Arts & Culture

Finding the Forgotten

In an overgrown and all but lost African American cemetery in Richmond, a group of dedicated volunteers are trying to reclaim a buried history

For some odd reason, I keep thinking of William Faulkner’s Intruder in the Dust. The classic novel is best remembered for the scene in which a Black man and a white man dig up a body in order to clear another man jailed for murder. And though race, the dead, the South, and crime are all involved in the story of Richmond’s historic Evergreen Cemetery, the scene this morning is in many ways the complete opposite of Faulkner’s whodunit. Now the dead remain underground, and Black and white folk are collaborating in the sunshine to clear and honor their resting places. A century ago Evergreen was the premier burial place for African Americans in Richmond. But the sixty-acre site has been severely neglected for decades. Attempts to reclaim it from the forest have started and stopped for more than thirty years. Today is the first concerted effort in three years, and it is remarkable to see how swiftly a forest can retake a graveyard.

It’s Saturday, bright and early. A line of cars lead the way, and at the entrance to Evergreen, a silver-haired woman stands behind a folding table, taking names. Three men hang up a long banner—MAGGIE L. WALKER HIGH SCHOOL CLASS OF 1967 (an all-Black school at the time)—and smile for pictures. Marvin Harris, a member of that class and the lead Volunteer Cleanup Coordinator for this formidable project, greets me. He is a powerfully built man with hands as strong as wire cables. In the distance: chain saws, lawn mowers, the sounds of chopping, cutting. People calling out to one another. About forty people have gathered, and all are at work.

A Richmond native, Harris is the owner and CEO of Harris Group Promotions and Supply, an industrial supply company in the city. Eight years ago he read an article in the local paper about Evergreen and other African American cemeteries in Richmond. He called a friend who had a relative buried here, and scheduled twelve people to come help. Only four showed up. “It was quite a situation,” Harris says. This initial effort led to more and more investment of time, and sweat, and outreach for help. “Somebody had to step up to the plate,” he continues. “If we handle this as a community, we can get it back to the glory days.”

The forest is dense and thick and reminds me of the woods I roamed as a boy. But this density was once a place for families to come honor their dead in pastoral reverence and green splendor. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, having picnics in cemeteries was not uncommon for most Americans. Save for the marble markers now poking up periodically—choked by weeds, surrounded by tall grass, or swallowed by ivy—one might never realize we’re in the midst of a graveyard.

II.

This part of the city east of I-95 is distinctly suburban, the towers of Richmond receding in the distance. A multitude of cemeteries dot the landscape, decorously. Most are well manicured and unassuming. Hollywood—near the center of town, on the banks of the James River—is where the high and mighty ultimately come to rest. Presidents Monroe and Tyler and Confederate president Jefferson Davis are buried there. Following Reconstruction, four African American cemeteries were established in this eastern section of town, in light of Jim Crow segregation: East End, Colored Pauper’s Cemetery, Woodland Cemetery, and the largest, Evergreen. Established in 1891, Evergreen was meant to be the dark mirror of Hollywood.

