Just before my daughter’s second birthday, she began requesting bedtime stories. My wife and I had always read books to her, but now she wanted tales of my own creation. I’m a writer. I can do this, I thought. Over the next few nights, I gamely generated a good one about a kitten lost in the snow, then another about our neighbor’s dog sailing a boat. But soon I started drawing blanks. Finally one night, a couple of days later, at a loss beside my daughter’s crib, I said, “Once upon a time there was a dog named Annie.” And that’s when it all began.

You get only one first dog. Yes, you can have dogs all your life, but those that share your childhood loom with extra import over all subsequent years. My very first dog, a sheepdog named Shadrack, was old when I was born and died by the time I was three. I have no memories of him, so he doesn’t really count. But Annie, Annie was the dog, the dog of my youth.

The first Annie story I told my daughter was the creation myth. It goes like this.

In 1982 I was a five-year-old kindergartner in Greensboro, North Carolina. One lunch period an emaciated black-and-white puppy loped out of some scrub pines and into the playground. Apparently constructed out of little more than bones and questionable border collie genes, the dog knew she had just struck gold. (Gold, in this case, meant a bounty of peanut butter and jelly sandwiches provided by me and my friend Ralph.) We fed her for about a week before my mother caught wind of the situation and put the dog in the car with the rest of us when she picked up carpool one afternoon. The thing was so sickly that before we even got home, Mom stopped at the vet and left her with Dr. Ken Eiler, ostensibly with the idea that he would put the emaciated dog to sleep.

Three days later, the vet called the house.

“Pam,” he said, “come get your puppy. She’s firing on all six cylinders now.”

What was a mom to do? Against all odds the creature was still alive, coaxed back to life by the miraculous Dr. Eiler. So we picked her up. If a starving animal can look brand new, this dog did. Her fur suddenly shone and smelled of clinical shampoo, but she was still lanky and bony, just a cleaned-up hungry puppy. She was a gentle girl, though, polite even in her need. My brother announced, “This is the best free dog we ever had!” not knowing that Mom had just footed a $350 vet bill. Mom suggested we name the dog after Little Orphan Annie. And so it was.

At home we filled Shadrack’s old dog food bowl with kibble, and Annie ate until she fell asleep with her head in the bowl itself, as if guarding the meal at all costs, not sure she’d ever have another.

I guessed my daughter would cotton to the image of a dog asleep in a food bowl, and I was right. After I finished the story, she requested it again. She requested it the next night. Soon she wanted more, and so I told others.

I told her about how, one day, when driving home in our huge silver Dodge Prospector, my mother took a sharp turn onto Country Club Drive, and Annie, who was sitting in the passenger seat enjoying some fresh air across the tongue, fell out the open window. Mom didn’t even notice until a few houses later when she looked over, found the seat empty, then turned to discover Annie stunned in the street behind us. I told her how, for my school’s annual fall festival, I dressed Annie as a Mexican bandito and entered her in the Halloween costume contest. I told of the Christmas chocolate incident of 1985, of Annie’s predilection for chewing felt-tip pens into shreds on the dining room carpet, of walks around the neighborhood, of tennis ball catch, of countless dog minutiae.

