Sporting

Searching for Monster Trout on Georgia’s Soque River

On a small river outside of Atlanta, years of conservation and stewardship have paid off to create a fisherman’s paradise

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Guide Andy Brackett of Blackhawk Trophy Fly Fishing points out a trout on the far bank.

I could tell you

that it’s the river

I find so alluring.

In the headwaters, cornfields in the valleys nudge against sycamores and mountain laurel as the river, here little more than a creek, twists through banks clad in vine and wildflowers. Farther downstream, it gathers flow from limestone springs, and its rock-ribbed pools are cooled in the shade of soaring hemlock groves. The Soque River (pronounced so-quee) flows for about thirty miles contained in a single county—Habersham, merely four counties northeast of metro Atlanta—an intimacy that lends it a homey, winsome, tucked-just-out-of-sight appeal.

But I’d be lying if I said I’m here for the river—or the repasts spread on split-log farm tables or the end-of-day cocktails lit by a sun setting over wild, timbered ridgelines.

It’s the fish. I’m here for the sight of a two-foot-long rainbow trout leaping four times across a stream my dog could jump in a single bound, and the how-do-I-stop-it pull of big fish. I’m here for the trout that took my son, Jack, on a hell-for-leather sprint down the river.

I was working a nymph rig under a sycamore tree in a skinny section of the Soque when Jack hollered from upstream.

“Coming through, Dad! Reel up! Reel up!”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Brackett nets a Soque River rainbow.

I saw the line zing around the bend and then the bent top half of the fly rod and then Jack scrambling through the gravel-bar bushes, running in his waders. It was a big fish, unstoppable for the moment.

I took a big double step into the creek and crouched low so his rod and line could pass. He ran for another thirty yards, rod tip high, slipping on rocks and plunging through water to his thighs.

On the bank behind me, Mark Lovell laughed. His grandfather pieced this farm together, and his father expanded its boundaries in large part thanks to the moonshine that made him a legend in the area. He’s fished the Soque for most of his life. “But not much anymore,” he said. “I have more fun watching grown-ups like y’all fish and giggle like little kids.”

We watched downstream where Jack finally fought the rainbow trout to within distance of a long-handled landing net, and his guide stopped the fight with his second scoop. Lovell laughed again. “Now, that was something,” he said, chuckling. “Nobody’s walked on water like that since Jesus.”

There was a lot of giggling—and whooping and hollering and a fair bit of lost-fish cussing—during our five-day big-trout baptism in the Soque. The river flows through a pastoral farm-and-forest watershed, ultimately joining the Chattahoochee River, which provides drinking water to some five million people. In its headwaters in the rolling foothills north of tiny Batesville, the Soque is narrow enough to call a creek. Farther downstream, it widens to true small-river status, broad enough to handle a long backcast with a nine-foot fly rod. For decades, the river’s stature as a big-trout destination remained a bit of a local secret. But you can’t expect a place to stay secret for long when it coughs up six-pound rainbow trout and browns the size of your leg. Especially when the water is but a ninety-minute drive from downtown Atlanta.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

A healthy fish ready for release.

Lovell’s fly-fishing outpost, Headwaters on the Soque, is a perfect example of why folks fawn over the river. Over the last twenty years, Lovell says, his family has planted more than six thousand trees to help stymie stream erosion. In 2006, they brought in fifty-five dump truck loads of granite boulders and strategically placed the rocks along eroded banks and river bends. “In a lot of places,” he recalls, “the entire creek bottom was covered with dirt from banks sloughing off. Now you have to look hard to find any silt.” And those boulders provide fantastic trout habitat.

Stories of such stewardship are frequent refrains among Soque landowners. From top to bottom, the vast majority of the banks are privately owned, and many river frontage landowners have gone to great lengths to manage properties in ways that support large trout. At Blackhawk Trophy Fly Fishing, where spectacular groves of massive hemlock trees shade the river in Georgia’s summer heat, owners John and Abby Jackson have spent sleepless nights and tens of thousands of dollars to save the native trees from a non-native insect called the hemlock woolly adelgid. And at Fern Valley on the Soque, with two separate river stretches open for anglers, owners Marty and Glad Simmons shepherd rare fern species and a forest that could be used as a Tolkien movie set.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Guide George MacMillan on the river.

That sense of otherworldliness definitely finds expression at Brigadoon Lodge. The most luxurious property on the river, Brigadoon sits like a ring jewel inside a teardrop-shaped private inholding nearly surrounded by the Chattahoochee National Forest. The land was so wild when Rebekah Stewart, a former Wall Street investor, bought it in the early 1980s that she lived there for two years in a tent while clearing ground. She opened the place to anglers, she says, so she could pay for a land crew. Today Brigadoon includes a regal ten-room chalet called Cragganmore, adorned with massive game heads and Persian rugs, a smaller cabin, and a stunning mile of the Soque fed by seven springs and hemmed in by soaring cliffs.

