I used to take solitary walks before sunrise—three-mile, one-hour marches that emboldened or pacified me, depending on which way my mental pendulum was swinging. But last year I joined forces with an eleven-year-old Labrador mix who is utterly impervious to changes in mood. His personality rests at one fixed point: exuberant. That’s all he’s got.

Blizzard is strong and blond with brown eyes and kisses of white fur on his face. I am strong and formerly blond with brown eyes and wisps of gray around my face. Blizzard is older in dog years than I am in people years, but neither of us is young. And despite our maturity, we both have some growing up to do.

Technically, Blizzard belongs to my next-door neighbor. He was a present for her daughter when she was a little girl. This was the child who, presumably, gave Blizzard his name. Would anyone over the age of seven name a Texas Gulf Coast puppy—destined to spend most of his days in swampy ninety-degree heat—Blizzard?

Since then, Blizzard has spent most of his life alone in my neighbor’s backyard. Even as a puppy, when his energy was explosive, he was confined to the yard, which meant few human or canine playmates. When he was let out for the occasional walk, he’d tear toward the street with the glazed determination of an inmate who’d finally broken free, running laps around the cul-de-sac and heading full speed toward everyone he encountered. This did not endear him to petless neighbors with young children.

Many, many nights, Blizzard barked for hours. Everyone on the block knew him, and not in a good way. All the while, I remained a silent witness to his lonely life. I didn’t get involved. My husband and I were busy raising our son. We both worked long hours at a newspaper. We had cats.

Years passed, and the daughter moved out, leaving just my neighbor and Blizzard at her four-bedroom house. She works long hours. As soon as Blizzard hears her car pull in the driveway, he hurls his body upright on the back door. “Let me in!” he barks, his wagging tail a series of exclamation points. If it’s really cold or really hot or raining like hell, she obliges. But usually, Blizzard stays outside.

A little more than a year ago, Blizzard started escaping regularly. Our twenty-five-year-old subdivision’s fences—weathered wooden slats that divvy up the suburbs of most of Texas’s big cities—had grown so worn that he was able to chew, dig, or claw his way out. He tended to break free on trash day, which does not strike me as a coincidence. (All. Those. Chicken. Bones.) Neighbors, faced with torn-up trash bags and debris scattered along their curbs, got irritated with him all over again.

My husband and I lay in bed one night and strategized. The next day, we asked our neighbor if we could mend her fence to help keep Blizzard contained. She agreed. Both her mother and her grandmother were sick, she explained, so she was away from home a lot. She said she’d probably have to put Blizzard down if she couldn’t find a way to stop him from escaping.

So my husband and I stacked cinder blocks inside Blizzard’s fence to fill in the gaps. We rebuilt his prison so he wouldn’t be put to sleep.

Then we had an idea: I liked to walk and Blizzard needed walking.

The neighbor agreed to let me try. Now, most mornings in the dark, I pad across the lawn to her side gate and brace myself for the column of energy ready to hit my upper body. Blizzard’s a jumper. “Sit,” I say, holding out a tiny chewy heart. His bottom grazes the ground just long enough to snap up the treat from my fingers, then he shoots past me into the front yard and pees. I let him sniff and run sideways with excitement a few moments more and then, real quick, I wrangle the leash around his neck and we set out into the suburban wilderness, two specks on the edge of Houston’s sprawly glow.

