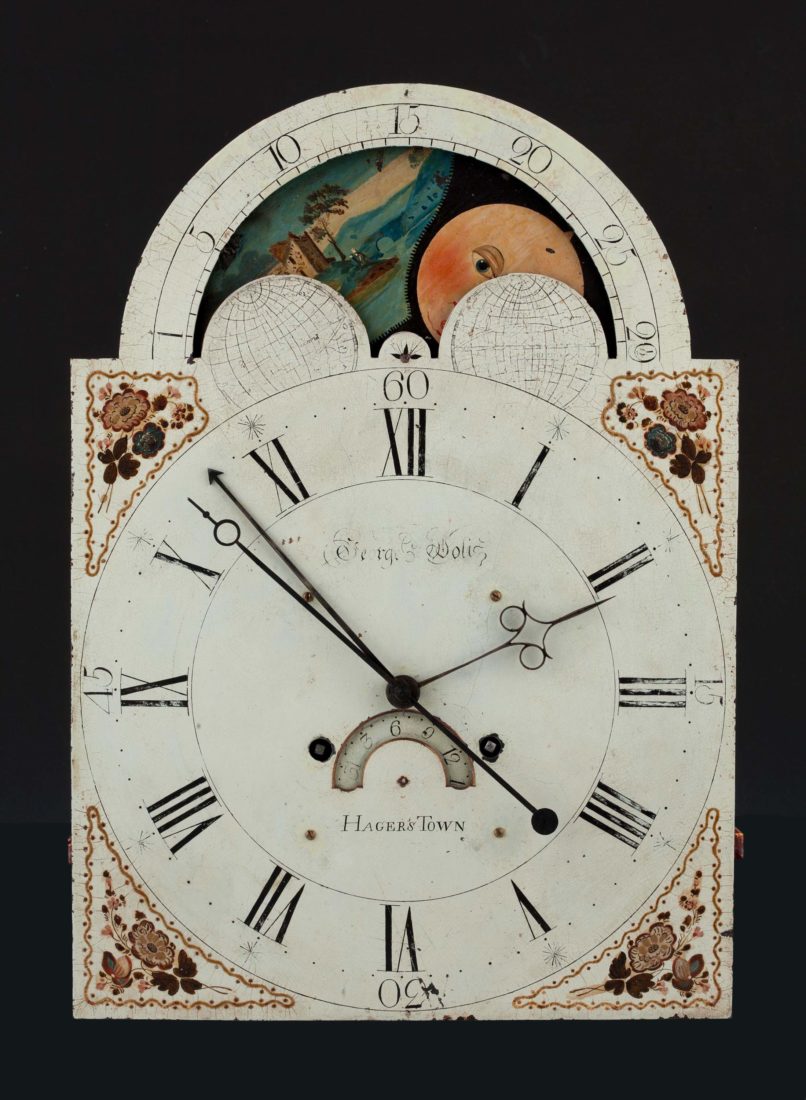

A tall case clock with movements made by George Woltz in Hagerstown, Maryland, between 1795 and 1805. The unknown cabinetmaker who designed the case drew from British-inspired trends in nearby Baltimore.

Photo: Courtesy of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg

Hagerstown clockmaker George Woltz also crafted this tall case clock around 1800. A local cabinetmaker called on traditional Pennsylvania designs of the time but used local sumac rather than the fine-grained woods most often employed by urban cabinetmakers.

Photo: Courtesy of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg

Luman Watson, a clockmaker in Cincinnati, Ohio, fashioned the economical wooden movements between 1819 and 1829 and sold them to Lexington, Kentucky, cabinetmaker Elijah Warner, who crafted the cherry, tulip poplar, and mahogany case. The duo brought this streamlined style, already popular on the East Coast, to the inland South.

Photo: Courtesy of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg

A close-up on the Watson-Warner clock.

Photo: Courtesy of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg

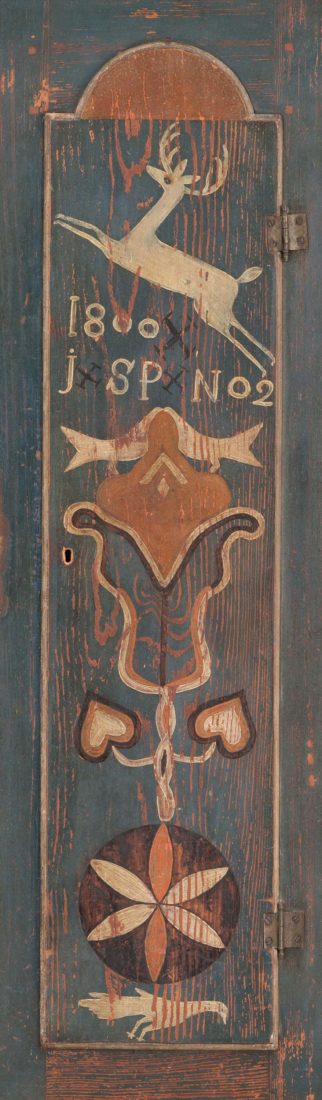

Johannes Spitler, a painter who descended from a Swiss Mennonite family that moved from Pennsylvania to Shenandoah County, Virginia, decorated this tall case clock in 1800. Spitler covered the yellow pine case with hearts, rosettes, and animals including a stag and a bird common in German-American art from Pennsylvania, Virginia, and North Carolina.

Photo: Courtesy of the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg