Travel

The Hidden Caribbean: Paradise Found

Five islands where you can still escape the crowds

Photo: Jen Judge

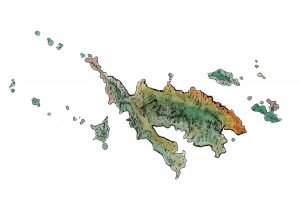

Culebra

Tropical Time Warp

It would not be unreasonable, or particularly original for that matter, to think of Culebra as a sort of twelve-square-mile blank slate—a tropical destination stripped down to its essentials: baking sun, iridescent clear shallows in ravishing shades of turquoise and cerulean, silky white sand…and not a whole lot else. Like its better-known Puerto Rican sister, Vieques, Culebr a was a bit of a late bloomer. From the onset of World War II until 1975, the U.S. Navy used it as a practice bombing range and weapons testing ground, thereby unwittingly (and ironically) keeping developers at bay and the beaches and coral reefs relatively pristine. Even now, the island remains a time-warp frontier of often rutted roads, rattletrap rental Jeeps, overzealous roosters, unpalatial guesthouses and villas, and uncrowded shoreline. Seabirds far outnumber humans. Traffic lights don’t exist. Travelers don’t just figuratively downshift here; they turn off the ignition and throw away the keys. If you just happen to “forget” your return flight home, you won’t be the first.

a was a bit of a late bloomer. From the onset of World War II until 1975, the U.S. Navy used it as a practice bombing range and weapons testing ground, thereby unwittingly (and ironically) keeping developers at bay and the beaches and coral reefs relatively pristine. Even now, the island remains a time-warp frontier of often rutted roads, rattletrap rental Jeeps, overzealous roosters, unpalatial guesthouses and villas, and uncrowded shoreline. Seabirds far outnumber humans. Traffic lights don’t exist. Travelers don’t just figuratively downshift here; they turn off the ignition and throw away the keys. If you just happen to “forget” your return flight home, you won’t be the first.

Photo: Jen Judge

A military relic.

1 of 4

Photo: Jen Judge

A curious Chihuahua.

2 of 4

Photo: Jen Judge

Ready to cast.

3 of 4

Photo: Jen Judge

A passing schooner.

4 of 4

In fact, a visitor’s toughest assignment on Culebra might be deciding on a favorite beach. Try a shotgun approach: Playa Flamenco is a mile-long sugar crescent regarded as one of the Caribbean’s most beautiful shorelines; a pair of graffiti-adorned tanks half buried in the sand hark back to the military’s island occupation. Both Zoni and Carlos Rosario require more effort to reach but reward snorkelers with the company of sea turtles and reef fish just offshore. Board a water taxi or paddle a rented kayak to Culebrita, an uninhabited cay with solitudinous stretches of sand and a crumbling lighthouse, or hilly Cayo Luis Peña, part of the Culebra National Wildlife Refuge, designated by Teddy Roosevelt in 1909. Head for Playa Melones, just west of Dewey, the island’s lackadaisical attempt at a town, for sunsets. The island is a lotus-eaters’ buffet.

If you insist on a challenge, try hooking a bonefish on Culebra’s isolated flats. Bones are scarcer here than in renowned fishing grounds like the Bahamas, but they make up for it in size: typically five to six pounds, says guide Chris Goldmark. And in spring “a lot in the nine-to-ten-pound range.”—Mike Grudowski

Island Notes

Chasing Bones

For a shot at a big Culebra bonefish, you can’t do better than a trip with Chris Goldmark, who splits his time between Culebra and New Jersey

and has guided here for twenty-four years. Permit and tarpon are also possibilities, as well as an offshore charter.—culebraflyfishing.com

Culebra Cuisine

No one comes here for fine dining (or speedy service), but there’s good eats if you know where to look: El Batey for slow-cooked lechón, El Panino food truck for addictive grilled sandwiches, Mamacita’s for cocktails and local color, and Dinghy Dock for seafood, Puerto Rican specialties like pastelón (a version of lasagna with plantains), and a chance to feed table scraps to the congregating tarpon.