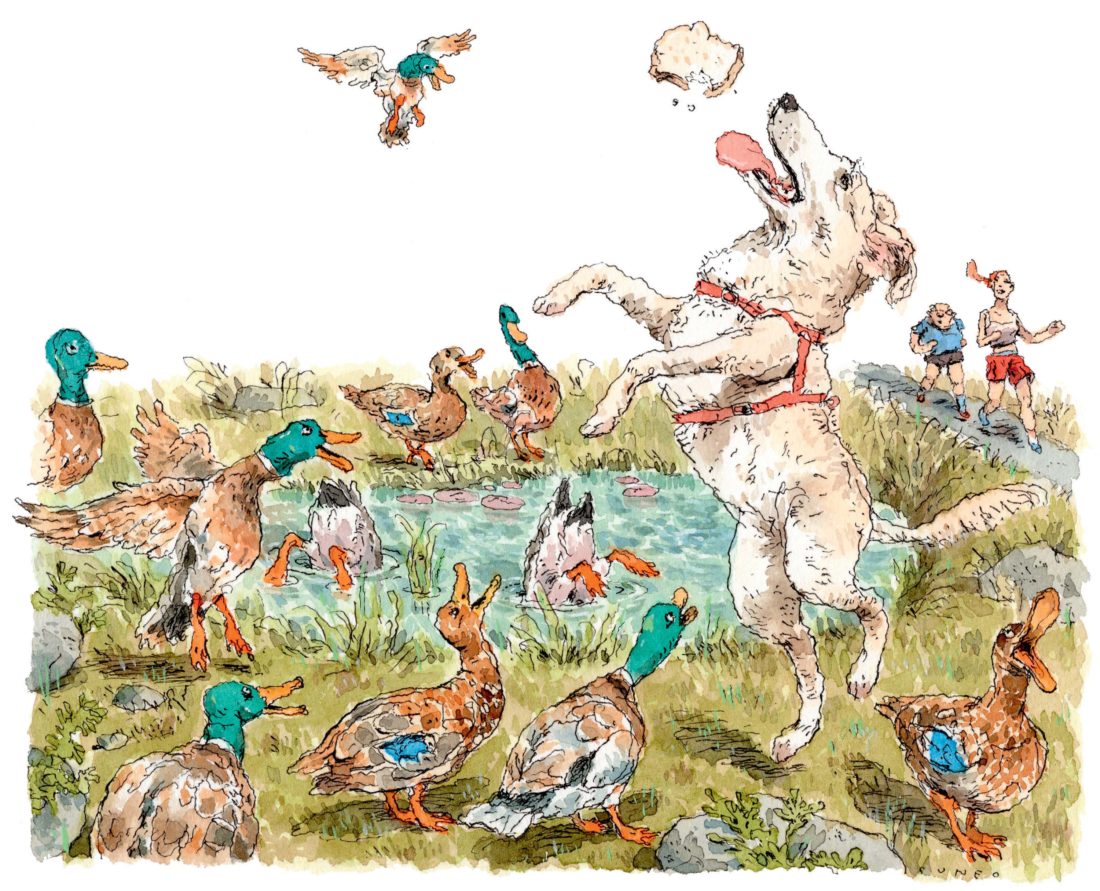

Blizzard is the first dog I’ve ever walked. I’ve always liked dogs, but I didn’t have one as a kid—my dad was allergic—and by the time I got out on my own, the thought of caring for one was intimidating. Then I got cats and never looked back. So I was anxious walking Blizzard, to start. The amount of saliva slipping from his mouth in sloppy strands was shocking and, at forty pounds, he was all I could manage on the leash. But as we continued to walk, first once and then twice a day, he began to relax enough to really enjoy himself. And I began to look forward to his company. It made me happy to see the flash of blond fur between the fence slats each morning before I unlatched the gate. On our walks, I let him linger at rain puddles to lap up the fresh water. I allowed him to eat two full slices of wheat bread in the park—left regularly for the ducks—before I tugged on the leash to lead him away.

Why now? my family and friends asked. Why, after ignoring this dog for a decade, have you become his new best friend? Somehow, our lives collided at just the right time. I need him as much as he needs me, because he is bursting with something I’d lost. Blizzard craves interaction—he’s desperate for it. Other than food, it’s the reason he gets up in the morning. He runs headlong into the world to connect, to share his time on this planet with other living beings. Somehow, I had misplaced this urge. After twenty-five years of reporting for a living, of being paid to be and stay interested in people, my brain was overflowing, a brimming glass of water under a fast-running spigot: New information tried to get in, but most of it ended up spilling down the outside of the glass. Walking Blizzard has helped me clear my head and become more deliberate about how I fill it. I’m teaching him how to pull back, and he’s helping me push forward.

When my husband and I started bringing Blizzard into our home, we quickly learned we had to keep him on a leash or he would trash the place with enthusiasm. We had brief dreams about domesticating and integrating him into a place where two cats—Leo and Phoebe, sturdy siblings who weigh in at eighteen and thirteen pounds, respectively—hold court. Somehow, two felines and one canine could reach an understanding and live happily ever after, right? Hell, no. Blizzard jumps and barks like a madman when he sees the cats, which is why he stays on a leash and they stay on the edge of his sight line—far enough away that he might not notice them but close enough to keep their wary eyes on him. I know what the cats are thinking: Really? Now we’ve got to deal with this damn dog?

Yet Blizzard is learning to better contain himself. We bought him a big crate for sleepovers, and it seems to soothe him. On the evenings he spends with us, he’ll practically lead us to the crate when he’s ready to go down. I think he finally understands that he’s a part of our lives, that we’re not going anywhere. And now that we’re helping her with Blizzard, our next-door neighbor, grateful for our efforts, is free to enjoy him.

Blizzard and I manage two to four miles a stretch these days, around man-made lakes outfitted with fountains, past house models that repeat every few blocks, along streets named for things—Something Glen, Something Hills—that simply do not exist in this part of Texas. Since starting to walk Blizzard, I have found beauty in this landscape. When the reeds shake, we know the ducks have taken cover from passersby. We watch for the turtles that hang out under the bridge and slip noiselessly into the water as soon as they hear our footsteps. When I pick wildflowers from a muddy stretch of land underneath a row of cell towers, Blizzard runs around me in a circle and pants. It’s glorious.

We’ve started to make new people-dog friends, too. We’re especially fond of Marilyn and Coco. “He looks so happy!” Marilyn said when we ran into her on a recent nighttime loop. God, I hope so. Blizzard and I are working on this happiness thing together. He’s the yang to my yin, the enthusiasm to my reticence. Together, we strike just the right balance.