In his 2001 fantasy novel American Gods, the British author Neil Gaiman describes visitors to Rock City—Chattanooga, Tennessee’s most famous non-locomotive attraction—like this: “When they leave, they leave bemused, uncertain of why they came, of what they have seen, of whether they had a good time or not.”

When I first read those lines, I bristled—my standard reaction to anyone daring to describe anything relating to my hometown without first living there for eighteen years—then huffed in grudging recognition.

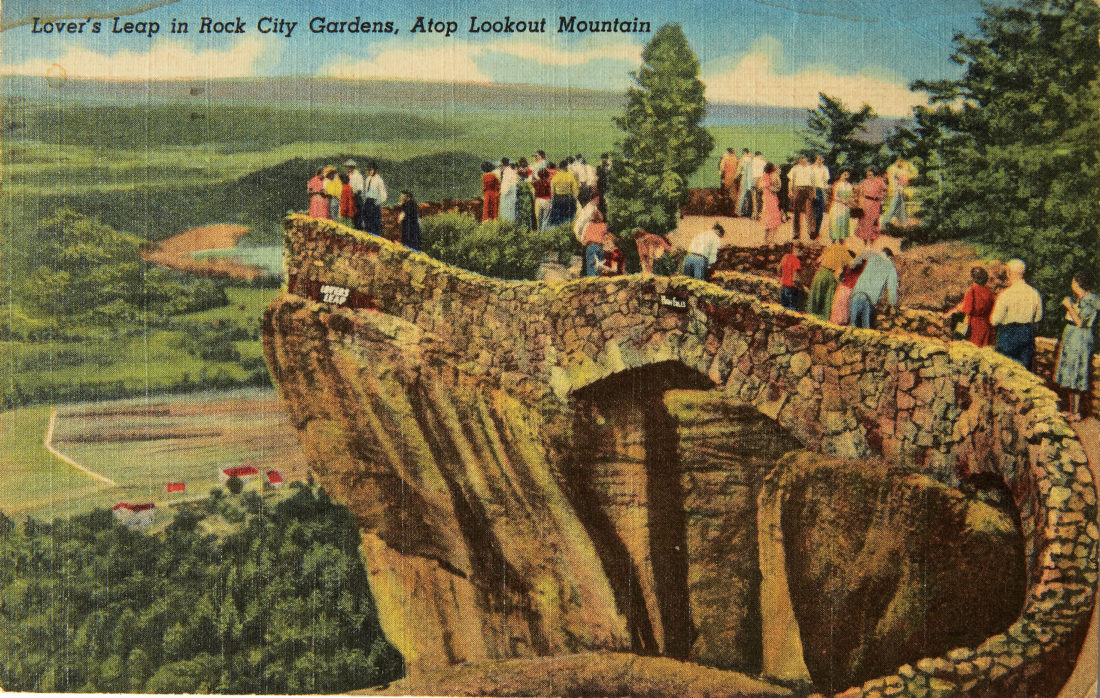

As a kid, I made the pilgrimage up Lookout Mountain to Rock City countless times. With my family, I wandered the narrow paths between boulders and over the suspension bridge to the Lover’s Leap overlook, where I strained to See Seven States and posed for photos with foam-headed mascot Rocky the Elf before descending into the lurid dreamscapes of Fairyland Caverns and Mother Goose Village, a subterranean hallway lined with black-lit dioramas of fairy tales and nursery rhymes. Back then, the place seemed not just entirely natural but eternal to me, without beginning or end. In fact, it had been coaxed into being during the late 1920s by Frieda Carter, an avid horticulturist, lover of European folklore, and wife of a local real estate developer. Frieda designed the trails, augmented the landscape with native plants, and hired a sculptor to build the fairy-tale statuary. Then her husband, Garnet, saw dollar signs. The Carters opened the gardens to the public in 1932 and a few years later paid a man to paint black-and-white ads on barns all the way up to Michigan.

I still mentally salute every see rock city sign I pass along the roadsides of the Southeast—at ease, you weary soldiers of outdoor advertising. A few years ago, I even bought a seen rock city bumper sticker to prove I could lovingly eye-roll like a local despite having lived in Atlanta for a decade. Yet I couldn’t bring myself to slap the sticker on my car. Its claim was true, but I found myself unable to trust my memories of the place. When I poked at them, they squirmed and shifted away. Gaiman’s words buzzed in my head. I knew I’d seen something there, once upon a time, but I could no longer say what it all added up to.