Bayside Bungalows

Club Seabourne is a favorite resort of sanjuaneros from the “big island.” It has a dozen villas overlooking Fulladoza Bay, a pool, and a private dock.—clubseabourne.com

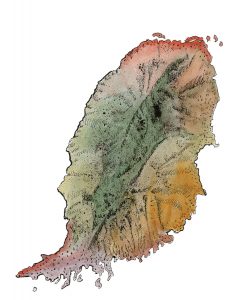

Domenica

The Island Primeval

Photo: Jen Judge

Green Space

A cabana at the Pagua Bay House.

“I had not believed that anything could be so green,” wrote the itinerant English author Alec Waugh upon visiting Dominica in the late 1940s,  when the island nation was still a British colony. “It is all a tangle of bamboo and ferns and vine, of palms and mahogany and mango, of cedar and bay and breadfruit trees. It is green, all green.” Odds are the novelist would still recognize the place if he deplaned there now: Two-thirds of the island is still cloaked in rain forest. Dominica—it’s pronounced dom-uh-neek-a—remains an unspoiled outlier, populated by rare and rainbow-plumed Sisserou parrots, huge and centuries-old gommier trees and tiny orchids, more than 350 rivers and streams, dozens of waterfalls, peaks as high as 4,700 feet, and 300 miles of hiking trails. Leatherback turtles nest on black sand beaches, sperm whales linger year-round just offshore, and the island’s 70,000-some inhabitants live amid one of the highest concentrations of potentially active volcanoes on earth. The names of some of the island’s more exotic locales sound as if they were lifted straight out of Treasure Island or Peter Pan: Boiling Lake (a flooded, volcanic fumarole that does very nearly boil). Emerald Pool. Indian River. The Valley of Desolation. Stinking Hole, which would make for a fitting name for a bar frequented by undergraduates but here indicates a steaming lava tube redolent of bat guano.

when the island nation was still a British colony. “It is all a tangle of bamboo and ferns and vine, of palms and mahogany and mango, of cedar and bay and breadfruit trees. It is green, all green.” Odds are the novelist would still recognize the place if he deplaned there now: Two-thirds of the island is still cloaked in rain forest. Dominica—it’s pronounced dom-uh-neek-a—remains an unspoiled outlier, populated by rare and rainbow-plumed Sisserou parrots, huge and centuries-old gommier trees and tiny orchids, more than 350 rivers and streams, dozens of waterfalls, peaks as high as 4,700 feet, and 300 miles of hiking trails. Leatherback turtles nest on black sand beaches, sperm whales linger year-round just offshore, and the island’s 70,000-some inhabitants live amid one of the highest concentrations of potentially active volcanoes on earth. The names of some of the island’s more exotic locales sound as if they were lifted straight out of Treasure Island or Peter Pan: Boiling Lake (a flooded, volcanic fumarole that does very nearly boil). Emerald Pool. Indian River. The Valley of Desolation. Stinking Hole, which would make for a fitting name for a bar frequented by undergraduates but here indicates a steaming lava tube redolent of bat guano.

Photo: Jen Judge

Fish and dumplings at Portsmouth food stall.

Which is to say, Dominica is the West Indies served up raw and real: no mega resorts, no long crescents of groomed white sand, no casinos, and no nonstop jets from the States. (American visitors usually catch a connecting turboprop in San Juan, St. Maarten, or Antigua.) It draws explorers who perk up at the thought of steep hikes through the otherworldly rain forest of Morne Trois Pitons National Park, eco-lodges boasting solar-heated water, unassuming menus centered around organic produce and fish that was still swimming this morning, ramshackle roadside rum shops, snorkeling among geothermally warmed bubbles at Champagne Reef, simmering in natural hot springs, and cowabunga plunges into Edenic waterfall pools. Still green…all green.—Mike Grudowski

Island Notes

Treehouse Chic

On the northwest coast, Secret Bay’s plush villas and bungalows—like treehouses straight out of Architectural Digest—raise the bar for high-end lodging on Dominica. The staff can stock your well-appointed kitchen with food and sommelier-curated wines. Or leave the cooking to a personal chef for hire.—secretbay.dm

Grand Canyoning

Don’t come all the way here just to gawk at scenery. Extreme Dominica’s guides will have you rappelling down waterfall chutes and leaping off boulders into crystalline pools.—extremedominica.com

River of Rum

During a guided rowboat ride up the jungly Indian River near Portsmouth, flanked by the gnarled roots of “bwa mang” trees, stop in to the Bush Bar for homemade rum infused with local fruits and herbs and a plate of smoked fish.—cobratours.dm

Grenada

Isle of Plenty

Photo: Michael Turek

Catching a ride in St. George’s inner harbor.

