“I very rarely see cash exchanged, even for just three bucks,” a thirty-one-year-old marketing executive tells the New York Times. When his credit card number was stolen and he had to traffic in actual cash for a few days, he says, it “was sort of a weird, dirty feeling.”

Really? That’s like saying, “Somebody stole my virtual nutrition code, and I had to get nourishment from pieces of a chicken.” Or, no, in deference to vegans, and chickens, let’s put it this way: “I had to get nourishment from these hard orange things that apparently grow in, like, the dirt. Ewww.”

I know, I know, filthy lucre and all that, but why do we make that little thumb-rubbing-the-first-two-fingers gesture when we speak of money? It’s because we still feel money in terms of greenbacks, simoleons—“up-front whip-out,” as they say in Dan Jenkins novels. And I know, coins today are an encumbrance, but what is even more mindless than it was to play slot machines back in the day? It’s to play slot machines now—now that they don’t even pay off in showers of quarters.

And let me ask you this. Say you are enjoying a crawfish boil out on the sidewalk in front of Cosimo’s tavern in New Orleans. Eight dollars for a Styrofoam clamshell holding around a pound and a half chock-full with antennae sticking out. And the burners under the five big pots are whooshing and steam is rising and the mudbugs are getting redder and redder in there, and you ask the man in charge, who has been stirring the pots with a canoe paddle, what that awful overlong-baked-potato-looking thing is that he has pulled out of one of the pots.

“A knee-high stocking,” he explains. Full of spices and garlic and stuff.

“That’s the way my uncle did it,” says a waiting customer. “My aunt would get so mad.”

“My aunt used to say she would know everything was over for her when she started wearing knee-highs,” says another customer. “And then Prince started wearing them.”

And one crawfish has evaded the pot and is scuttling toward Esplanade. From there it’s only thirty miles to the Bonnet Carre Spillway and home.

And people who already have their crawfish are sitting on the curb getting juice down to their chins and up to their elbows.

Would you consider it seemly to use a credit card there?

Furthermore, if money ever goes entirely abstract, think what it will do to the lyrics of Southern songs.

You won’t be hearing about any such poignant personal relationships with money as in Billy Joe Shaver singing sad farewell to his “Bottom Dollar.” You won’t be hearing new artists singing, as Ray Charles did, about a “greenback dollar bill, just a little piece of paper, coated with chlorophyll.” You won’t hear about anybody physically throwing a bottom dollar away, out of pride, as in Johnny Cash’s “Wrinkled, Crinkled, Wadded Dollar Bill.”

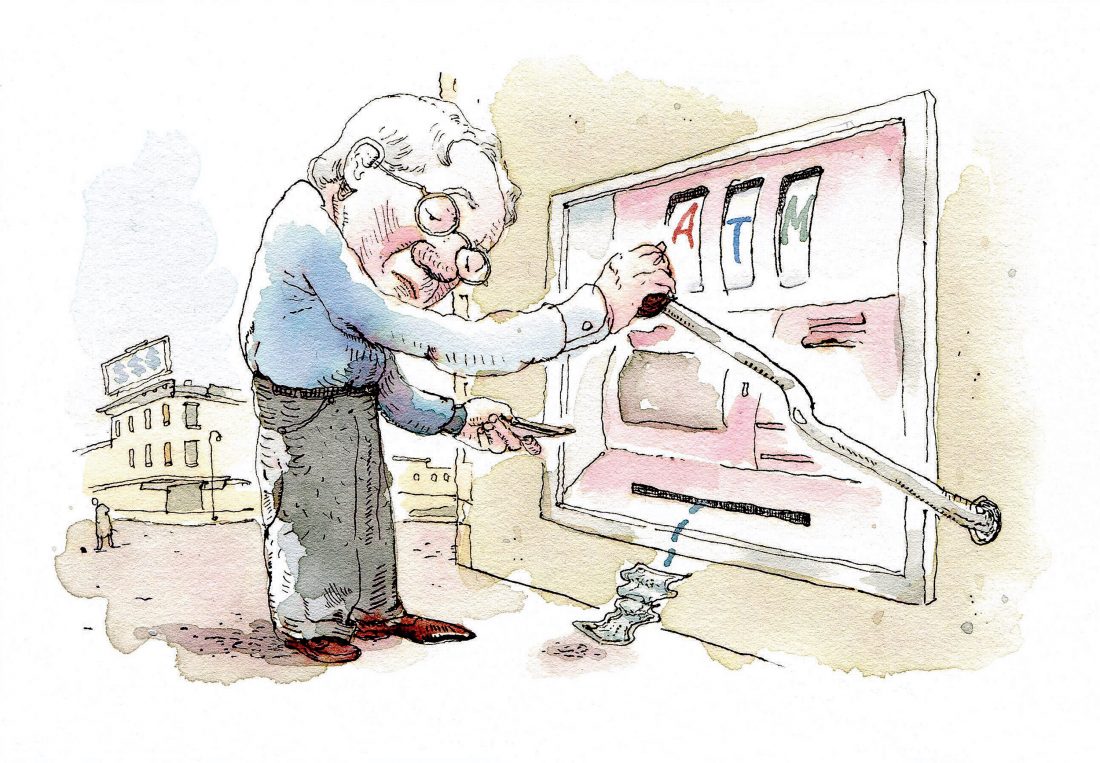

By the way, if you want to see Cash actually messing with literal cash, check out the 1984 video for “Chicken in Black” on YouTube. As the story goes, Cash recorded the song—the worst song he could conceive of—to force Columbia to let him out of his contract. The song tells how the Man in Black had headaches and a surgeon crossed him up by putting Johnny’s brain in a chicken and giving Johnny the brain of a bank robber. So the chicken, along with the surgeon, is making a lot of money singing Johnny’s songs, and Johnny can’t resist the impulse to rob banks. I highly recommend this video. It is so much more real than one of those high-finance computer heist movies.

One more point. In “Dang Me,” the great Roger Miller sings about “spending the groceries and half the rent,” ordering rounds of drinks—and although you sometimes see the next line quoted as “Like fourteen dollars and twenty-seven cents,” that is wrong. Nobody’s groceries, let alone rent, are in that price range. What old Roger sings is “I lack fourteen dollars having twenty-seven cents.” (He pronounces lack as a lot like like, as country folks will do.) That’s a real hard-money definition of being in the red.