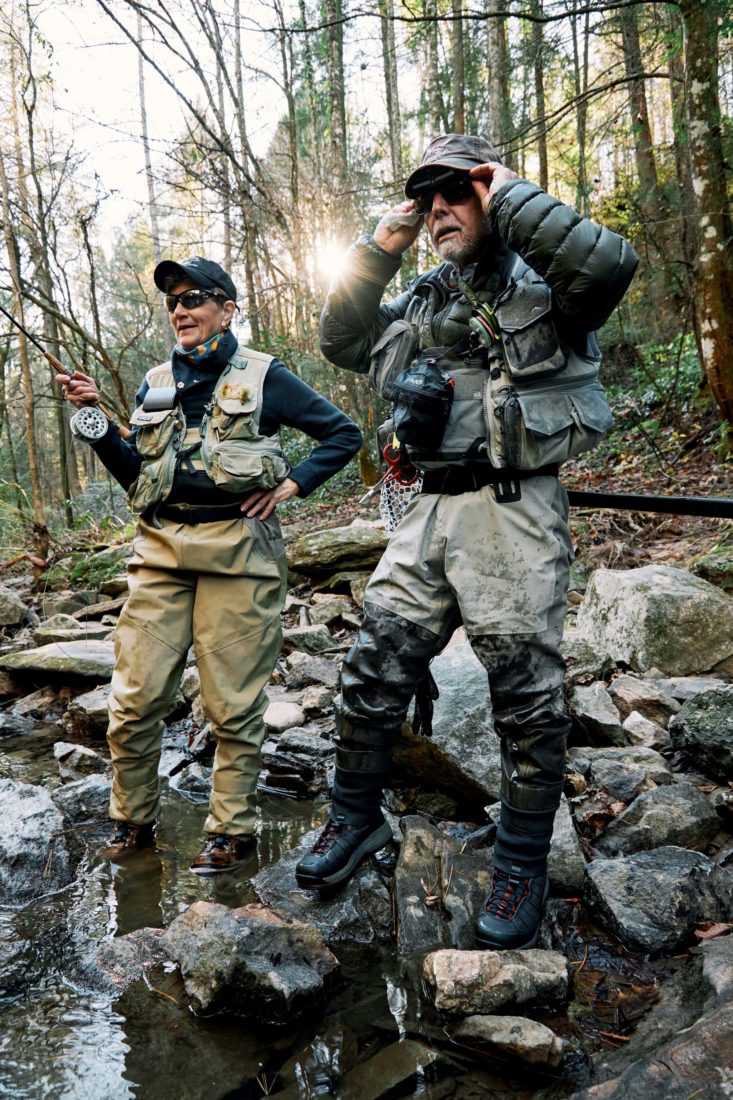

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Brackett and angler Candy Norton get ready to do battle.

All told, the efforts have created a pocket-size trophy-trout Shangri-la along the Soque, yet anglers should be eyes wide open about the experience. Private-water trout fishing has its detractors. These are stocked trout managed with supplemental feed. Catch-and-release requirements allow them to grow to nearly unnatural sizes. And there’s the impression that they are ridiculously easy to catch.

But the fact that such a long, nearly continuous stretch of the river is managed for these fish helps set it apart. Fishing pressure is limited. No fish are kept. “It’s unlike anything else out there, and certainly not in the South,” says John Burrell, whose High Adventure Company works with Headwaters on the Soque. The fishing isn’t always easy. These trout get targeted by very good anglers, know every fly in the box, and are on friendly terms with every log and sharp rock in the river. “I’ve seen the purest of the pure go crazy over this place,” Burrell says. “And this is for sure: If you want to learn how to fight a very large fish in very skinny water, which you might do in Alaska or British Columbia, you don’t want that to be your first rodeo.”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Testing the waters at the foot of Brigadoon Lodge.

You might instead want it to be a place where you don’t have to cross half the continent to find fish that will bend a rod to the cork, that will have you laughing out loud at the good fortune of catching trout that wouldn’t fit inside a mailbox. When you aren’t cussing them like a sailor.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

A blazing fire welcomes anglers at Brigadoon Lodge after a day on the river.

We fished through six

hours of stop-and-start drizzle, landing

rainbow trout after rainbow trout that often

broke the twenty-inch mark

Our plan was to start as far upstream as we could work a fly rod, and pick our way downstream, from outfitter to outfitter. Aptly named, Headwaters on the Soque contains the gathering of the left and right forks of the Soque into the mainstream of the river. It was the obvious choice for a starting block—and a memorable one. Built on the site of Lovell’s parents’ family home, the trim two-story lodge house overlooks a deep valley quilted with tawny cornfields, across which I could barely make out a meager sliver of the river hedged in by tall river birch and sycamores. Headwaters on the Soque covers about 650 acres, with just under four miles of trout water. It’s more than you could fish in a couple of long days.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

A beautiful rainbow comes to hand.