You could narrow down which island to visit based on beaches, sailing, historical relics, reefs, food, or rum. Or you can simply opt for a  destination unlikely to disappoint any West Indies connoisseur. “The first time I came to Grenada, in 1996, I was blown away by the place,” says Jerry Rappaport, a native New Yorker and Grammy-winning record producer who has lived on the island for fifteen years and helps run La Sagesse, a small hotel on the south coast, with his wife. “It still has what a lot of the Caribbean has lost.” Long known as the Spice Island for its aromatic bounty of nutmeg, cloves, vanilla, cinnamon, and the like, Grenada is blessed with a natural setting that lacks nothing: There are glorious palm-shaded strands, such as the nearly two-mile-long Grand Anse, a sugar-sand beauty just south of the capital, St. George’s. A Jurassic interior with idyllic waterfalls, lakes filling spent volcanic craters, and dense stands of mountain palm, strangler-fig vines, gargantuan ferns, fifty-foot-tall bamboo, and bromeliads latched onto tree trunks. A diver’s banquet of reef walls, coral gardens, shipwrecks, sea horses and turtles, and an eerie underwater sculpture park in Molinere Bay. Inviting resorts that range from colonial manor house to Côte d’Azur yacht-club chic.

destination unlikely to disappoint any West Indies connoisseur. “The first time I came to Grenada, in 1996, I was blown away by the place,” says Jerry Rappaport, a native New Yorker and Grammy-winning record producer who has lived on the island for fifteen years and helps run La Sagesse, a small hotel on the south coast, with his wife. “It still has what a lot of the Caribbean has lost.” Long known as the Spice Island for its aromatic bounty of nutmeg, cloves, vanilla, cinnamon, and the like, Grenada is blessed with a natural setting that lacks nothing: There are glorious palm-shaded strands, such as the nearly two-mile-long Grand Anse, a sugar-sand beauty just south of the capital, St. George’s. A Jurassic interior with idyllic waterfalls, lakes filling spent volcanic craters, and dense stands of mountain palm, strangler-fig vines, gargantuan ferns, fifty-foot-tall bamboo, and bromeliads latched onto tree trunks. A diver’s banquet of reef walls, coral gardens, shipwrecks, sea horses and turtles, and an eerie underwater sculpture park in Molinere Bay. Inviting resorts that range from colonial manor house to Côte d’Azur yacht-club chic.

Photo: Michael Turek

Grand Anse.

1 of 5

Photo: Michael Turek

Danny Donelan of Port Louis Marina.

2 of 5

Photo: Michael Turek

Spice Island Beach Resort.

3 of 5

Photo: Michael Turek

Captain Walter Olivierre on the sailboat Savvy.

4 of 5

Photo: Michael Turek

Strolling in St. George’s.

5 of 5

Much of Grenada’s magnetism lies not in touristy trappings but in its throwback charm. Drivers need to keep an eye out for strolling Rastafarians, bush dogs, rolling coconuts, tethered donkeys, and armadillos. Villagers sell grilled corn by the roadside. Fishermen still haul nets onto the beach. Island elders recall when the ice-delivery man would sound a blast on a conch shell to signal his arrival. At market stalls, you come across nutmeg syrup, nutmeg pancakes, nutmeg ice cubes, nutmeg soap, Nut-Med pain relief spray. Minibuses have cryptic decals plastered on their windshields: JAH GUIDE, TALK SPREAD, D FLY. It’s true that expatriate investors, such as the English oil-and-shipping magnate Peter de Savary, have gazillion-dollar plans to boost the number of exclusive resorts. And some islanders fret about what’s to become of their enclave (one sign of the apocalypse: Disney cruise liners have begun making stops). But the island hasn’t been overrun, and it’s hard to imagine that travelers won’t still be falling hard for Grenada a hundred years from now. And a hundred years after that.—Mike Grudowski

