I packed my hospital bag weeks before my first child was born.

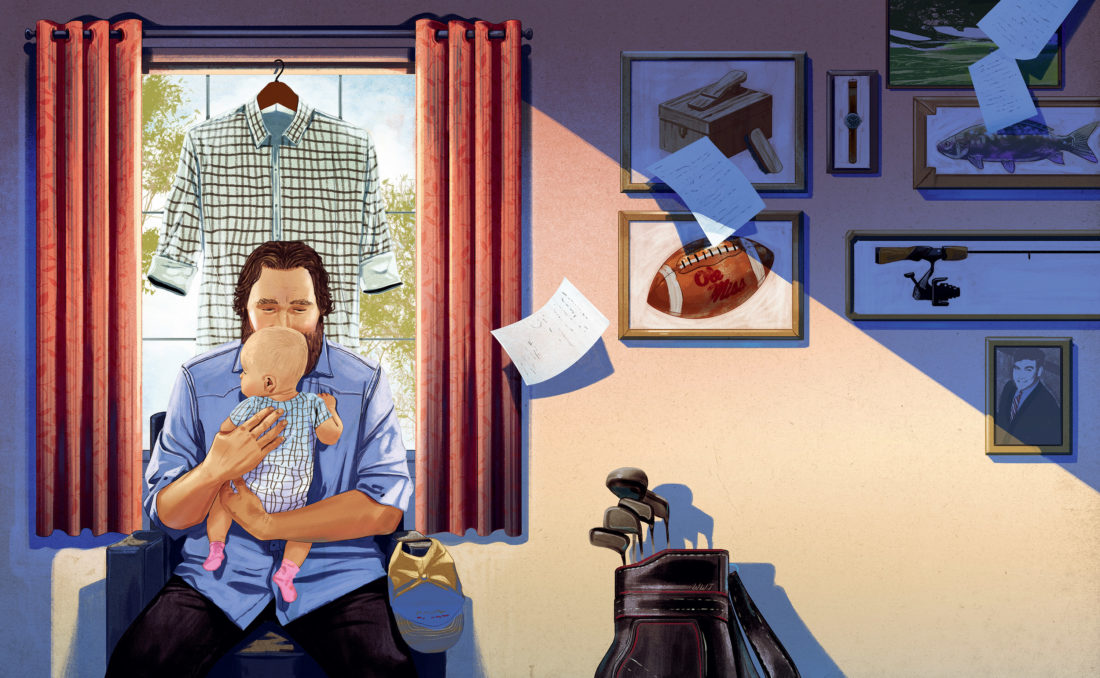

Jonathan Bartlett

Soon-to-be new dads are easily spotted in a crowd: They are the ones who look terrified and still think planning can somehow ease that existential terror. Before zipping the bag and leaving it beside the bed, I threw in an old black-and-white button-down shirt that belonged to my late father, and a Phi Delta Theta Dad’s Weekend hat I gave him and later found in his things. He died thirteen years ago, and having a piece of him in the room as his first grandchild came into the world felt important. His name was Walter Wright Thompson, same as me, and both of us are known to our friends as WWT. Although my wife, Sonia, and I kept it secret to avoid opinions we didn’t want to hear, we had already decided to name our daughter Wallace Wright Thompson. We hope she’ll come to understand what those initials mean.

Sonia’s water broke on a Sunday morning in January. I jumped out of bed and loaded the car with our prepacked bags, ready to make the short yet now daunting drive across a sleepy Oxford, Mississippi, which would soon be Wallace’s hometown. Daddy’s shirt and hat came with us. I’m overly sentimental about things that once belonged to him. Because he didn’t live to see my adult life unfold, these talismans have taken on outsize and somewhat embarrassing importance. His old shoe-shine kit is framed and hangs above the door to my office, and near my desk is a print he once had in his own office: WHEN YOUR WORK SPEAKS FOR ITSELF, DON’T INTERRUPT. I wear his watch and cook with his recipes and drink from his decanters. He wrote me a lot of letters, which I still have in a box. Years later, I’m still trying to make peace with his absence.

I’ve promised myself that I’d stop writing about him. And yet here we are. Sitting in an Oxford coffee shop with my eyes closed, I try to hold a picture of him in my head, and I begin to cry. It’s ten in the morning and I’m crying in public. At least I have the self-respect to accurately feel like an idiot. The memories are coming fast now. The things we once did together feel like flickering dispatches from another life: the trout-fishing trip to Gaston’s resort in Arkansas, watching the Masters, the way he took me to the Grove every Saturday of my early life, and how every single time I go now, I whisper to myself, before pouring a drink and fixing a plate, “We do this in remembrance of you.” He loved Ole Miss specifically, and all sports in general, and he died before I got my job at ESPN. I’ve tried my best to bring him along on the journey, to make sure he never gets forgotten. That’s the least I can do with this enormous megaphone.

