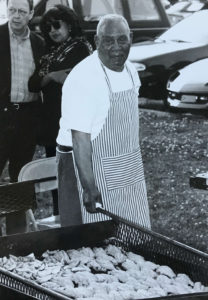

At the Southern Foodways Alliance’s first symposium in 1998, Ed Scott Jr. accidentally set the lawn on fire while frying catfish for the crowd. No one was harmed, but the incident, near an Ole Miss administrative building, became legend and so did Scott. He is believed to be the first African-American catfish farmer in the Mississippi Delta, had served with General Patton in World War II, and helped prove that the USDA was discriminating against black farmers. When Scott died in October 2015, he was honored and buried during that year’s SFA symposium. In 2018, Pond Fresh, a book about Scott’s life and accomplishments by Julian Rankin, will be published by the University of Georgia Press.

Photo: Courtesy of the Southern Foodways Alliance

Ed Scott Jr. in 1998

Incredible stories such as Scott’s are a hallmark of the Southern Foodways Alliance, the University of Mississippi-based non-profit organization dedicated to documenting and celebrating the ever-changing food culture of the South. This weekend, the SFA will host its twentieth annual symposium, highlighting Latin American influences in the South and showing how far the region has come since that first gathering when its director, John T. Edge, was a graduate student at the Center for the Study of Southern Culture at the University of Mississippi. Inspired by pioneering conferences he’d attended on Faulkner and Elvis, Edge began to toy with the concept of doing the same for Southern food. “The first symposium was a gathering of the tribe,” says Edge, who is a contributor to G&G. “It was people who were interested in the same things and saw the possibilities of what could be done with it.”

Each following year as the symposium focused on different aspects of Southern food culture, the organization broadened its reach, adding more staff and accumulating more members. “As we grow in strength, we grow in the strength of our storytelling,” Edge says.

Photo: Courtesy of the Southern Foodways Alliance | Brandall Atkinson Photography

A plate served at the 2014 symposium.

Through its combination of scholarship, documentaries, oral histories, and events, the SFA has championed restaurants like Doe’s Eat Place in Greenville, Mississippi; The Bright Star in Bessemer, Alabama; Crook’s Corner in Chapel Hill, North Carolina; Hansen’s Sno-Bliz in New Orleans; and Bully’s Restaurant in Jackson, Mississippi, long before they received James Beard America’s Classics Awards. Similarly, award-winning chefs like Sean Brock, John Currence, and Leah Chase worked with the SFA before they rose to national acclaim.

Although the SFA is on the forefront of Southern food culture, that’s not necessarily its priority. “The caliber of the food is important, but for the most part, our programming focuses on working-class artisans, farmers, and cooks. We really have no interest in what the next trend will be,” says Edge. Instead, the SFA finds ways to tell new, hidden, or previously overlooked stories—which may well become trends of their own. “For this region to flourish, endure, and progress, we need to come up with new narratives, new heroes,” says Edge. “The future of Southern food will no longer be about where our food comes from, but instead, who our food comes from.”

Despite the changing nature of Southern food, Edge’s favorite dish remains a basic one. “Greens,” he says. “Collards, mustards, turnips—in that order. It’s just so elemental, so straightforward, so sustaining.”

Whether it’s covering the elemental quality of greens, the communal nature of barbeque, or the inclusivity of pozole, here’s to twenty years of the SFA—and hopefully, twenty more. After all, the organization doesn’t just tell stories about catfish, but rather catfish, like Ed Scott’s, that have the ability to set Southern culture on fire.

The Southern Foodways Symposium is October 5-7 in and around Oxford, Mississippi. Tickets are not available to the public, but presentations will be streamed live online. See southernfoodways.org and follow @potlikker on Twitter for more.