Island Notes

Rooms with a View

Locally owned Spice Island Beach Resort has airy suites with whirlpool tubs along Grand Anse (spicebeachresort.com). Farther north, Mango Bay is a low-key oceanfront refuge with kitchen-equipped cottages and a zigzaggy staircase leading down to a private beach (mangobaygrenada.com). La Sagesse, a twelve-room manor house once owned by a cousin of Queen Elizabeth’s, sits on a cove about thirty minutes from St. George’s (lasagesse.com).

Eco-Chocolate

It doesn’t get any greener than dark chocolate from the Grenada Chocolate Company, made with organic cacao beans in a solar-powered factory and delivered to nearby islands via Hobie Cat.—grenadachocolate.com

Pedal Power

Mocha Spoke—housed in two bright-yellow shipping containers—pairs bike rentals and tours with a menu of espresso drinks and breakfast and lunch offerings; try a Caribbean Mocha, with coconut milk and extra chocolate.—mochaspoke.com

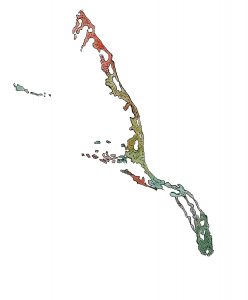

Long Island

Bonefish Bonanza

Photo: Tosh Brown

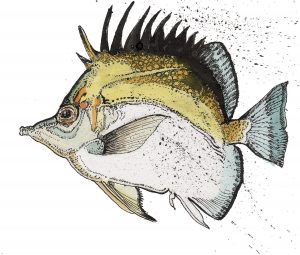

Silver Bullet

A nice bonefish in Hand.

Long Island may be only 160 air miles southeast of Nassau, but it’s an entirely different slice of the Bahamas. The only sense of glitzy tourism  you get here happens when you stand on the beach at night and watch cruise ships glimmer on the horizon.

you get here happens when you stand on the beach at night and watch cruise ships glimmer on the horizon.

With fewer than five thousand residents, this quiet “out island” stretches eighty miles from Columbus Monument and Cape Santa Maria in the north (Columbus made one of his first landings in the New World here) to Gordon’s Settlement in the south, yet it is at most only four miles wide. Terrain is often rocky, and even hilly—anomalies for most Bahamian islands. Its eastern shore is buffeted by swells from the open Atlantic, while the western coast—typically the lee shore—features an elaborate labyrinth of calm bays, shallow flats, and mangrove cays that create a massive bonefish Shangri-la.

Granted, almost every one of the seven hundred islands in the Bahamas offers some type of flats fishing appeal, but what sets Long Island apart are the abundant do-it-yourself opportunities. Pick up a rental car and you can easily hop from flat to flat on the skinny island.

There are indeed excellent fishing guides—the likes of Loxley Cartwright, Markk Cartwright, and Docky Smith—and resorts such as Stella Maris offer guided fishing packages. But if you want to tackle the supreme fly-fishing challenge of stalking, spotting, casting to, and landing a silver bullet on your own, this is one of the best places in the world to do so. It’s usually best to concentrate on the northern and central flats, which are typically firm and easy to wade (with boots). Anglers here are apt to encounter large schools of smaller fish, as well as cruising pairs and singles. The solitary swimmers can press double digits in weight. And given the relatively light fishing pressure, a well-presented staple fly pattern, like a tan #6 “Gotcha,” is often like ringing the dinner bell.

Do take time to explore the island as well, and soak in some authentic Bahamian culture. A day trip to Dean’s Blue Hole—a geologic wonder and popular spot for cliff jumping, snorkeling, and beach lounging—is well worth the effort. Just keep your rod close. A few bonefish have been known to swim the periphery there, too.—Kirk Deeter

Island Notes

DIY Bonefish

Nevin “Pinky” Knowles created the Long Island Bonefishing Lodge specifically to cater to independent-minded anglers. The staff takes you by

boat to a flat (with lunch and water) for “assisted” walk- and-wade fishing—a guide remains on the flat in case you need him, but you’re free to explore. At day’s end, it’s a quick run back to the lodge, where conch fritters and cold Kalik beer await.—longislandbonefishinglodge.com