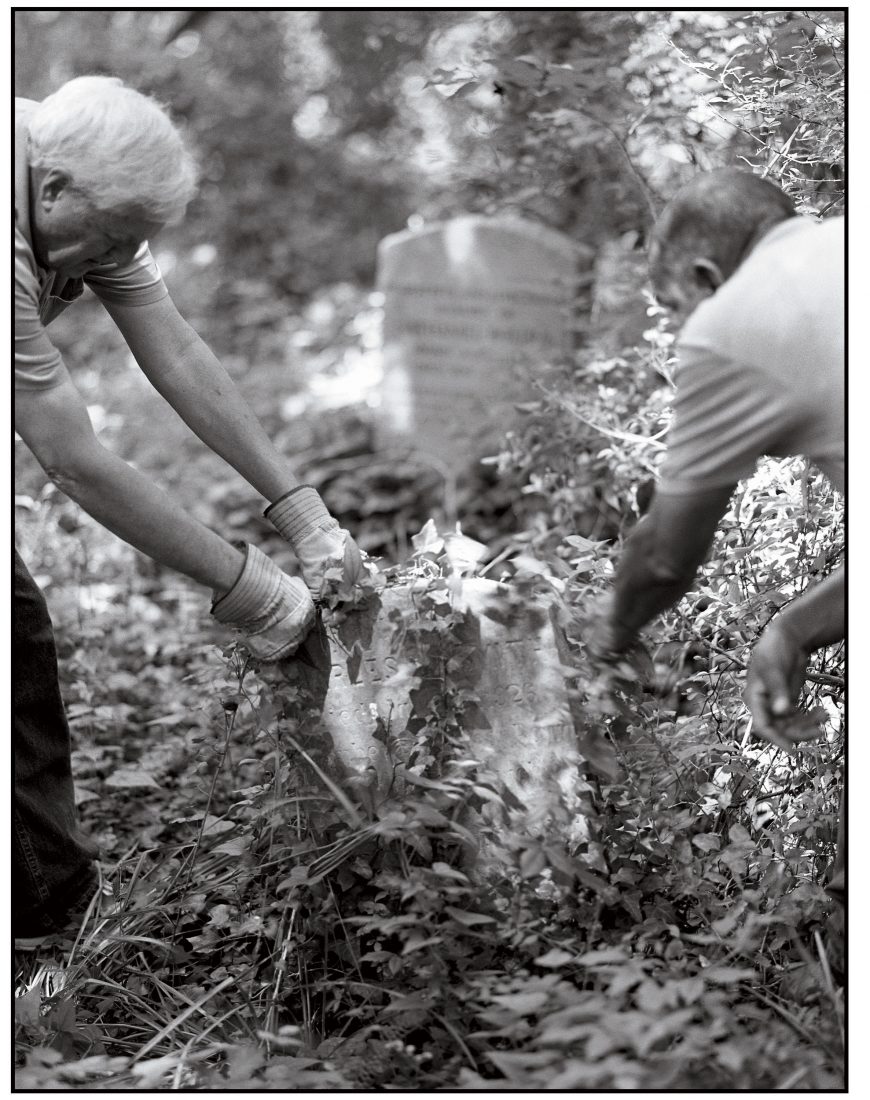

Photo: Michael JN Bowles

Stone Work

John Shuck (Left) and Marvin Harris strip English ivy from a grave marker in Evergreen.

Of all the bustling cities of the American South during the Jim Crow era, Richmond laid claim to one of the nation’s largest Black middle classes. As a result they had the means to memorialize their dead grandly.

The most commanding grave marker stands in the central section of Evergreen, a marble cross about ten feet tall. It rests over Maggie L. Walker, the first woman (of any color) to establish and become president of a bank in the United States. In 1903, she successfully chartered the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank. This led to a merger with two other banks to form the Consolidated Bank and Trust Company, which became a significant institution for African Americans in Richmond. Walker was also a teacher and a leader in education and women’s rights. Many organizations throughout Richmond and the rest of Virginia have been named after her, and her home has become a National Historic Site. Until this morning her grave and monument had been engulfed in impassable brush, hard to find, even harder to reach. But already volunteers have cleared the immediate area surrounding it, the grave and marker now free and clear, along with dozens of others.

Photo: Michael JN Bowles

Hidden Past

Tombstones lie obscured amid the brush and undergrowth at Evergreen Cemetery.

Not too far from Walker are the graves of John Mitchell, Jr., and his mother. Mitchell was a bank president, and the editor and publisher of the Richmond Planet, a leading voice against lynching at the turn of the twentieth century. He unsuccessfully ran for governor of Virginia in 1921.

For more than thirty years African Americans were interred here, the prominent—eminent ministers, doctors, lawyers, successful businessmen, and their families—and the not-so-prominent. But something went sadly wrong. Neglect set in sometime after the Crash of 1929 and the onset of the Great Depression. Burials continued for a while, but the graveyard slowly disappeared into the forest. Nobody knows exactly how many people are buried here. Some estimates run as high as sixty thousand graves in Evergreen alone.

III.

John Shuck is originally from Iowa. A farm boy, He has lived in Virginia since 2001 and over the years has taken the lead in many ways in reclaiming much of the smaller, neighboring East End Cemetery. (He estimates East End, at sixteen acres, is now approximately 25 percent cleared.) Now he coordinates volunteer work for the reclamation of both Evergreen and East End, and most Saturday mornings you can find him cutting brush, raking, pointing out resting places of note.

Shuck is tall and professorial, with the mien of a museum docent, and a touch of Indiana Jones with his wide-brimmed floppy explorer’s hat. No cemetery records for Evergreen exist prior to 1929, he tells me. “So there are no existing records of who is buried here, or where.” He had been a graveyard hobbyist, photographing tombstones and researching genealogies, when he first heard about the cemeteries and came out to photograph in June 2008. He had never seen a cemetery that looked like this. “I thought it might be interesting to clear a plot or two, and that was eight years ago,” he says. “Investigating the history of these people helped me learn the history of Richmond.” Shuck and his team of volunteers recently uncovered their two thousandth grave marker at East End. He posts photos of the markers online so that family members can find them.

Photo: Michael JN Bowles

A newly uncovered headstone near the Maggie Walker grave.

Shuck leads me to a particularly heartbreaking monument in Evergreen. It lies away from the central area the workers have been clearing this morning. Trees and overgrown ivy surround the monument, and it’s difficult to negotiate. We climb over felled trunks and limbs; the final step includes a big jump down over a ledge. Not much is known of the Braxton family, though some of their descendants still live in Richmond. The narrow mausoleum was probably erected in the mid-1920s. Five coffins rest within. At some point, probably in the 1950s, the steel door was ripped off, and the caskets removed and desecrated. Someone ran an illegal still inside the mausoleum, Shuck tells me. You can still see smoke stains on the ceiling.

