He wasn’t a good dog. That was the strangest part. Even when he was a puppy, Muffin, our cairn terrier, was yappy and mean, calculating and chewy.

His unpleasant personality may, in fairness, not have been his fault. Our block was a particularly staid stretch of South of Broad Charleston—the sort of place where a bench painted the wrong shade of green could cause a neighborhood uproar. An old-money street, frigid toward children, where shining hunting spaniels shadowed their masters with purpose. These dogs bore elegant, worthy names like Plantagenet, Woodrow, and Artemis. How could a dog, a terrier, called Muffin exist in such a place without holding a grudge?

My parents had moved us from the North (we quickly learned to capitalize the region, as if it were a different country) for university and medical jobs. Mom and Dad were geeks; they didn’t care about fitting in. They bought our rambling Victorian on the cheap from an old Charleston family who were unloading the place after a Faulkneresque bout of ruin and suicide. “Just ignore the bloodstains on the carpet,” my father liked to say to guests, secretly testing how long it took them to leave after that statement sank in.

Even among the new rules of etiquette, my parents still clung to their New York senses of humor. And when it came to populating their Southern manor, they wanted a funny dog. It wasn’t that they didn’t like well-behaved, reasonable canines. But why, they said, pretend to be something you’re not? After all, we were terrier people. We shrieked, we barked, we scratched places better left untouched.

It was my father’s job, one Christmas Eve in the 1970s, to procure the specimen from a litter “out in the country.” Highway 17 south to the peanut stand, the directions read. Turn at the dirt road, and honk when you see the blue trailer. If you get lost, DO NOT get out of your car. Bring dimes. Go back to the gas station in Walterboro and call.

The bundle seemed correct—fluffy, waggy, all that. My father felt good about handing over the two hundred dollars. There were papers, and the breeders looked, if not friendly, exactly, dog literate. Then, just as the pair hit the Ashley River bridge, the new dog leaped through the air and attached his adorable puppy teeth—all twenty-eight of them—an inch deep into my father’s exposed wrist.

You see, no matter how much we tried to ignore it, the thing was that Muffin sort of sucked. “This one’s a nipper!” my mother cried on Christmas morning as my brother’s toes bled through his Star Wars slippers. “It’s nothing. All puppies do that. Just don’t put him near your eyes, nose, ears, or any other parts you happen to like.”

Oh, Muffin. Bred to stalk rodents in the cool hills of Scotland, the dog lost his inner quest to move in the Southern climate. By three, his belly swelled over his legs, giving him the look of a hairy manatee. Despite thousands spent on special flea medicine, he developed a skin condition that caused incessant itching, quelled only by humping the furniture. A stench resembling that of a bloated whale persisted despite weekly shampoos. Watchdog ability? After sleeping through the day and evening, he would spring alive at 3:00 a.m., announcing, with a piercing yap, every gnat that happened by the back door screen.

It wasn’t that we didn’t love the animal. In those early years, my brother and I were outsiders. After long days of being shunned at school, we would limp home and throw our arms around our greasy canine life raft. But Muffin was indifferent to our affection. In fact, as if to prove this, every month or so he would rouse himself enough to shoot out the front door. My father, who by now was eyeing the Woodrows of the block with envy, would quietly shrug his shoulders and let him leave. Yet Muffin always returned, most likely due to the collar my mother had gotten made: If found, please muzzle and bring back to 50 Church Street.

On the day after my sixteenth birthday—September 21, 1989— Hurricane Hugo pressed down on what was, by then, our city. My mother, ever the scientist, insisted that the data showed it would not hit Charleston directly. Those people leaving were fools! She filled the bathtub with water and had my father close the shutters. We didn’t know that staying was a terrible idea until the gathered news trucks took off. “We’re out of here,” the reporters shouted to my brother and me over the rising wind. “Hope we see you on the other side!”

As the rain started in, my mother allowed us to drink beer. She sent us upstairs with one can of Coors each, thinking the alcohol would put us to sleep. What she didn’t realize was that there is no way to sleep through a hurricane because there is a locomotive of wind hitting on four sides. For an hour or so my brother and I sat in our beds on the top floor, watching our bedroom walls dance in and out like Jell-O. These were lovely rooms, usually full of light due to the large, plentiful windows. Now the rain was coming down so fast it looked as if a fire hose was pointed toward the glass.

And then, Muffin woke out of his coma and—for the first and only time in his life—did something right. He ran upstairs to our rooms. He barked. He circled. He told us, in no uncertain terms, to get the hell away from the windows and to come with him, to the dark, airless hallway in the bottom center of the house.

