He was just three months old when we brought him home from an animal shelter in rural Vermont. He was small and scared, and clung to me in the car for the forty-minute ride to his new home. When we pulled into the driveway, he promptly threw up down the front of my suede jacket. I didn’t care; David, my then husband, and I knew this was simply evidence of a delicate transition. Of course, we didn’t realize at the time that he would throw up on a regular basis following no emotional trauma at all, merely after eating grass or organic fish fertilizer or chicken bones foraged from the garbage can. But this, we came to learn, is common for hound dogs.

“The brown hound from the town pound,” David softly sang into his long velvet ears when they snuggled on the couch. We named him Leon. We originally called him Coeur de Lion, but it was a mouthful to shout out the back door, so our affectation happily transmuted into Leon.

Leon took about ten seconds to reveal his personality: Once inside his new house, he started barking and charging at his own small reflection in the smoky glass of the dishwasher and stove. We laughed till we cried, then taped up newspaper to keep him from repeatedly bonking his head on the appliances.

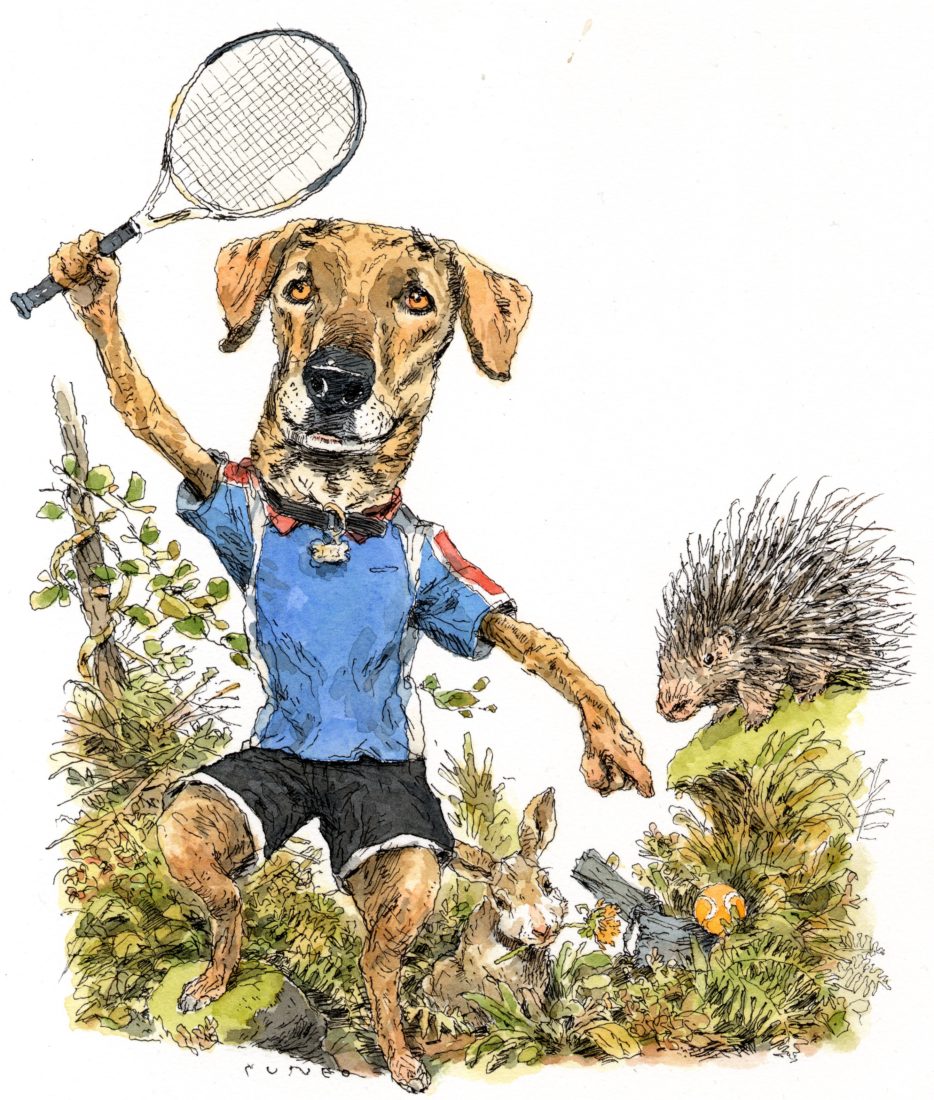

Leon was brown, as you know from David’s song, but not just any brown: a lovely tawny chestnut, covered in beautiful brindled stripes of café au lait, black, and orange. His eyes were a deep liquid chocolate outlined in black as deftly applied as the kohl of an Indian beauty. His noble Roman nose (read: big) ended in soft black leather that we would teasingly say would make a fine purse or pair of tiny slippers.

He was a funny, smart, curious dog who liked to work, to accomplish tasks, the harder the better. He was also one of the most expressive dogs I’ve ever known, with the sensitivity and melodrama of a silent movie actor. He deplored being bored, which generally happened anytime we weren’t playing with him. We taught him games, on which he taught us variations.

