She had been missing for three days. We had put a reward notice with a photograph and dollar signs in the window of the nearest store, seven miles away across open fields and swampy woods. The local farmers, tractor drivers, and crop-duster pilots had all been alerted to look out for a burly German shepherd/Lab/hound mix with outsize ears, belonging to the Englishman and his wife in Dr. Foose’s old house.

Most of them already knew Savanna. They had seen her charging after their pickup trucks, or trotting along the one paved road in this remote corner of the Mississippi Delta. On several occasions, they had seen me, or my wife, Mariah, driving up and down the levees and calling out her name in vain. Savanna was fairly obedient at close quarters by then, but she’s always had a deep aversion to coming when called, even when I tried walking her with roast chicken tied to my belt. She has her sweet, soppy, affectionate side and takes her guarding responsibilities seriously, but she’s a rebel and a runaway at heart, a scrapper and a bruiser. We probably should have named her Big Sue.

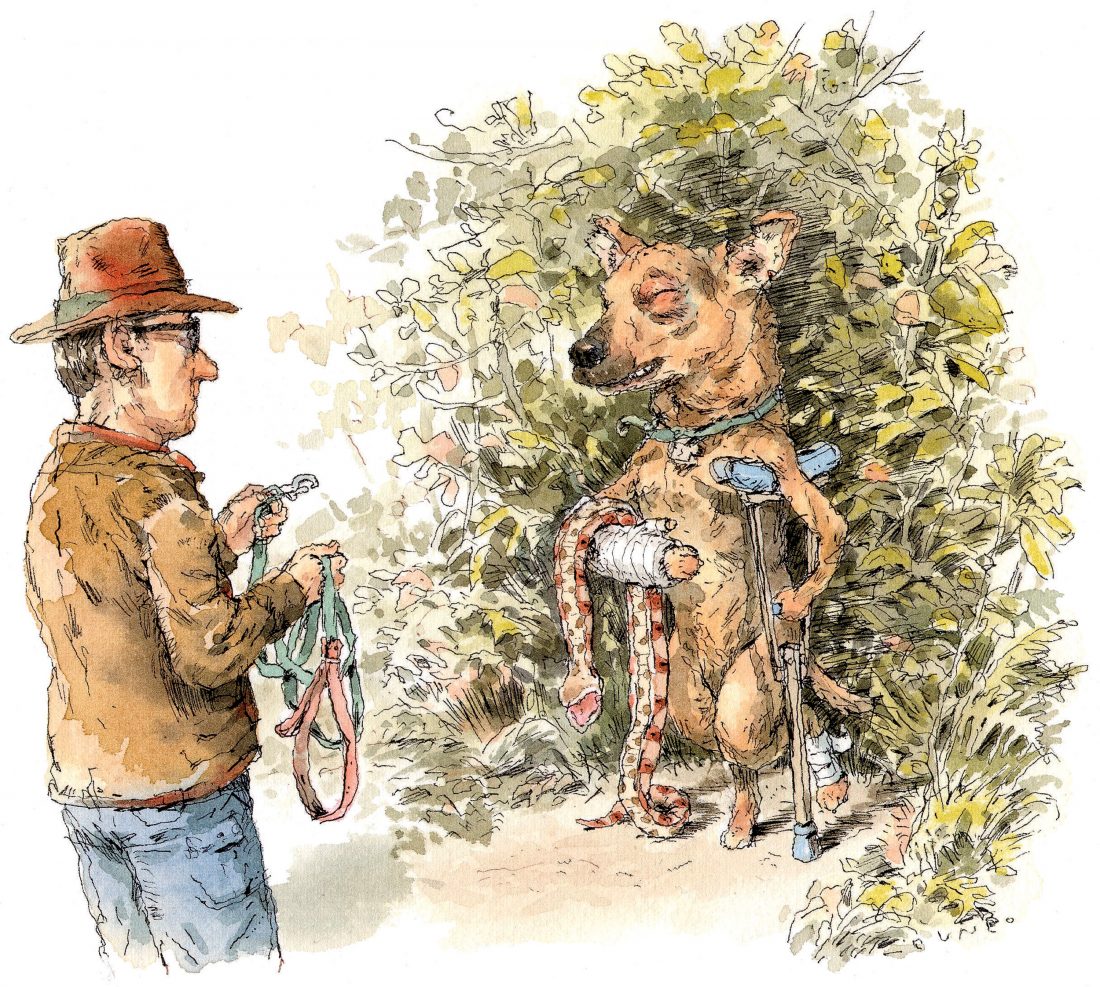

We had given her up for dead a few times before, only to spot her in the distance limping home after another wild adventure in the woods. She would come into the kitchen panting like a freight train, covered in mud, often reeking of the rotten carcasses she had rolled in. That was her idea of a good night out. It wasn’t fun unless it incurred a vet bill. Sooner or later, we told ourselves, she was going to disappear for good, and we would never know what killed her. This felt like that time. We kept driving around and looking for her, but I was now checking the sky for circling vultures.