The graveyard has a tendency to attract paranormal seekers. Shuck remembers finding odd string structures hung above and among the graves, telltale signs of hoodoo rituals. Vandals intruded for decades. Marijuana was grown on the property. It became, perversely, a destination for prostitution. Condom wrappers were a common find.

IV.

The volunteers are mighty busy. Within hours, an area at the center of the graveyard, radiating out from the Walker marker, looks as if it has always been well kept.

Photo: Michael JN Bowles

Memory Keepers

Harris and Shuck stand next to the marker of Rebecca Mitchell, the mother of John Mitchell, Jr. who ran for governor of Virginia in 1921.

“God called us to help fix it,” Marvin Harris tells me. “If the owners allow us to help fix it, it will get fixed.” The land is privately owned, and work came to a halt three years ago because of a dispute about using volunteers on private land. But that conflict was recently resolved. “For the average person with any type of heart,” Harris says, “I can’t see how they could not get involved.”

I speak with some of the volunteers. Bud Funk is a seventy-one-year-old trial attorney. He joined in after hearing Harris speak to a local group. “Marvin gets inside your heart,” Funk says. The first time Funk saw the site years ago it was “daunting.” Now he not only volunteers his back and limbs, but also does legal work in partnership with Enrichmond, a nonprofit that supports the effort. Other members of the Maggie L. Walker High School class of 1967 here this day include civil servants, an executive chef, and family members of those buried here. “My grandfather,” one man tells me. “I would come by here before, looking, and all I could see was trash.”

“No cemetery should fall into this type of landscape,” says John Baliles, a Richmond city councilman representing the 1st District. When I first spot him, he is doing battle with a long vine snaking its way about a large tombstone. “This will take a strong volunteer effort. But it is easier to preserve if you maintain it.”

There’s a stark contrast between the acreage cleared this morning and the work yet to be done. Just within a copse of trees a dozen or more gravestones poke up from the grass and undergrowth. Clearing the area will require heavier equipment and skill. Shuck and Harris have been discussing bringing in a herd of goats to help, and inviting a different corporate sponsor each month to pay for them.

V.

A virginia historian and business owner, Veronica Davis literally wrote the book about Richmond’s African American cemeteries, Here I Lay My Burdens Down, in 2003. Davis says the reclamation efforts began with a former National Park Service superintendent, Dwight Storke. Heartsick at these languishing sites of African American history, he spearheaded an attempt in the 1980s to have them cleared and restored. One part elbow grease, another part education, it started with a gathering of volunteers in celebration of Maggie Walker’s birthday. The initial volunteers removed fifteen truckloads of debris.

Over the decades, a series of Parks officials and local organizations arranged cleanups, and in the late nineties Davis herself created a group, Virginia Roots, to continue the efforts, but it has been slow going. Family members and volunteers move away or die off, and the cemeteries have gone through a number of private owners through the years. Without a system of perpetual care or funding, the work is difficult to maintain. Nor is the situation at Evergreen unique. Migration of families to the North during Jim Crow, scanty records, and a lack of public and private funds for upkeep have all led to the neglect of other historic African American cemeteries across the region.

“I thank God for this work every day,” Davis says. “We have to show

our ancestors respect for what they have done. We’re talking about

choices here, and we need to remember that one of the choices that

the dead made was to fight for our freedom. Now we have another

choice to make.”

Hidden-Cemetery.jpg

VI.

Midday: The Tony Award–winning actress L. Scott Caldwell arrives, dressed to work. Caldwell plays a formerly enslaved woman named Belinda on the PBS historical drama Mercy Street, which is shot on location in Richmond and nearby Petersburg. The actress is known for taking her research seriously, and visits not only the local museums and historical societies, but also places and sites central to African American history. She had heard about the project on the morning news. “It was a question of doing what I can to become a part of the community,” she says. “Where we are, there I am.” She was haunted by the story of Julia Hoggett, who was born into slavery. Hoggett’s gravestone is tucked under a mighty oak, and kudzu threatens to overgrow it. Caldwell had read about this marker during her research, and was keen to see it in person. It reads:

In Memory of my Mammy,

Julia Hoggett

1849–1930

She was born a slave and a slave she chose to remain.

Slave to duty, a slave to love.

Few people of any race or condition of life have lived so unselfishly,

which is the same as saying so nobly.

—LaMotte Blakely

Who was LaMotte Blakely? Was he a white child Julia Hoggett raised? “This spoke to me in a literal way,” Caldwell says. She is referring partly to her character, who in her freedom chooses to be the good and faithful servant of a well-to-do white family. But it’s more than that—there is a humanity here, a complexity, a dignity. She’s less interested in the big names and monuments, she tells me, than in those workers with unsung lives whose secrets are interred with their bones. “I’m more intrigued by the unknown than the known,” she says. “This is history.”

Cleanup efforts at Evergreen and East End cemeteries are ongoing. For updates and information on volunteering or donating through the Enrichmond Foundation, visit evergreencemeteryva.wordpress.com.