Into the Blue

Stella Maris Resort Club’s accommodations range from bungalows to water-front homes with private pools, and the staff can arrange blue-water charters for tuna, wahoo, and more.—stellamarisresort.com

Beach Retreat

Located on the island’s northern tip, Cape Santa Maria Beach Resort sits on four miles of one of the prettiest stretches of white sand anywhere.—capesantamaria.com

Petit St. Vincent

Secluded Sanctuary

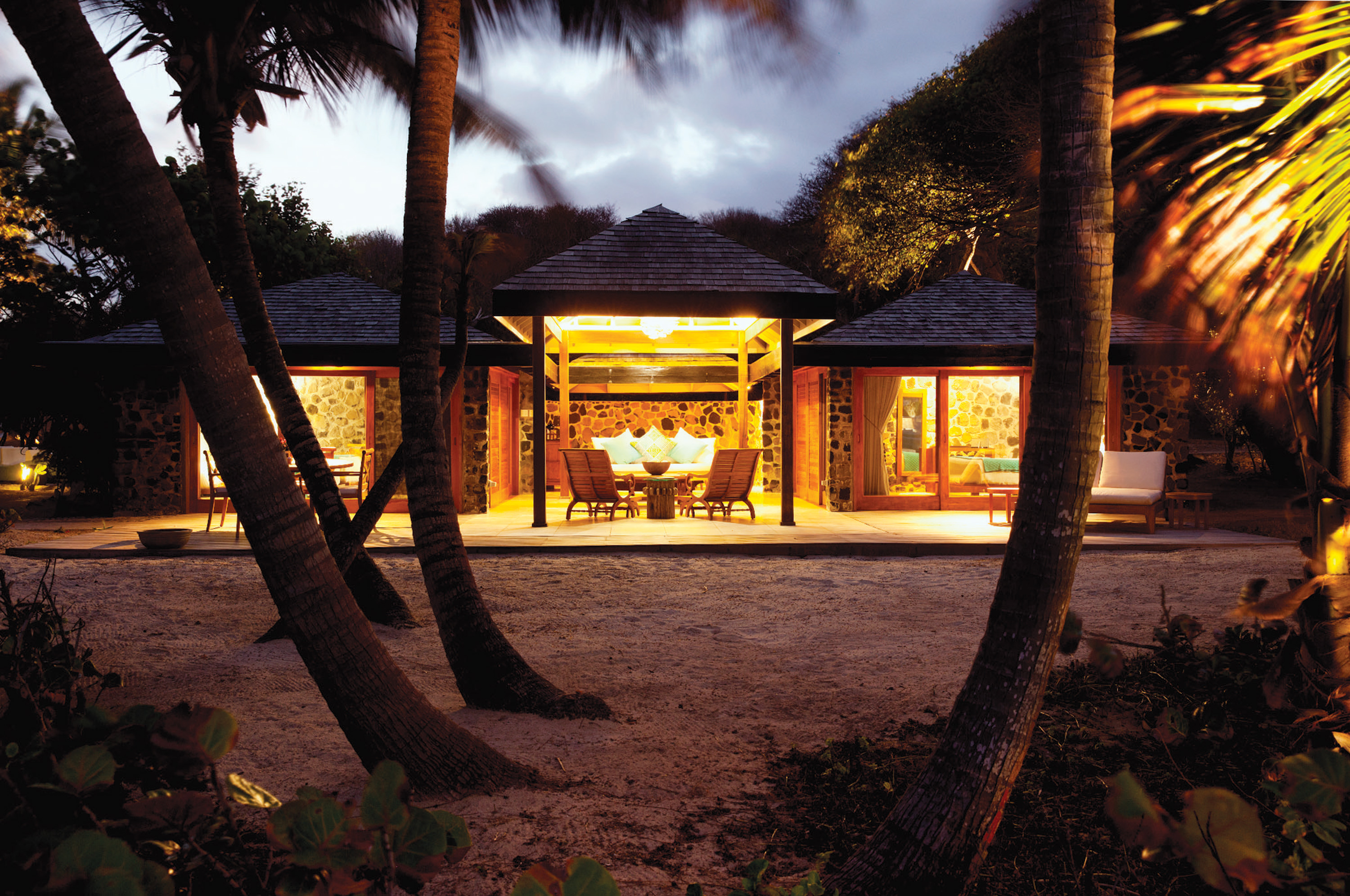

Photo: Courtesy Petit St. Vincent

A quiet evening on Petit St. Vincent.