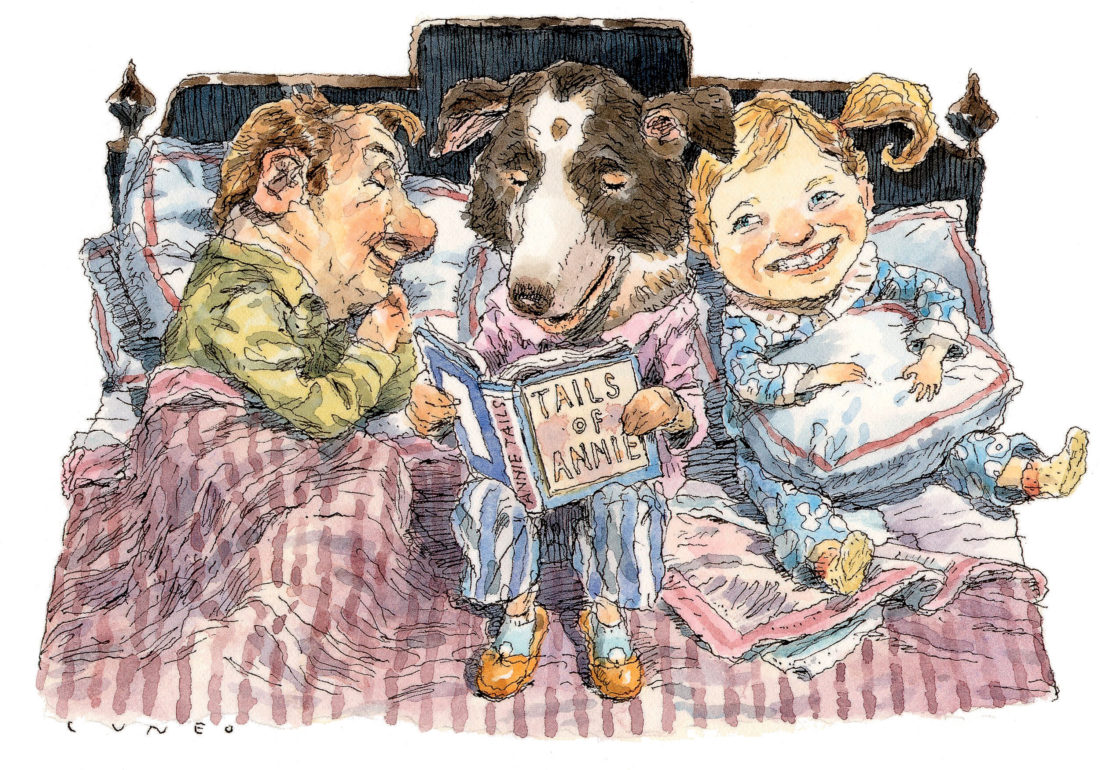

The requests for stories became constant. “Tell me an Annie ’tory!” my daughter would chirp, the s disappearing somewhere inside her tiny mouth.

I told all I knew, but after a month or so, I started to run out of memories. Though Annie was always part of my daily existence, like some benevolent childhood atmosphere, not every day of my childhood generated a story worth remembering, let alone retelling. I recalled the coarse skin on Annie’s back where she always chewed off her hair, her black gums, those dark splotches laid out across her belly like islands on a map, but it’s hard work turning a splotchy belly and a dog’s bald spot into good bedtime stories. So I started making them up.

First it was Annie entering our neighbor’s house in an effort to steal food. Then Annie’s friends, Happy and Molly, began to appear. Soon they all started to talk. The stories became wild, ridiculous, filled with magic and neighbors.

“Annie ’tory!” my daughter would say, every night, and off I’d go.

Requests soon left the bedroom and entered the rest of the house, coming at all times of the day. For the first time in years I found myself thinking about Annie constantly. I don’t have a sophisticated belief system about afterlife, but one night while washing dishes I had the epiphany that, at that moment, Annie was one of the most important things in my daughter’s life. It was a resurrection, a piece of my childhood I was magically sharing with her.

This went on, I kid you not, for almost two years straight. That’s half of my daughter’s life thus far. But recently, her obsession with Annie began to subside. Requests receded once more to the bedroom just before sleep. And then, a few weeks back, she asked for a story about her doll instead. Despite the fact that I had so often rolled my eyes at the requests for Annie stories and longed for them to cease, I now found myself hoping my daughter would ask for another. But she did not. I felt like Annie had died a second death.

I grew adept at telling doll stories in place of Annie ones, and they put my daughter to sleep just as well. But the other night the pattern changed again. We’d kept her up too late (9:00 p.m.!), and so, as any parent knows, an emotional meltdown ensued. I read books to her, told a doll story, but all to no avail. There was nothing that would soothe her. In tears, overwhelmed with fatigue, she finally sighed and said, “Tell me an Annie ’tory.” And suddenly Annie was back, running through the streets again, talking to owls, swimming with mermaids, flying through a thunderstorm. My daughter fell silent, comforted by the image of that other love of my life, eyes closing, and gone.

We don’t have a dog in our family these days, but my wife just told me that the shelter in Oxford, Mississippi, where we moved only weeks ago, houses more dogs than any other town’s in which we’ve lived. Maybe it’s time we went down there and adopted one, if only so my daughter can generate her own stories someday, when, at a loss beside a crib one night, she finds herself mining memories for tales to lull her child to sleep. Because she’s already learned that when you find the right story, one about something you really love, people want to listen. And sometimes, when the story is about the thing you loved most, the people listening close their eyes and start to dream.