There were so many ways for a dog to die out here: alligators, wild hogs, coyotes, water moccasins, even a buck, or a boar raccoon. The way she chased vehicles was painful to watch, because she would snap at the wheels, but it seemed too cruel to keep her penned up. We had agonized back and forth on this question. No one else who lived out here kept their dogs penned, or walked them on the leash. It was a culture of loose country dogs who came in at night, and we had reluctantly let Savanna join it. We worried constantly about her safety, but we’d never seen her so happy and fulfilled. She loved the freedom to run, chase, and hunt more than anything else.

As far as we could tell, she had grown up as a loose farm pup around Nacogdoches, Texas. A friend found her there at the lake, without collar, tags, or owner, and drove her to Tucson, Arizona, where we lived at the time. She seemed so calm and docile at first, mainly interested in sleeping, and we attributed it to the long journey. Two weeks later, we discovered that she was pregnant, with a blocked artery and fifteen puppies dying inside her. A saintly veterinarian performed an emergency operation and blood transfusion, slept by Savanna’s side all night, operated again in the morning, and then charged us a token fee.

The fifteen pups were by three different daddies, said the vet, including a mastiff, and it had all happened on her first heat. Our friends joked that she was East Texas trash, barepaw and pregnant, as we nursed her through a long convalescence. Once she regained her strength, she turned into an entirely different dog. She lunged and snapped at us in the backyard. She broke out and escaped at every opportunity. Like Cool Hand Luke, she had rabbit in her, and was born to run. Once I found her chasing cars in four lanes of traffic going fifty-five miles an hour.

We applied a combination of strict discipline, daily exercise and training sessions, and affection. She responded with willfulness, disobedience, and hooliganism. We were her jailers. All she wanted to do was get away from us and regain the freedom she had enjoyed at Nacogdoches Lake.

Once we took her camping in the parched rocky desert of southwestern Arizona. Her pads got torn up while hiking on the leash. By the time we got back to camp, she could barely walk, and lay down looking piteous. She was also hungry and thirsty, and before feeding her or filling her water bowl, I did the thing that we had learned never to do. I took off her leash.

She struggled to her feet, gave us a backward look that seemed to say, “Sorry, it’s just who I am,” and hobbled off into a vast waterless wilderness where she would surely have died if I hadn’t chased her down and reattached the leash. We never took her camping again. And we never let her off the leash again in an unsecured area, until a long and winding road brought us to the Delta.

From Tucson we moved to New York City. The plan was to stay for a year, and then move somewhere else. Savanna hated the city—the noise, peeing and pooping on the leash, living in a tiny light-starved apartment with no backyard. She lay there for hours with her head on her paws, eyes open and mournful, a caricature of canine despondency. After a few months, my friend Martha Foose the cookbook writer persuaded me to buy her father’s house near Pluto, Mississippi, in the wilds of the Delta, and we all moved again.

At first, we kept Savanna on the leash. We couldn’t imagine her showing caution around a snake or an alligator, and we worried that she would simply run off and never return. But the idea of keeping a dog confined amid thousands of acres of unfenced land, for the rest of her life, also seemed impractical, and even morally objectionable. Why should she be the only dog around here under house arrest? So we gave her freedom, and at first, she stayed close to the house and barked to be let inside at sundown. We had never seen her so happy, obedient, or well behaved.

Then she started going farther afield, following her nose after the countless wild animals that lived on and around the property. She fought raccoons, learned the hard way about skunks, and killed armadillos by drowning them in irrigation ditches. Sometimes she got lucky with a rabbit or a squirrel, and perhaps this fed her dreams of self-sufficient freedom. She’d become increasingly feral, I suppose, although she’d never been gone this long before.

After seventy hours, hope slipped away, and we crossed over into mourning. She had died doing what she loved, we told ourselves, and maybe the next dog would be purebred. Then the telephone rang. A woman with a deep Delta drawl said, “Hi, this is Bessie Outlaw over by Silver City. I think I’ve got your dog. She came to our wedding, and we all thought she belonged to one of the guests

The Outlaw house sat on an old Indian mound on the other side of the Yazoo River, which flowed with a powerful current and was full of alligators and water moccasins. Savanna must have swum across it and then continued onward until her nostrils picked up the aromas of the Outlaw family wedding feast. “She was very well behaved,” Miss Bessie said. “People were feeding her meatballs and chicken wings. After three days everybody left and the dog was still here. That’s when I checked her collar and found your number.”

Savanna looked chagrined, and relieved to see us. She behaved perfectly for weeks afterward, staying around the house and coming in at sunset. Then her deeper impulses took over again, and she disappeared for two days. This time she came home with a sucking puncture wound in her chest, where a wild hog had gored her. We love her too much to let that happen again, so now she is under confinement, back on the leash, and just starting to mellow with age. And in the hardware store, and at the bank and the supermarket, people are always asking me, “That dog of yours crashed any more weddings lately?”