At Hot Springs National Park in central Arkansas, an estimated 700,000 gallons of hot water—143° F hot—pours out of a mountainside each day in the form of thermal springs that have long attracted visitors who believe in the water’s healing powers. “The reason the city of Hot Springs is here is because the springs are here,” says Tom Hill, the park’s museum curator and unofficial historian. This year, the park celebrates its centennial anniversary, but the Hot Springs story starts long before that.

“The water people bathe in as hot springs today fell as rain when the pyramids were being built in Egypt,” Hill says. When rain falls in the “recharge zone” a few miles outside the park, it spends 4,300 years percolating into the hot belly of the earth, eventually reaching depths of 6,000 feet. Then, over one hundred years, pressure forces the water along a fault line moving back up the mountain, and it emerges in the form of dozens of odorless, colorless hot springs.

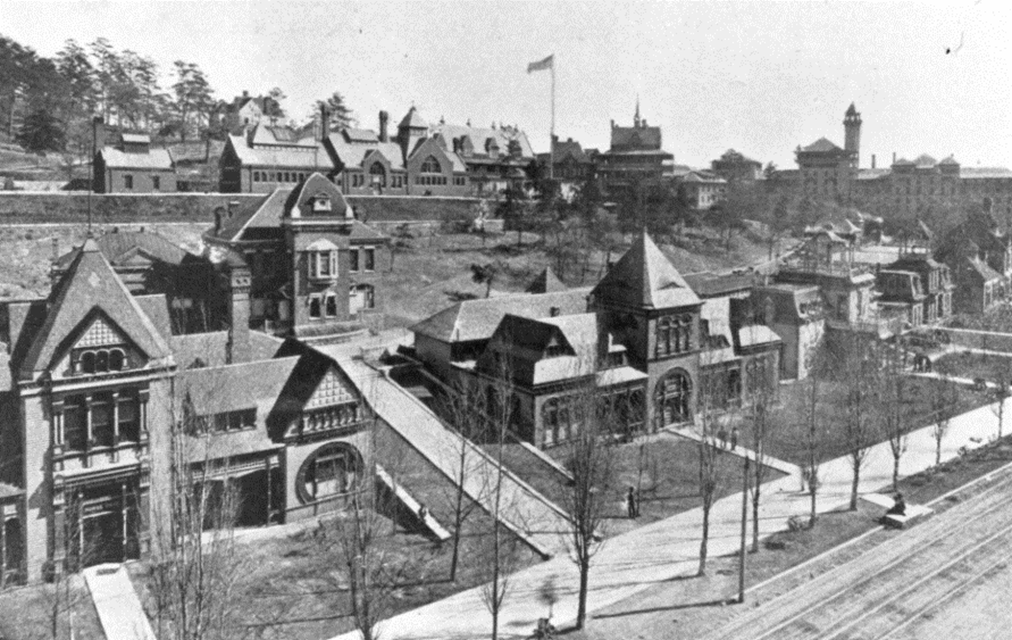

Today, visitors can still wander along Bathhouse Row, eight historic bathhouses that make up the heart of the town that sprang up around the thermal waters in the early 1800s. By the time the area became a National Park in 1921 (it was already protected as a preserve that President Andrew Jackson set aside in 1832), the first bathhouses, all wooden, were already open, along with places for the bathers to stay and eat. “Hot Springs has long had the slogan, ‘America’s First Resort,’” Hill says. “But in reality, when it all started, it was people’s last resort.”