Last August, I used some friends and their tiny kids as an excuse to revisit this childhood mirage and try to get a grip on whatever it was that eluded me. “It is exactly the right amount of cheesy and bizarre, and the views are really beautiful,” I promised. But as we pulled into the parking lot, I got clammy. Naps, feeding schedules, and diaper situations were on the line. If we came out the other side bemused and uncertain—or worse, overtired and hungry and sticky with the sap of a tourist trap—my strange fealty to a handful of gauzy memories would be to blame.

Our posse bought tickets and entered the park through a gift shop stuffed floor to ceiling with birdhouses painted like the famous Rock City barns and lawn gnomes wearing American flag–printed vests. I clenched my teeth. But within moments, we found ourselves walking a trail lined with ferns and rhododendrons cut by nature and time between the mossy walls of hulking sandstone. The humidity dropped precipitously, blessedly. As we navigated one tight passage, my smallest friend, Calvin, strapped to his mother’s chest, rolled back his melon head and grinned at the bright sliver of sky far above.

The path led us through the woods, over and under lichen-flocked footbridges, past assemblages of plaster gnomes working and playing and making moonshine, over an enclosure of fallow deer, all the way to Lover’s Leap with its view of, if not seven states, then at least the rolling green hills and blue haze of Lookout Valley. Rocky the Elf sauntered around the plaza, his old red stocking cap replaced with a jaunty straw boater but his toothless grin as insistent as ever. Kids hugged his knees and grinned for photos, just as I’d done a generation before. My second-smallest friend, Cora, regarded him from a safe distance, her face contorted with repulsion and delight. “I feel you, girl,” I said between mouthfuls of Dippin’ Dots.

We continued down the trail, through Goblins Underpass and Fat Man Squeeze. “So I guess we already went through Fairyland Caverns,” my friend Brooke said after a while, disappointment in her voice. My cackle bounced off the boulders. “No, no,” I said. “You will absolutely know when you’ve gone through Fairyland Caverns.”

And soon enough we were there. A purple-lit stairwell dropped us down, down, down into the earth. Frieda Carter and her sculptor had carved dozens of niches into the rock walls, and each contained a miniature scene from a fairy tale or a nursery rhyme, the figures and sets all painted in colors that pulsed like neon under hidden black lights. Day-Glo Goldilocks ran, in perpetuity, from an oddly muscular trio of Bears; the Three Men in a Tub patiently awaited rescue, knocked back and forth on their same old motorized sea. And around one bend, the route opened wide into a big room with black walls and ceiling receding into infinity, the centerpiece a sprawling landscape: Mother Goose Village. Jack and Jill tumbled along the hill they’d been falling down for decades; vacant-eyed Humpty Dumpty teetered atop his wall, forever on the verge of his own fall; the Dish ran away with the Spoon, and the Cow jumped over the Moon; and Cinderella’s castle glowed above it all, as poised and garish as ever.

My friends kept looking at one another, bug-eyed and laughing. Cora perched on her dad’s hip, mesmerized, the white stars on her pink dress glowing eerie blue. Somehow I’d been that small once, staring from my own parents’ arms at these same strange displays, their oddity barely matching the oddness of my own child mind. All of this had once seemed as natural to me as the boulders and the rhododendrons, and therefore more normal than the whole rest of the world. Here, I realized, was the crux of my confused Rock City memories. Mother Goose Village had once loomed so large in my consciousness that I’d taken to actively downgrading it, overcorrecting for time’s known tendency to inflate and exaggerate. I’d been so certain it would turn out to be small and sad, but it was even bigger and stranger than my original recollections. And it was only here, in the wacky heart of the place, where the air seemed to thin and time to flatten, that I could begin to see what I’d seen here before.

We spilled out of the Caverns laughing and blinking into the sun. “Man oh man,” my friend Austin said, shaking his head. “You really undersold this place. It’s so weird and great.” Cora’s wide eyes were still fixed on the dark hole from which we’d just emerged. In thirty-something years, I wondered, would she return with her own children and her own foggy memories of the place, bracing herself for disappointment and instead finding firm reassurance that you actually can go home again, so long as home is this one particular Depression-era tourist trap? For one dreamy moment, I knew the answer was yes.

I rode the high of my relief all the way to the end of the path, which deposited us back at the gift shop. Among the bric-a-brac emblazoned with the park’s signature demand, I found a Christmas ornament designed to look like one of the Rock City birdhouses designed to look like the Rock City barns. The ideal souvenir for this place—a thing that was and wasn’t a series of even more familiar things. I plucked one from the display, paid for it, and slipped it into my bag on the way to the car, already beginning to forget whatever it was I thought I knew about wherever it was I thought I’d just been. Same as it ever was, same as it should always be.