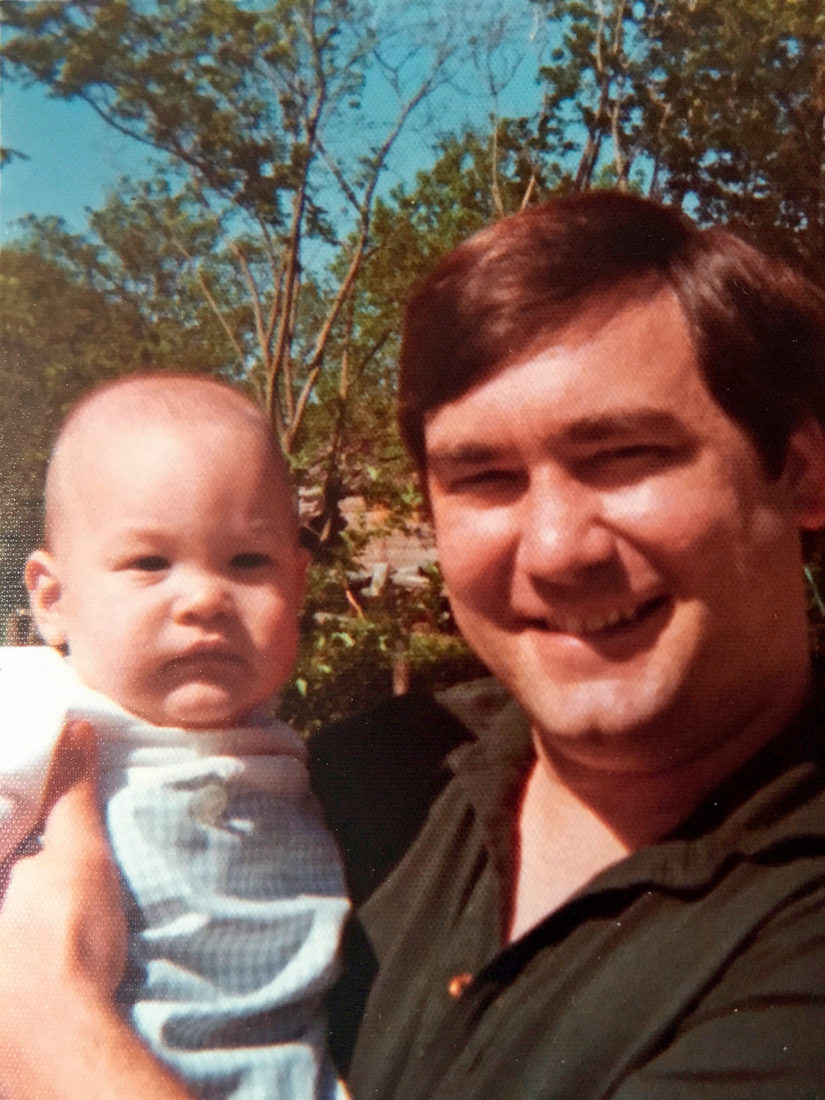

Photo: Courtesy of the Author

Walter Wright Thompson, Sr.—

pictured here with his namesake, Wright—died of cancer in 2004 at age fifty-eight.

Sometimes I think I’m wallowing and Daddy would be disappointed that I can’t look forward all the time. When Sonia got pregnant, I thought a lot about what advice I needed. What knowledge could he pass on? What insight might he have about the inherited sins passed on to me, which I was about to pass on to Wallace?

What had he learned from looking at his and my life?

I wanted a father.

I had a shirt and a hat.

During that long night at the hospital, I held Sonia’s hand. I counted the seconds of contractions. I didn’t think about my dad or the past or the future or anything other than the reality of this room. No other room mattered. In the morning, the nurses told us it was time. I slipped on Daddy’s shirt and hat. I stood by the bed. Sonia felt nervous and wanted to see pictures of the beach and the ocean. After finding the best ones on my phone, she asked if I’d sing her a song. So I sang Jimmy Buffett’s “Tin Cup Chalice,” which always re-

minds us of lazy days in the sun. That seemed to work. The labor passed quickly, and Wallace was born on a chilly Monday, January 15, 2018. (If you’re like my dad and me and prefer your birth dates translated into the ancient and powerful language of Ole Miss Quarterback, that’s John Fourcade, Glynn Griffing, Archie Manning.)

We packed up three days later to go home.

As we pulled out onto South Lamar Boulevard, the radio played the SiriusXM Elvis channel. That made me smile, and I looked back at the car seat holding Wallace.

“This is music,” I told her.

When we drove around the Oxford town square for the first time, I told her that this was her home, and that we were her mama and daddy. It felt good, now firmly and forever looking forward. Right now called for so much energy and attention that I finally felt free of the past. Or rather, I didn’t even stop to consider a past, because of what this new human being in the backseat required of me. We were all in this emerging reality together, Sonia and Wallace and me. I felt confident and calm, as if somehow I’d been carefully taught how to react in this moment. That’s my real inheritance, not some leftover clothes.

A few weeks later, I went out on the road for my first work trip since Wallace’s birth, to Japan for a story on a baseball player. In Kyoto, I visited the cookware shop of a 458-year-old knife maker. In a case by the door were two shiny hammered beer cups made of aluminum. I bought them and had them engraved “SWT” and “WWT.” Maybe Wallace will carry one to the hospital when her first child is born, foolishly thinking that her parents exist in hand-me-down objects. She doesn’t know what I know now: There’s no place she can ever go where I won’t be with her, part of her, which is something my father surely felt about me but I never understood. I didn’t need a shirt and a hat for my father to be present at her birth. He’s always with me and now always with Wallace. That’s how the circle works. That’s the candle in the window, the fire on the horizon. That’s family. That’s god. That’s home.

I thought these things while I held the metal cups in my hand.

The saleswoman asked if I’d like to upgrade to a higher-quality copper version. It wasn’t that much more expensive. I smiled and shook my head. These simple ones that looked like tin cup chalices would work just fine.