And they would be comfortable days, to say the least. Through its relationship with High Adventure Company, you can be as pampered at Headwaters as you wish to be—or left alone entirely. High Adventure can provide a private chef or a fully stocked kitchen. The staff will have bourbon waiting, or have a host there to mix the drinks. And you can have the spread to yourself, as Headwaters on the Soque can be rented as a private party destination.

The trip from coffee on the porch to a fly on the water takes less than fifteen minutes. Our guide, “Coach” George MacMillan, met us with a quiver of fly rods, but he was pleased to see we’d come armed with our own. We traded small talk and flies, reworked our leaders to his specifications, and got to work. I hooked a fish on my second cast, an eighteen-inch rainbow in the very pool that gathers the two main tributaries into the Soque proper, and the fish and the day took off in a rush.

MacMillan is a fixture on the Soque, with his graying locks that spill over a white sun visor. He draped a forearm over a battered and duct-taped landing net and told me about the family that he’s guided for twenty-three Memorial Day weekends in a row. “I’ve fished four generations of that family,” he said, a flash of pride showing through a gentle, humble demeanor. MacMillan spent nearly four decades as a physical education teacher and football coach—including thirty years in Habersham County alone. He retired from coaching three years ago. “But this is the best classroom,” he says, nodding toward the Soque. “People out here want to listen. I’ve never met anyone on this river that didn’t want to be here.”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

The end of a successful fight on the Soque.

He watched Jack stick one trout after another. Two hours into the morning, I was catching more fish than I deserved, but Jack was on fire. MacMillan grinned wryly. Jack landed a fish and stepped six feet upstream. MacMillan followed, deftly and unobtrusively, hanging back from the action so he wouldn’t crowd him. I halfway expected Coach to pull out a clipboard to diagram a few casts.

There you go, he murmured to himself, when Jack laid out a cast that unspooled under a river birch bough.

The fish were plentiful, but they weren’t stacked up. They had to be fished. We worked eddy lines and undercuts, fishing a double-drop rig armed with a brown stone-fly nymph and a lightning bug fly. MacMillan is an avid fly tier, a devotee of YouTube videos and whatever fishing techniques are on the cutting edge of the sport. “I’m studying all the time,” he said. “Right now, I’m figuring out European patterns, like the hard-bodied Perdigon nymphs with tungsten bead heads. We don’t get those big hatches like you see in Western streams. Eight bugs might be a caddis hatch, so we try a lot of things.”

We fished through six hours of stop-and-start drizzle, landing rainbow trout after rainbow trout that often broke the twenty-inch mark. When the sun finally worked its way through the clouds, the late light lit the ridges in a coat of burnished copper. In an era of large-scale plow-to-the-border farming, Headwaters on the Soque looks like a romanticized ideal of a mountain farm of the 1950s. Casting to a deep green slot beside a gravel bar seemed like casting into an Ed Cahill painting. I was in my own little world, until I glanced over at MacMillan.

He was in his. Jack was fighting another big fish, working it out from under a dark bank through a slot in the boulders. I watched MacMillan, his lips moving, his voice silent, speaking only to himself. That’s good. Yes, that’s good. He seemed as much a man in his element as I’d ever seen.

I hollered over: “You’ve never left coaching, have you?”

He grinned. “It never really leaves you,” he said quietly, as his eyes hovered on Jack. Then he broke into a bigger smile.

“But I did get rid of the parents.”

If any outfitter can claim status as patriarch of the river’s rising esteem among anglers, it’s Blackhawk. This year marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of the riverside complex. Set amid vegetable and flower gardens, a rustic 1860s farmhouse provides space for group lodging, a fly shop, a kitchen, and a kicked-back lounge. Blackhawk’s owners have deep roots in the area. John Jackson’s grandfather was the first doctor in the county. His wife, Abby, is widely known as a chef and gourmet foods purveyor whose pickles and sauces win awards.

Jack and I rolled in at midday, as the morning’s contingent of anglers were winding down with lunch and comparing notes. Across a massive outdoor table hewn from a six-thousand-pound slab of white oak, I chatted with one fisherman who’s been coming to Blackhawk almost since day one. “It’s been incredible to see it evolve,” he said. “There have always been good fish here, but it’s turned into something you can hardly imagine.”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Lunch at Blackhawk.

