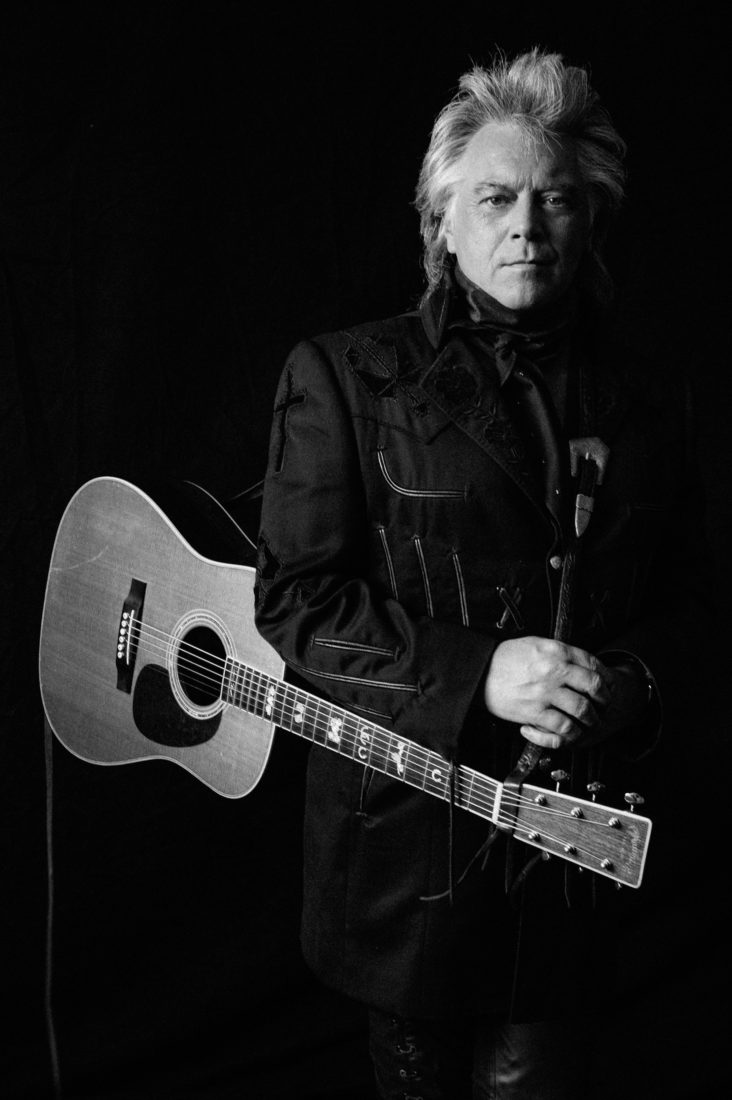

On an early spring morning, Marty Stuart calls in from the most expected of places: His tour bus. Stuart and his ace backing band, the Fabulous Superlatives, are on the road spreading the musical gospel of their spectacular new album, Way Out West. Stuart grew up a Mississippi boy, but the album’s fifteen songs are Stuart’s ode to the American West, with a mix of acid-streaked desert psychedelia, surf-guitar instrumentals, and an Ennio Morricone feel. If you squint real hard, you might see Stuart riding off into the sunset.

Alysse Gafkjen

West only adds to Stuart’s legacy as one of Nashville’s towering musical figures, a rare artist who has resided comfortably in both the commercial and classic lanes of country music. Given that, it might not make sense that Stuart’s greatest work is only just beginning. The Marty Stuart Congress of Country Music is nearing the final stages of planning and fundraising to eventually be built in Stuart’s home town of Philadelphia, Mississippi. Designed to hold concerts, exhibitions, and educational programming, the center will become the permanent resting spot for Stuart’s incredible collection of more than 22,000 pieces of country music memorabilia. “The history of country music is as important as any other art form,” he says.

Stuart and the Fabulous Superlatives hit the road again on Wednesday for a string of dates that includes headlining shows across the across the country as well as a stop at the bluegrass nirvana of Merlefest in Wilkesboro, North Carolina, on April 30. To get you in that Western mood, Garden & Gun is thrilled to catch up with Stuart and premiere an exclusive video of him singing an acoustic version of the album’s “Wait for the Morning.”

You just played the Ryman again, opening for the Steve Miller Band. How many times have you played that room over the years? It’s got to be a lot.

How’s about 43 year’s worth of plays at the Ryman [laughs]. That was actually the first place I ever played in Nashville. I went on stage with Lester Flatt and his band, when I was thirteen.

The Ryman and the Grand Ole Opry, if you’re a Southern boy, is just a way of life. The first night I was in Nashville, I arrived at the Greyhound bus station at about two-thirty in the morning. A friend was supposed to pick me up, but he was late, and I thought maybe I was at the wrong place, so I went around the corner. At the time, the Greyhound station was across the street from the Ryman. When I saw it, it almost drove me to my knees. I mean, I thought, “My God, there it is.” And I had a feeling I’d be behind those doors pretty soon. Sure enough, in two week’s time, Lester Flatt offered me a job [playing mandolin]. And the first time I was on the stage, I had to stand tippy-toe to reach the microphone. It was an awesome experience. Of all the places I play, the Ryman’s home.

And you had already been on the road as a musician the year before you played the Ryman.

When I was twelve, I went out on the road with some folks in south Alabama called The Sullivan Family Gospel Singers. We played bluegrass festivals, camp meeting revivals, some straight concerts, and campaign rallies. I met strange and eccentric people who talked about music for twenty-four hours a day. And people wore cool clothes and wore their hair any way they wanted to and nobody thought it was weird. I got paid a little bit of money for all that, and I thought, “I have found my life.” Well, at the end of the summer, the Sullivan Family dropped me off, and they kept going. I had to go back to school. I felt like I had been dropped by the circus and kicked to the curb. I couldn’t stand it, man. A friend of mine I had met along the way that summer was named Roland White and he played with Lester Flatt’s band. He had made a casual comment, “Well, maybe sometimes you could just ride along with us on our bus and hang out for the weekend.” I got kicked out of school about fifteen minutes into the ninth grade and I called Roland and asked: “Would this be a good time for me to come out?” So, Labor Day weekend, I was on the bus to a show in Delaware.

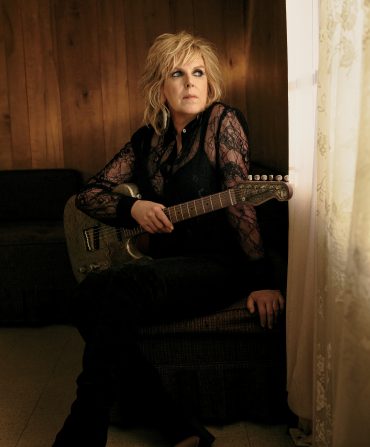

Alysse Gafkjen

What did you do to get kicked out of school?

Well, I was reading a country music song in class in the middle of my history book and I got lost in the story. And the history teacher walked up and knocked it out of my hands. She said, “If you can get your mind off that garbage and get it on the history, you might make something of yourself.” Smart ass here said, “Well, I’d much rather make history than read about it.” So I called Roland and Lester Flatt cleared it. I begged my parents to let me go just for the weekend. It was kind of like The Wizard of Oz. Everything went from black and white, to colored all at one scene. That’s when my life kicked in.

Oh, man. Now parents won’t even let their thirteen-year-olds go around the block. Things have changed.

It never even dawned on me how unique it was until years later when my drummer brought his son on the bus. Travis was his name, and he was sitting over there on the couch, and I said, “Travis, how old are you?” He said “Fourteen.” And I saw myself all of a sudden. I physically almost got sick—looking at that little kid going, “Man, you have no idea.”

Was there something in particular as a kid that triggered your obsession with the American West?

Johnny Cash had a song called “Don’t Take Your Guns to Town” and I was just absolutely enamored with it. It transported me from my bedroom in Mississippi out to the American West. And whether it was that song or the music that was coming out of Southern California, or Steve McQueen in “Wanted Dead or Alive,” or the nudie suits that the country singers wore, it just seemed that everything that was so cool to me came from the West. And our TV was in black and white back then, and when I went out West, and I saw it for the first time in my life, I was like, “Oh man, this is bigger than I ever imagined.” And to this day, when I go out there, I still become a little kid. I’m just enchanted by God’s creation out there.

Did you ever think about moving out there?

I almost did once. In 1979, when Lester Flatt passed away. I found myself as a teenage musician without a job. I had heard there was a possibility for an opening in Bob Dylan’s band, so I had it in my mind to head out there and check it out. But something deep down inside told me at that point in my life: “Man, if you go out there, the way you’re acting, you will probably come home in a body bag.” I was crazy. In the meantime, a job with Johnny Cash opened up around Nashville, so that took care of that. That’s the only time I was ever really tempted go out there—pull up stakes and go try it.

What was your thinking in doing this type of record now?

When I first put the Superlatives together [in 2000], I went to a record store in New York City called Bleecker Bob’s. There was an Ella Fitzgerald box set in there that had a linen cover emblossed with the title, Ella Fitzgerald: The Verve Years. I bought it just because the box was so beautiful. When I got home and I opened it up, there were multiple records in there. It was Ella sings Porgy and Bess, Ella sings with Duke Ellington, Ella sings with Louis Armstrong, just on and on and on. I thought, “This is a wonderful way to live a musical life.” And so when I put the Superlatives together, we tried one last round of “We’re going to be country radio stars.” But then I thought, “Nah, that ain’t right.” So after that, we did a record called Souls’ Chapel, which was inspired by the disappearing Mississippi Delta gospel sound. And then we did Badlands: Ballads of the Lakota. And then there was Live at the Ryman, then The Ghost Train, The Studio B Sessions. So Way Out West is just a continuation of an evolution and a musical journey of a band. Of all the records we’ve done, this one has a little extra spark in it. I wanted to make a really cinematic record. And with the West, you can do that. It takes you back to the core of the human spirit. It’s man against the elements out there. And you don’t have a city to hide in. You’re on your own with your spirit and your heart and your soul.

You recorded the album in Los Angeles with Mike Campbell from Tom Petty’s band, the Heartbreakers. What did he bring to the project?

Campbell is one of my favorite people. I have so much respect for him as a guitar player, as a person, and as an arranger. I knew that this wasn’t a project I could record authentically in Nashville. I needed to go to the West to do it. But we’re both Southern boys and we probably grew up listening to a lot of the same music. If you listen to any song that Tom Petty has ever recorded, you will recognize the guitar part. I had a feeling Mike had a lot to do with the arrangements of some of those songs.

What is the status of your country music center in Mississippi?

We’re about to lock in the location. The board is in place and the architectural renderings have been drawn. The last thing to do is finish raising the funds to bring it to life. It’s probably a three- to five-year process before we have a ribbon-cutting day. But it is absolutely on the way.

When did you get serious about collecting memorabilia?

I started as a kid when bands would come through town. I’d get signed pieces or autographs or ask for guitar picks. But I got really, really serious about it in the 1980s. It just went nuclear from there.

How long before you had to get it out of the house?

It was pretty obvious pretty fast that this was way beyond being in a house. It started in a little warehouse, then a bigger warehouse, and now it’s down in Mississippi in a huge warehouse.