Like warm hospitality and backhanded compliments, a love for outdoor leisure has always seemed to me to make a person more “Southern.” If you drop a line in the creek or off the back of a Boston Whaler, you get Southern street cred. A lifelong, casual relationship with golf or tennis tells me you are textbook Southern country club. Hunting makes you legit, too. And hunting with a bird dog you’ve trained? That means you’re the quintessence of the Southern sportsman (by my measures at least).

While I fully believe that planned activities outdoors, especially in the woods or on the water, help define Southern culture, I didn’t come to this conclusion during catnaps in a deer stand or at the watercooler mid–tennis match. Like so many other facets of my identity, my relationship with leisure was shaped by the trappings of my family—a country bunch who in this respect were anything but country. When they did half-heartedly dabble over the decades, the Howard way, their attempts inevitably crashed to earth.

That awkward lurch is framed on all sides by my dad. Perhaps that’s because John Currin Howard’s position on leisure mirrors a born-again Christian’s feelings about Satan: Hunting, fishing, and the desire to be huddled around or floating on top of a body of water are devilish distractions that make weekends, those long, unproductive periods of slowed progress on the farm, wearisome. Best I can tell, JCH, who is now eighty, has never held a golf club, has never caught a fish, and has never joined a hunting group or any group, now that I think about it. When I was growing up, this bothered me. The usual farm extracurriculars for kids—4-H, the annual livestock show and sale, barning tobacco—did not trip my trigger. I was jealous of the camouflage kids in elementary school, their love for ducks and deer advertised all over their sleeves. I hated how pious my family appeared, at church every Sunday, even the summer ones, when all the sinners followed Satan to boat on the river or camp at the beach.

Shortly before I was born, my parents did make a leap toward a life of outdoor leisure when they installed an eight-foot-deep in-ground pool behind our house—an interesting step for two people who couldn’t swim. My dad said he intended the pool to squelch the family’s desire to gallivant. Whatever the reason, I’m glad they did it, and did it in the eighties when it was still acceptable for kids to swim unattended, miles from anyone who could jump in and save them. It was in that pool I won my first gold medal in diving. It’s where I taught synchronized swimming to imaginary students and where I acted out my own terrifying run-ins with the shark from Jaws. Twenty years later, still unable to swim, my parents filled the pool with dirt and planted turnips.

A midlife crisis fueled our next clumsy stab at Southern recreation. At fifty, Dad imagined that his love for driving on land might translate to a love of driving on water, and the Howards became the unlikely owners of one-third of a ski boat. I was especially thrilled. I just knew weekends on the water would baptize our family into born-again outdoor enthusiasts. We tried all the things people do—fishing, skiing, kneeboarding, tubing—but couldn’t quite clear the hurdle of operating the boat properly. There was the time we called 911 as our vessel filled with water mere yards from the dock; something about a plug we didn’t plug. Then there was the day a bee stung my pregnant sister in the eye on the Intracoastal Waterway. Her face ballooned. We panicked and for reasons no one to this day will admit to, we ran out of gas and had to be towed to shore.

When all was said and done, our eager family of landlubbers burned up three motors in two years, with one of them bursting into flames as we attempted to “land” on a party island crowded with boats. What did we learn? No matter how powerful your engine, boats can’t plow through sandbars at full speed. “Giving it a little gas” will not “loosen us up.” A boat is not a four-wheeler. Dad also learned that outdoor hobbies are about more than just the activity itself. Boating, maybe bodies of water in general, didn’t speak to him, but planning, showcasing, and bragging about boating pumped him with new endorphins that left him with a taste for more.

I’m the baby of the family by a lot, and as with all babies by a lot, it is my responsibility, my birthright, to point out and correct the shortcomings of my more seasoned yet less enlightened brethren. I took Beginners’ Tennis in college with dreams of doubles matches in my future. But my classmates showed up with their own rackets and backhands to spare, and I came to realize that phys ed in college is not about learning to do something new as much as it is about scooting through on something you can already do. The next semester, I signed up for Fitness Walking.