I was only halfway through my chili bowl when our guide, Andy Brackett, walked up. He wore waders that had seen more than a few river miles and a frayed ball cap with an angler’s magnifying lens clipped to the brim. A gray handlebar mustache anchored an impish face. Brackett’s eyes twitched from our lunch plates to our street shoes. He tapped his wader boot. I stifled a grin. He wasn’t here to share a sandwich. This man was wired to fish.

“Lunch is over, Jack,” I said. “Grab your waders.”

Ten minutes later we were on the water, and our half-day trout rodeo commenced. The Soque at Blackhawk carries five times the flow of the upper river sections, with plenty of room for forty feet of fly line when you need it. If fighting a significant fish in a Headwaters beat is a mixed martial arts cage match, dealing with a six-pound Blackhawk rainbow is an old-school boxing bout, with plenty of time and room for feints and parries to grind down your opponent.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

A rainbow’s shimmering flanks.

Brackett spent twenty years in the U.S. Navy, then guided flats anglers in the Florida Keys for eleven years, and has logged fifteen seasons on the Soque. “At this point in my life,” he said, “if it’s not fun, I don’t want any part of it.” It was sometimes difficult to tell who was having the most fun.

While I cast, Brackett was bent over at the bottom of each run or pool, knees flexed, hands on his thighs. At times he was literally bouncing. MacMillan may be the eternal head coach, but Brackett is the offensive line coordinator, scrambling up and down on the sidelines, totally invested in every play. With every good fish, he stuck his head halfway into the net, laughing and chuckling.

Look at you, ya big slabbie!

What a chunk!

Oh, yes, what a fine girl you are!

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Brigadoon guide Mark Dixon lands a trout.

And there were fine fish aplenty. Like Lovell on the Headwaters stretch, the Jacksons tend to their length of river with paternal care. Ten years ago, Brackett told me, a serious drought hit the region. Hot weather for three straight months, and the Jacksons knew the bigger fish would school into the deeper pools, and many might not survive.

Most operations on the Soque are closed to fishing in the hottest months, when fish struggle in the warmer waters. But this was an emergency that required additional triage. The Jacksons rented large, hospital-sized oxygen bottles and ran multiple diffusers into the pools. Every three days, Brackett waded in to scrub the diffuser heads. “We kept at it for the better part of two weeks,” he says. “You can buy a bunch of fourteen- and fifteen-inch fish and throw them in the water and call it fishing. But that’s not the program here. Some of our trout are eight years old. That was a heroic effort, and we did it because we want to take care of these fish.”

We had challenges of our own. In the brisk air of the next morning, we went fishless for an hour as the water temperatures struggled to rise. Jack and I separated to double our chances, and as he disappeared upriver, Brackett riffled through four fly changes and switched my rod twice, to no avail. We were alone on the river, and he made no apologies for the early start. “These fish might not wake up for a bit,” he avowed, “but we’re gonna stick the first one that opens its mouth.”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Searching for the perfect fly.

That card fell to Jack. He emerged from the mountain laurel thicket that curtained the riverbank, his forehead glistening

with sweat.

“Tell me a freaking story, Jack!” Brackett implored.

Jack shook his head.

“Big,” he said, grinning sheepishly. “Jump. Jump-jump-jump-jump-jump. Big. Gone.”

Brackett slapped his waders. “See? People come here from all over the world and they have their asses handed to them! What a blast!” His love for the river and enthusiasm for these fish rang across the water.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

The dining room in Brigadoon’s main lodge.

Not that every moment of our five days on the Soque was a hoot and holler. The river’s mercurial personality demands a different fishing approach and skill set as you move from stretch to stretch, and getting tuned to what the fish wanted sometimes required patience and a deep fly-box bench. There were times when I had to nearly will myself to dial back on such a fish-centric focus and soak in a bit of the world around me.

And there were times when the river made it impossible to do anything but.

At one point Brackett and I were knee-deep in a long left-hand river bend. I lobbed a double-nymph rig into a dark groove of the Soque, when suddenly sunlight blasted from downstream. The uppermost crescent of the low sun had cleared the mossy trunk of a fallen hemlock, and the beam shattered into a thousand shafts of light. Passing through the rhododendrons and hemlocks, each shaft twinkled on the water. The bubble lines and eddies shimmered like broken glass.

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

An angler comes tight with a fish at Headwaters on the Soque lodge.

I turned from the fly and line in mid-float to watch the bottom half of the sun clear the downed tree.

“Could you turn down the beauty just a bit?” I asked Brackett. “It’s making it hard to fish.”

This time, there was no boisterous laugh, no cackle of delight. Just a murmur of assent.

“Sometimes it feels like you come around a bend in the river

and God decides to suddenly turn on all the lights,” Brackett said. “Like he wants you to know: ‘I’m still here, boys. Enjoy.’”

Photo: Peter Frank Edwards

Gathering round the fire at Headwaters.