, Texas. Fewer than twenty-five Bigsby guitars were made, between 1948 and 1956. They were the first solid-body electric guitars, predating even the Fender Telecaster and the Gibson Les Paul. Many of the top country-and-western guitarists played Bigsbys during that era—Merle Travis, for one, and Ernest Tubb’s lead guitarists, Tommy “Butterball” Paige and Billy Byrd. Dickerson had to find this guitar.

He did it by cracking open phone books. Pilliod isn’t exactly Smith or Jones, and Dick-erson found about fifty listings for Pilliods in Texas. In short order he was on the line with Jodie Pilliod’s nephew, who had the guitar—in mint condition, no less. So Dickerson did what any obsessed guitar geek would do: He borrowed the money and bought it. Later, in 2012, when another Bigsby surfaced, it fetched a shocking $266,000 at auction.

But Dickerson gets prickly when pressed about dollars and cents. “People ask me what my collection is worth,” he says. “I find that part of the discussion sort of vulgar. Knowing great musicians bared their own souls through the instruments, that’s the real payoff. That’s what I live for.”

That, and his next great find.