I had a good dog. He was such a good dog that when he died in my arms about five years ago, I decided, at my age, I just wouldn’t get another one. After all, I’d had Cormac for sixteen years. But sometimes a dog comes along who doesn’t give a damn how old you are.

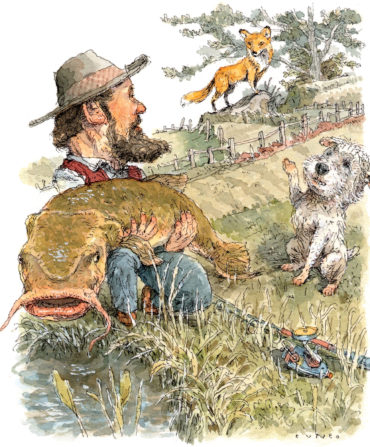

Doctors do care. They might say something like, “Well, this is usually a benign condition”—in my case, an ocular migraine—“but at your age, we better run some tests.” A dog, on the other hand, might take one look at you out in the Alabama woods, him running with his squirrel-hunting pack of feists while you amble along with his owner, and say, I think you may be the friend I didn’t know I’d lost. Doesn’t trouble himself about your white hair and whiskers or the almost seven decades you’ve accumulated. Cuts himself out of the pack and keeps circling back to check on you. Comes running back down the ridge, kicking up dry leaves in his wake, and jumps up on you and drills his youthful amber eyes deep into your shaky old hypertensive heart. You want to come run with me?

That’s just what Bobby did. About five times.

“This guy not like to hunt?” I asked my friend Benny on that outing last December.

“He loves it. But it’s also in his genes to look after the master.”

“I’m not his master. You are.”

“Bobby might feel differently about that,” Benny said, grinning. “You want him?”

“Oh, hell no! He’s a pup. Too much energy. What is he, like a year old?”

“Ten months.”

“No, no, no,” I yelped. “Anyway, I’m still not over losing Cormac.”

When Cormac died, it was real tough. I’d lost him once before, which was a different kind of nightmare. I wrote a book about the experience, Cormac: The Tale of a Dog Gone Missing. The CliffsNotes version: I left him with a friend while I was touring with a novel, and Cormac bolted during a thunderstorm. I looked for him for thirty days. Door to door, picture in hand, “Have you seen my dog?” Then, one tip led to another tip, and I finally found him. He was up for adoption on the Internet—twelve hundred miles from home, after being picked up from the pound and taken north by a rescue group. I got Cormac back, and for the next nine years, I was careful to a fault keeping an eye on my big rock of a golden retriever, a bear who had me caught in the rhythm of his blood muscle. And one dog like that was enough for me.

As we followed the pack through the woods, bothering out squirrels from the treetops, Benny could see I was warming on Bobby more each time he checked on me. Asked me again did I want to take him. I said no.

“Anyway, I wouldn’t want a little dog,” I said. This black-and-white Bobby was all of twenty pounds. “I would want a waist- high armful of dog. And, like, are his ears too big?”

During the course of that single chilly afternoon, the hot-wired terrier mix with his stand-up tail would gaze at me, eyes like a spell that bit by bit rolled the stone away. I wasn’t prepared for the way his look “smoothed me,” as my grandma used to say. And by the end of the day, I was ready to change his last name to Brewer.

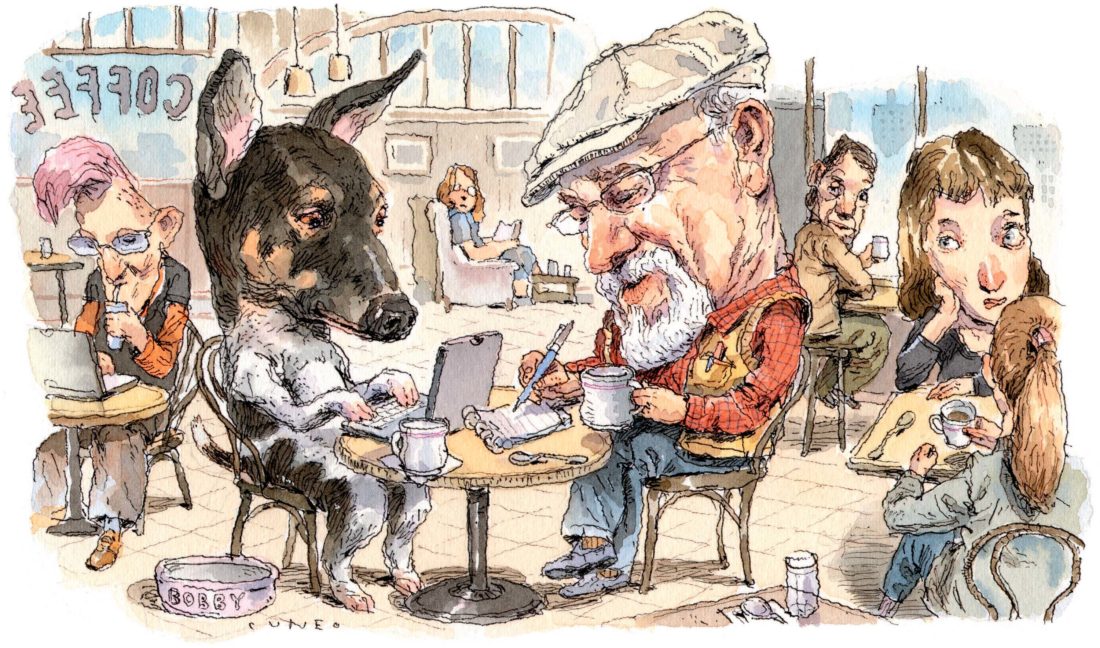

Since moving with me to Fairhope, Bobby’s not a squirrel dog anymore—he’s a city dog. In the hunting pack, he slept in a shed on a wide plank beside a chicken coop. Bob- by the hunting dog had never known a collar or a leash, a soapy bath, the inside of an automobile or a house. Now he hangs out with me at coffee shops and sleeps in like a lazy poet with a latte habit. Like matching body parts, we are a pair.

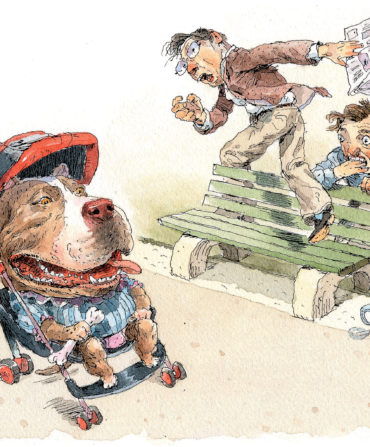

But something happened during a recent run to a doctor upstate to check on my “visual anomaly” that reminded me of the difference in our ages. See, Bobby loves cows. At sixty miles an hour he can spy a lone cow in a pasture miles distant on a hill- side underneath an oak. And on our drive to Tuscaloosa, stretches of long straight two-lane roads through rolling farmlands showed him hundreds of them. He’d make little yelps in the cab of my truck.

“Hey, Bobby, here’s a little treat for you. Up ahead I see about twenty cows right up to the fence. I’ll stop and let you say hello out the window.” No cars in sight in either direction for more than a mile. I was going ten, fifteen miles an hour, slowing, coming to a stop in fifty yards. Then I screwed up. I started the window down on his side to that sweet spot I deem a safe opening. But before I hit my mark, Bobby had his head out, paws hung on the top edge of the glass, pulling and squirming. Then he launched.

Sonofabitch! In the rearview mirror I saw him roll to a stop on the shoulder of the road and assume his attack stance. I parked in the highway, door open, truck still running, and, over the thunder-thumping of my heart, I screamed his name. From the stress of the jump, I guess, he began trot- ting in the opposite direction. Thank God, Benny had taught all his dogs to come at the first syllable of their names. “It’ll save their lives on any given day,” he had preached.

“Bobby!” I said again, and he turned as if yanked by a leash and flew to my open door and mounted up. He bled from an abrasion on his right shoulder. I almost cried, because that’s what the elderly do.

When I got him snuggled beside me on the seat, I called Benny for him to con- sole me. He did. Said he had a dog jump out the rear window of an old Chevy van. “Her name was Sugar, and that girl was my heart. By the time I got stopped, she was running full tilt into the woods. I don’t know why. I never saw her again.”

Bobby’s near escape made me doubt myself—can I really handle a young dog’s energy? Then I remember that it’s him and me, from breakfast to bedtime, when he sleeps right beside me. If I run an errand, he runs along. When I eat an apple, Bobby gets a bite. He doesn’t go to movies with me yet. But we’re working on some clever disguises.

Bobby is not that armful of a dog that Cormac was. But he is a heartful. And way better medicine than any doctor could think up.