When the film director Olivia Newman poked around Google for early production inspiration for the bestselling book turned-summer blockbuster Where the Crawdads Sing, she stumbled on the Johnson Collection.

The collection and gallery, based out of Spartanburg, South Carolina, houses some of the most iconic and extensive reserves of artwork in the South, lending out pieces across the globe—including to Italy’s Biennale di Venezia. But it was the Charleston painter Alice Ravenel Huger Smith that captured Newman’s attention out of the 1,200-piece collection.

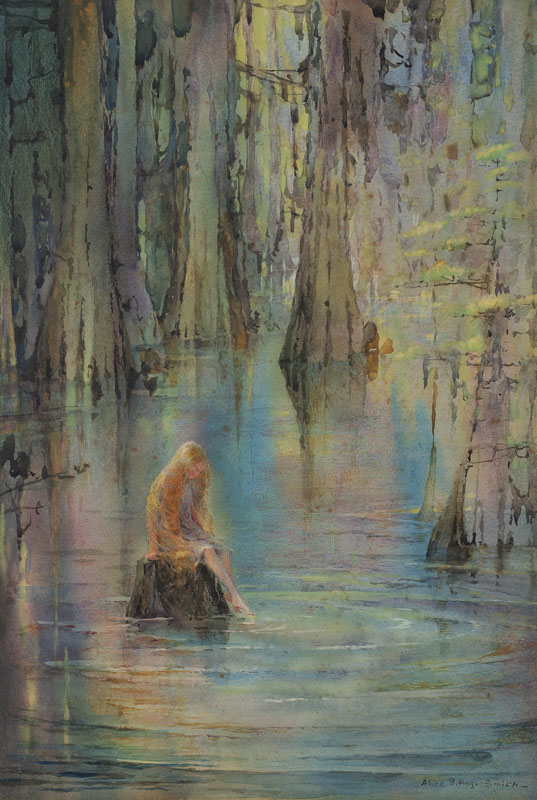

Smith, a prolific nineteenth century watercolorist, was known for her eye in capturing the Lowcountry region: For sixty years as an artist, she tapped into her surroundings, crafting mystical scenes of hazy marshes, cypress wetlands, and shorebirds in flight. “Her work really spoke to Olivia Newman and what she was looking for, especially visualizing the character of Kya [played by Daisy Edgar-Jones] and the landscape of the film,” says Sarah Tignor, the chief operating officer and curator. “Newman told us that the painting At Eutaw Spring was a touchstone image for Kya. To hear that was pretty celebratory for us.”

Smith was a self-taught artist who had only taken a handful of classes as a young woman, but Tignor considers her style nothing short of “jaw-dropping.” Smith deftly worked with watercolor—a deceptively difficult media that requires measured planning, color layering, and patience—to illustrate the mystical quality of coastal Southern landscapes. As a Charleston native who remained in the South for most of her life, Smith devoted herself to her homeplace, becoming an expert on rendering the region.

“She was an artistic catalyst for Charleston and pushed to start the Charleston Etcher’s Club in 1923. The group produced multiple prints for the Historic Charleston foundation and Carolina Art Association, laying the groundwork for the Charleston Renaissance,” Tignor says. “A lot of tourists in Charleston would buy an etching to bring home as a souvenir, celebrating, sharing, and preserving the region’s art.”

When it came to sharing the paintings for the movie, the Johnson Collection worked with Smith’s family members and estate to carefully and accurately photograph and reproduce twenty watercolors for the film set. The Johnson Collection collected high-resolution images for Newman and her team, allowing them to decide the scale of the pieces and paste them around Kya’s cabin set.

The artwork takes on its own role, represented in the film as paintings from Kya’s absent mother. The studio aged and wrinkled the printed reproductions, adding a handmade feel to match the rustic cabin and its assortment of marsh bird feathers and sea shells. Between the New Orleans filming location, the North Carolina literary setting, and the inclusion of a Charleston painter, “there are so many different iconic Southern locations that pull together to a mythical Southern story.”

The film, which was released July 15, came out a day after Smith’s 146th’s birthday. Although the Johnson Collection wasn’t initially certain which of the twenty images would make the final cut, viewers can spot four of Smith’s works—but you’ll have to see the film yourself to see which ones made the big screen. “At the Johnson Collection, our mission is to share. We want to hit viewers with our region’s most iconic mood—the aura of humidity,” Tignor says. “Whether you’re born in the South or you’ve come to paint it, visual art has the ability to evoke that mood. And I much prefer humidity in painting than real life.”