When I had children, I vowed to give them all the exposure to outdoor sports a depraved parent could imagine. I shoved rackets in their hands, snapped skis on their feet, and paid guides to tie flies and do all the other technical stuff necessary to make my kids comfortable in their sporting skin. So far nothing has stuck. Next summer is surf camp.

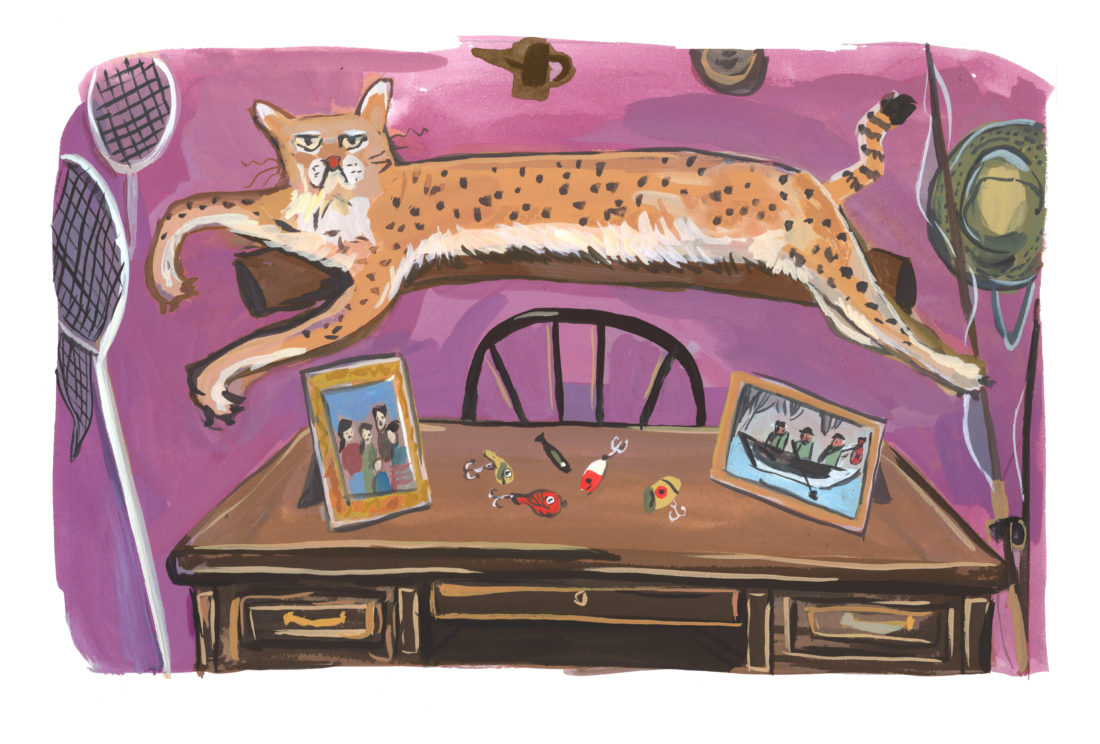

My father, meanwhile, continued his quest to find his inner outdoorsman on a hunting trip to Alabama. Invited by bona fide card-carrying rifle slingers, Dad approached the outing like it was an opportunity he’d be a fool to ignore. These guys, he promised, would make sure he “caught” something, and most important, they would guarantee that his first foray into the woods with a gun didn’t end like his boat motor: in flames. I’m not sure what they were hunting for or if Dad made it into the woods at all. What I do know is that shortly after his trip, he hung a stuffed bobcat above his desk and invited everyone he knew to take a gander at his prey.

In case you’re thinking this encounter with a large wildcat peeled back my dad’s final pragmatic layer to reveal a Southern outdoorsman of unmatched prowess—a mature, gun-toting, duck-slaying prodigy—it did not. The man that emerged instead took on a mission to collect stuffed animals. A white swan with a five-foot wingspan, a wild boar straddling a log, bears, deer, another big cat—these became the trophies of a man who made a deal with a taxidermist to buy anything mounted but never paid for.