He especially loved to fetch a tennis ball thrown down the long steep hill that connected our two meadows on a hilltop. The farther and more obscurely you could throw the ball, the better. He was thrilled when he would lose sight of it and had to track the ball by scent. He’d work for twenty minutes covering the area in a systematic and complex series of zigzags. In the summer and fall when tall grasses and wildflowers crowded the meadows, all we could see of him was his wagging tail as he rooted around. Long after we’d given up and retired to the porch chairs with drink in hand (coffee or martini, depending on the time of day), Leon would suddenly reappear, victorious, with the slobber-covered ball. We’d try to wear him out but often pooped ourselves out first.

David and I used to say to each other, “Are you going outside to throw the ball to him or shall I?” At the mere whisper of the word outside or ball, Leon would be up like a shot and at the back door staring fixedly at the shelf holding his tennis balls. Occasionally David teased him by saying “cross-eyed, cross-eyed,” which sounded suspiciously like you-know-what. Leon’s eyes would widen, he’d cock his head with ears at perfect right angles, and he’d stare at you to clarify the word. We thought we had the problem licked by spelling o-u-t-s-i-d-e and b-a-l-l, but I’ll be damned, he figured that out, too.

From anywhere in the house, these sounds would bring Leon running: the can opener attaching itself to a dog food can and no other; the opening of a ziplock bag containing Vermont cheddar cheese; ice cubes clinking into a glass. And because these sounds generally happened on a regular schedule, he started to appear slightly ahead of the sounds in order to more quickly receive dinner, chunks of cheese, and vermouth-soaked ice cubes. Leon performed a complex routine with David as payment for these treats: sit, shake, kiss (a bop on the nose), jump to a double high five, lie down, and roll over in both directions. I told David that after all that, Leon deserved the entire martini.

There was an element of fate when we found Leon. He was a Plott hound, the state dog of North Carolina, our home state. We were all Southern expats hiding out in Vermont, enjoying the breathtaking, exotic landscape of rolling green hills dotted with white sheep and weathered red barns, and the cool of the summers. But as for many expats, the call of home was strong: family dinners, magnolias, familiar accents, the rhythm of life. And it did seem right that Leon should live below the Mason-Dixon Line. So we packed up and made the move back to the sweet, literary-minded small town of Hillsborough, North Carolina.

By that time, we had added two babies of a less hairy nature to our family. Initially I had worried that Leon, who was used to receiving the attention of the firstborn, would have a hard time being relegated to the beloved family dog. But he took it in stride, merely adding the kids to his pack. What he couldn’t take in stride, however, was our new postage-stamp backyard in the middle of our historic downtown neighborhood. Leon had been raised roaming fifty acres on a hilltop. Not a neighbor in sight, just the deer, porcupines, and vast woods that were his territory. We foolishly hadn’t socialized him, and his alpha tendencies took over with a vengeance.

Leon would throw himself against the white picket fence, in a terrifying fury, any time a neighbor would walk by. He would do the same inside the house when he heard or caught sight of a passerby. We took him for endless walks, worked with a trainer, offered rewards, punishment, love, clear commands—did all we could do. I knew it was a matter of time before he learned to leap the fence or simply dashed out an open door. Most important, it was clear he was miserable. And so we did the best, most painful thing we knew to do: found him a new home that better suited his needs.

And what a home it was: a farm in Virginia (not a euphemism) with alpacas, pigs, other dogs, and a lot of wide-open space. The owner was a professor and true animal lover whom we found after many hours following up on leads from one hound rescue society to another. I remember the day David, sobbing, packed Leon into the car with his treats and the L.L.Bean sleeping bag he used as a bed, and drove him across the state line while I, at home with the kids, sat on the kitchen floor and wept.

It was shocking to be without Leon. The kids were toddlers and, thankfully, quickly accepted it as the new normal. But David and I mourned a long time; it was years before we considered adopting another dog. I never doubted it was the right decision, though—a peace settled over the house as the daily stress and fear of Leon’s misery disappeared. The saving grace was that Leon was happy, and swiftly adapted to farm life, spending his days roaming with his new buddies, able to breathe again. The professor kindly emailed us pictures and reports in the ensuing months. Over time, our desolation gave way to good memories and celebration of the time we’d spent together.

Even though there have been other pets in our lives, Leon was the first and holds a special place in our family lore. The kids still love to look at pictures of him—a portrait of Leon wearing a daisy chain sits on our front hall table—and to hear the stories of his antics. As they would for a favorite dark fairy tale, they periodically ask to hear the story of his leaving, again absorbing the pain of that tearful choice made by their parents before envisioning him romping around with the alpacas. Even absent, Leon taught our young family that love and grief coexist, and both must be honored.

This article appears in the June/July 2020 issue of Garden & Gun. Start your subscription here or give a gift subscription here.