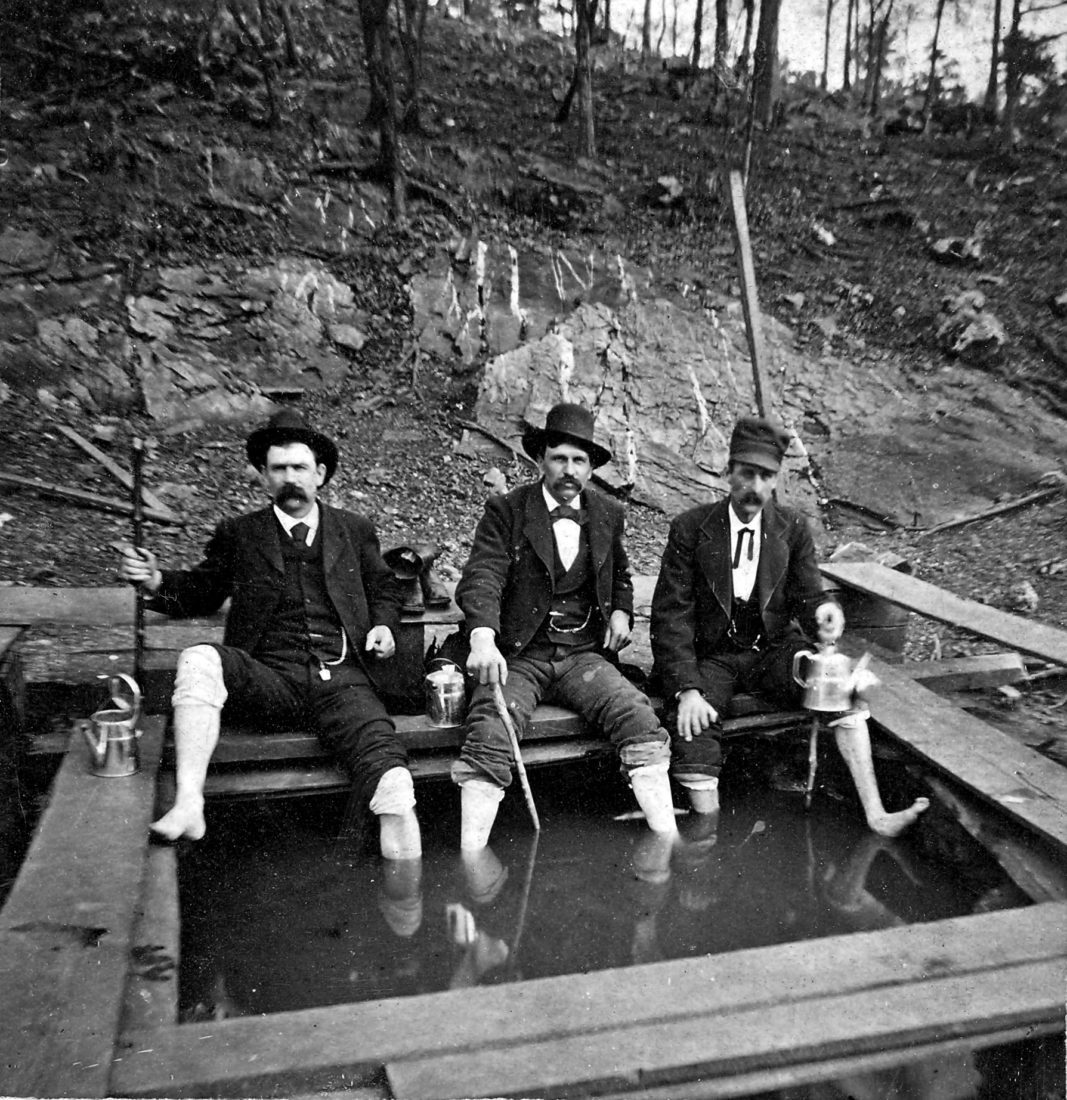

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, he explains, therapeutic bathing was actually at a doctor’s prescription. “The idea behind the bathing itself was that you were to elevate your body temperature to make you sweat out impurities.” For a full regimen, a patient would stay for three weeks, drinking the mineral-rich thermal waters, bathing and doing physical therapy by morning and then exercising and socializing by afternoon.

Hill points out that therapeutic bathing likely didn’t cure people outright, but it certainly helped to some degree. “In the 1800s, they were bathing regularly here, which didn’t always happen at home, drinking clean water, which didn’t always happen at home, and relaxing and trying to get better, which probably couldn’t happen at home.”

With World War II came the rise of modern medicine, and the bathing industry began to decline. The flow of visitors slowed to a trickle, and one by one, the bathhouses closed down. The most opulent and expensive, the Fordyce, shut its doors in 1962, the Maurice closed in 1974, and the Lamar followed in 1985. Only one of the original locations survived in continuous operation—the Buckstaff, which has now been open since 1912.

“Over time, Hot Springs began to evolve,” Hill says. “People would still come to bathe, but they’d stay to play and gamble, and we became a vacation instead of a medical journey.” Hill calculates that in 1921, about 10,000 people per month would have arrived by rail alone for their bathing treatments. Now, visitors come for a single spa experience, on a weekend trip, or for the horse races at Oaklawn.

After a century, Hot Springs is still growing and adapting. The Reserve boutique hotel opened earlier this year. One of the bathhouses on Bathhouse Row is now a brewery that features the thermal waters as its main ingredient; another features an art gallery, and another houses a hotel with thermal spas in each room. The Quapaw now offers a more contemporary bathing experience in the form of communal thermal pools. And the National Park is currently accepting proposals for what to do with two more historic bathhouse buildings.

But history and tradition still hold a place here. Fountains still flow with thermal waters for drinking, and the Buckstaff Bathhouse is still operating according to the original prescription: a personal bath attendant, individual tubs, hot showers and hot towels, and cups of cooled thermal waters to drink. “The National Park Service does more than preserve scenery and wild landscapes,” Hill says. “Hot Springs is one of those places where we want to preserve the human story—the history and culture—as well as the science and the nature of the spot.”