For forty-year-old artist Kirk Henriques, the studio is a space for freedom and self-exploration. In his workspace in Woodstock, Georgia, he bends over pieces of fiberglass mesh and pours, layers, tears, sands, collages, and most importantly, scrapes. “I love scraping,” Henriques says. “I love distressed, chipped paint because it has so much already built into the surface—a concept of time, histories, and memories. There’s a constant back-and-forth of adding and taking away.”

Henriques’s labor-intensive, tactile studio practice gives life to highly textured and layered artwork. The bumpy topographic surfaces are imperfect with ragged edges—a stylistic quality the artist fully embraces as a rejection of tradition and rigid boxes, historical and metaphorical. This complexity is an integral part of Henriques’s work and identity: As a child of Jamaican immigrants, he recalls trying to figure out where he belonged, feeling equally out of place in New York and in Georgia, where he attended the Savannah College of Art and Design. “At a young age, I kind of understood there are different nuances to identity, [a person’s] story, where they come from. You can’t get all those nuances in broad strokes,” he says. “I was too Southern to be a true New Yorker, and I had Caribbean parents. And that made me different as a Southerner.”

Recently, in his new role as the artist-in-residence at West Palm Beach’s New Wave, a program designed to empower emerging artists, Henriques has expanded his exploration of technique and symbols of identity. Armed with a mop heavy with paint, he investigates Southern Slab culture and cars as an extension of self. Expressive, gestural mop strokes convey movement—like a swipe of teal that represents his Jamaican aunt’s 1976 Volkswagen Beetle. During his six-week residency, which runs until January 2, 2023, his studio is open to the public, and two of his works are featured in a group exhibition in Palm Beach’s TW Fine Art Gallery alongside past New Wave artists in residence, also until January 2.

“In art history, you’re told you have to use these materials, or this is what a painter looks like,” the artist says. Experimentation with technique and a range of tools allows Henriques to have a dialogue with his pieces rather than fully control them—a kind of freedom he says he craved after leaving his role in the film and music video production industry in New York. “I’d rather let the work inform how it’s made, what it’s made of. I like that it has buy-in and say.”

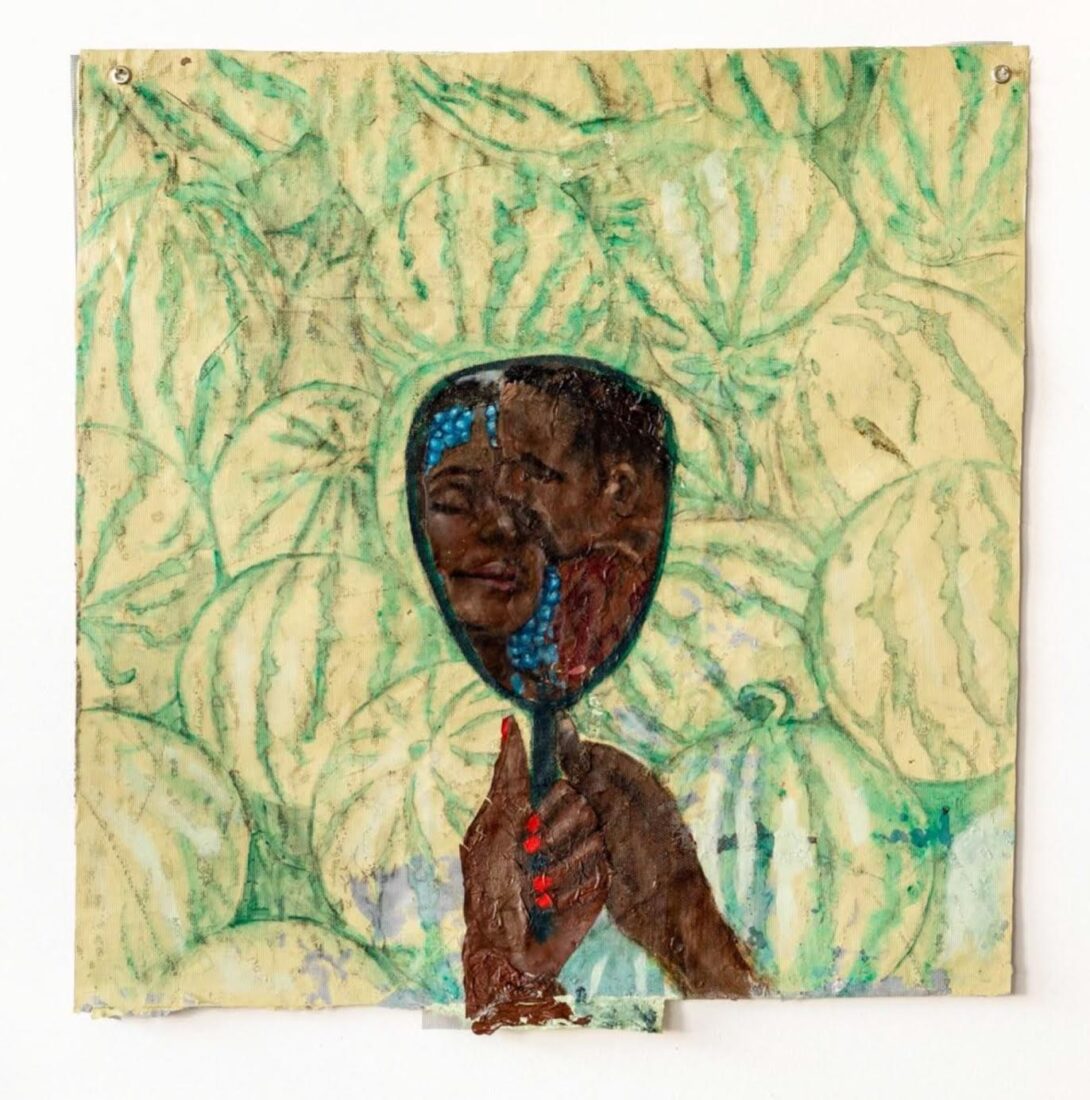

Like his unconventional process, Henriques’s figurative paintings challenge expectations. “I think a lot of the imagery of men that look like me is kind of boxed in in a way that was unnatural and impeded their growth,” Henriques says. Many of his models offer up a reflection of Black joy and peace: In By The Fruits, a man and woman—referenced after Henriques and his own wife—share a tender kiss in a mirror against a background of clustered watermelons. A gardener relaxes in her chair as she tends to her peppers in Milagro with Scotch Bonnet. “In works that have nature or green, I’m really pairing the figure to a natural state,” Henriques says, a nod to the lush landscapes of Georgia and Jamaica. “These figures, these melanated bodies, are natural, beautiful, and intentionally made. They’re in their most natural state, made to thrive.”

Alongside spicy peppers and watermelons, mangoes and sugarcane are also part of Henriques’s oeuvre. “I love all fruits,” he says, though the bright Scotch Bonnet, which he and his wife grow in their own garden, is one of his favorites. Watermelon, which inspired the artist’s multimedia series Watermelon For Chocolate, is a symbol of love, despite its complicated history as a racist symbol after the end of the Civil War and beyond. “I wanted to engage with the fruit through my lens and how I saw watermelon. There’s that particular love, nurture, and care you get when you bite into a watermelon on a hot day,” he says. “History intended to make watermelon a stigma. I wanted to make the work more about freedom and joy. About sustaining yourself with what you have.”