“This is so pretty I’d wear like a brooch.” That’s what my wife, Blair, said when her entrée of bay scallops arrived on an alabaster wave of pureed cauliflower. “Cynthia Wong is a badass.” That’s what I said, later that same night, when I bit into a button of maple flan, shawled in a Tokay-spiked caramel.

A dozen years have passed since Hugh Acheson opened Five & Ten, a white-tablecloth restaurant in Athens, Georgia, with a bare-knuckle approach to flavors. He built his reputation paying homage to the South without bowing to provincial ways. That thinking led to dishes like cornmeal-dusted sweetbreads with tarragon jus and grits custard. And bourbon lobster bisque. And a palate cleanser of cubed watermelon sprinkled with cayenne, inspired by Mexican street food vendors.

At Empire State South, Acheson’s newest restaurant, set, incongruously, on the ground floor of a bank building in Midtown Atlanta, Ryan Smith is the insurgent with his grip on the skillet. You already know Wong, the pastry chef. And you should get to know the sommelier, Steven Grubbs. A madman with a yen for Rieslings and Barolos, he has a talent for touting bottles that manage to be both cheaper and better than you expected.

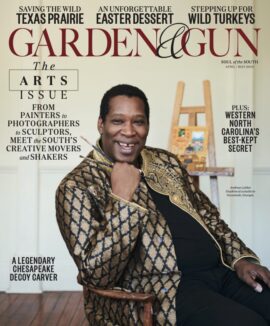

Photo: Rinne Allen

Pastry chef Cynthia Wong.

Acheson originally billed the restaurant as a newfangled meat-and-three, the sort of place where diners could relish a smothered pork chop or a fiddler catfish fillet, paired with sides like braised collards, stone-ground grits, and fried okra. Sure, he sourced better ingredients than the average joint. But the formula was much the same.

Under the leadership of Smith and Wong, Empire State South has gone well beyond the meat-and-three conceit. Other restaurants, inspired by recipes and techniques lifted from antebellum receipt books and plantation ledgers, are making their reps by interpreting various Southern pasts. Instead, Empire State stages expositions of contemporary regional foodways.

The dining room, which faces on a skyscraper-boxed greensward dominated by a bocce ball court, is Farmhouse Moderne. With a little Steampunk thrown in for good measure. Sputnik pendants, outfitted with Edison bulbs, dangle from the ceiling. Scalloped sconces, which recall Aphrodite’s lair, spangle chalkboard-green walls, burnished to an ebony sheen. Service accoutrements reflect the same Jules Verne Spends a Week on the Farm aesthetic. Flats of oysters arrive with cork-stoppered vials of celery mignonette. Instead of employing crystal, Empire State South decants its wine into tempered glass beakers, seemingly borrowed from high school chemistry labs. Servers, dressed in gingham tops and white aprons, deliver drinks with names like Crimson King in gilded-rim coupes.

Photo: Rinne Allen

The house koozie.

The food is daring and unimpeachably delicious: Quenelle of trout with a plum mustardo, served in a pressed glass tray that looks as if it were stolen from my aunt’s house. House-cured ham, with bolls of fromage blanc and pickled green strawberry chowchow. Cold-smoked duck on a divan of persimmon puree, speckled with faro grits. Figgy toffee pudding, goosed with bourbon and butterscotch and crowned with whipped crème fraîche.

Each dish that emerges from the Empire State South kitchen tips its hat to the South. And then lights out for brave new provinces. Based on two recent meals, Blair and I will follow Ryan Smith and Cynthia Wong anywhere they care to lead us.