It started with pure serendipity. In 1962, a New England native named Haze Richardson, fresh out of the air force, launched a crewed charter  business with his friend and fellow flyboy Doug Terman aboard their seventy-seven-foot schooner, Jacinta. Their first client, an Ohio industrialist named H. W. Nichols, mentioned that he’d like to buy an island somewhere; could the two sailors help? One thing led to another. By 1966, the three found themselves the owners of a scraggly and uninhabited 115-acre outpost in the Grenadines that had long been little more than goat pasture. After laboring at everything from laying electrical cable to planting trees to helping build twenty-two purpleheart-and-volcanic-stone cottages, Richardson became the manager, and eventually owner, of Petit St. Vincent resort from its 1968 opening until his death forty years later. The remote island had no airstrip; guests arrived by boat (usually greeted at the dock by a couple of Richardson’s yellow Labs). Each cottage was blissfully secluded, luxuriously appointed but without phones, televisions, clocks, or even locks on the doors. There was nothing quite like it.

business with his friend and fellow flyboy Doug Terman aboard their seventy-seven-foot schooner, Jacinta. Their first client, an Ohio industrialist named H. W. Nichols, mentioned that he’d like to buy an island somewhere; could the two sailors help? One thing led to another. By 1966, the three found themselves the owners of a scraggly and uninhabited 115-acre outpost in the Grenadines that had long been little more than goat pasture. After laboring at everything from laying electrical cable to planting trees to helping build twenty-two purpleheart-and-volcanic-stone cottages, Richardson became the manager, and eventually owner, of Petit St. Vincent resort from its 1968 opening until his death forty years later. The remote island had no airstrip; guests arrived by boat (usually greeted at the dock by a couple of Richardson’s yellow Labs). Each cottage was blissfully secluded, luxuriously appointed but without phones, televisions, clocks, or even locks on the doors. There was nothing quite like it.

There still isn’t. The cottages, beachside or hillside, remain elegantly spacious and understated (air-conditioning is now an option, as is Wi-Fi, if you must, but only at a small central terrace). Guests still voice their preferences with signal flags at the path leading to their hideaway: A yellow flag means “we need something”—afternoon tea or cocktails, a ride to dinner on one of the golf-cart-looking Mini Mokes, a sunset sail; red means we’re doing just fine, thank you. The prime attractions remain the same ones that originally lured loyal (and well-heeled) vacationers: warm aqua shallows, nearly two miles of white sand, a wreath of coral encircling the island and luring snorkelers, a sheikh-worthy staff-to-guest ratio, and splendid isolation. (Before the Internet and cell phones, Richardson himself once remarked that he kept abreast of world events only by reading copies of Time magazine that guests left behind.)

Photo: Courtesy Petit St. Vincent

State-of-the-art communication.

After all these years, it’s still not particularly easy to get to. Guests arrive by private launch, after a short twin-engine flight to nearby Union Island and a long flight to Barbados before that. But it’s even harder to leave.—Mike Grudowski

Island Notes

Relaxation Station

To help you get down to speed with your surroundings, a team of Balinese massage therapists mans a four-room haven tucked in among the trees, ready to administer deep-tissue, warm-stone, and other indulgent treatments.

Day-Tripping

Charter a day sail on the forty-nine-foot sloop Beauty to nearby Grenadine islands such as Mustique, Canouan, and the Tobago Cays, an uninhabited marine reserve ideal for hours of snorkeling or world-class beach slumming.

Dining Alfresco

In addition to meals in your cottage or at one of the two restaurants, PSV’s staff can also arrange picnic lunches or a private dinner anywhere on the island: in a gazebo at the end of the Windward Dock, on the beach, or on a tiny sandbar called Mopion, a short boat ride away.