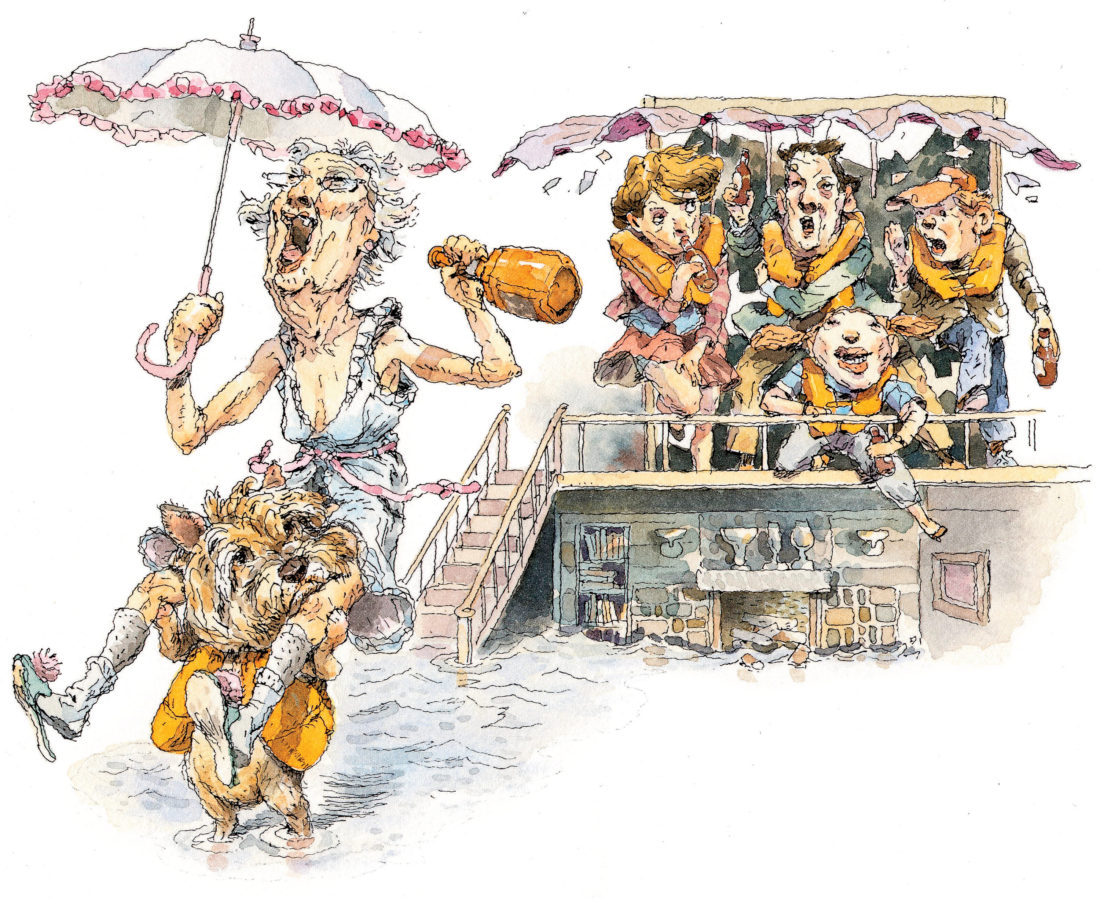

“Follow Muffin!” my father cried. It seemed a slim hope, to trail a stinky terrier with no credentials, but we did it, bringing our pillows and blankets to the spot on the first floor where he commanded us to settle. Minutes later, windows began to pop like balloons in the bedrooms we’d previously occupied. In the back of the house, where my brother had been listening to the weather radio, the roof blew off with a sickening crack. The water rose through the basement, licking the front door, yet stopped short of the landing the dog had chosen for us.

Did Muffin actually save us? Probably not. But he did get us moving and kept us away from the glass. If we ventured away from him, he growled. When my father peeked out the door during the eye of the storm, he barked. It was as if, for ten hours, he was taken over by the soul of Old Yeller. He actually gave a crap.

We sat huddled as a clan, foolish outliers, our hopes pinned to an animal no one believed in. Then the wind died, the sun came out, and the town stank of pluff mud. We were together, alive.

At this point, Muffin waddled back into his career of sucking. He pissed on carpets and ran away until, at nineteen, he gave one last bitter sigh and died. Now, years later, we have all spun off into other orbits. The old house is sold, though my mother lives around the corner in a more modern version. She has cairn terriers again, two of them. They gnaw on doors and have to be kept away from her grandchildren because they bite babies. “Careful,” she said when we met, “this one nips.”