Music is a way of life that has pulsated at the center of New Orleans’ unique culture since its French origins in the eighteenth century. The city’s most significant musical contribution, jazz, which appeared just prior to 1900, was both an evolution of celebratory traditions and the voice of an oppressed African American population seeking social justice and equality. Too hot and danceable to be contained, jazz’s driving rhythms and collective improvisation reached all incomes, races, and places — dances, picnics, sports events, boat rides, and weekend excursions along Lake Pontchartrain. Black social and benevolent organizations spread the democracy-based music through community parades and funerals in which marching brass bands were accompanied by a large crowd of anonymous dancers of all ages called the second line.

While, throughout the twenties, King Oliver, Jelly Roll Morton, and Louis Armstrong helped launch New Orleans music from northern cities, jazz continued to thrive locally in neighborhoods and musical families. Its sound and spirit influenced later forms of music of which the Crescent City produced leading figures, such as gospel great Mahalia Jackson and R&B legend Fats Domino. The heritage of New Orleans music continues today in several different styles, with internationally successful artists such as Aaron Neville, Harry Connick, Jr., Wynton and Branford Marsalis, Dr. John, and Lil Wayne. But today’s famous musicians represent only a small fraction of New Orleans’ rich wellspring of talented performers. Dozens of lesser known individuals have spent much of their lives and careers in their city, dividing their time between family, day jobs — and performing. These musicians have had a wide range of adventures and experiences, and some have survived hardship; yet, in their later years they continue to perform and inspire younger generations through the traditional jazz roots of New Orleans’ musical heritage.

This greatest musical culture in American history was severely affected when Hurricane Katrina nearly destroyed New Orleans. Many musicians lost their homes and possessions, hundreds were scattered throughout the country, and scores have not returned. Among the musicians who have returned and resumed their careers are a group of veteran performers whose will and spirit are a testimony to the resilient nature of New Orleans music.

Continuing the tradition of using music as a means of survival and triumph over adversity, they perform whenever they can in clubs, at festivals, for weddings, parties, and brunches. The unique jazz funeral tradition of slow sad pieces and joyous up-tempo music with dancing has shown them how to mourn, let go, and move optimistically toward the future. Music has helped them cope with tragedy and loss, to comfort and find comfort in others, and to bring back a degree of normalcy. These elder statesmen share their musical gifts with a strength and determination that defies skeptics and assures that the music of New Orleans will live on forever.

Donn Young

Lionel Ferbos

Born July 17, 1911

The oldest active musician in New Orleans, Lionel Ferbos was born and spent all of his ninety-six years in the downtown Creole section of the city. He was first inspired to play music when he heard trumpeters in an all-girls band; then, at fifteen, he began private lessons. He started playing New Orleans-style jazz and popular dance music at house parties and restaurants, then he toured throughout the South on the famous Theater Owners’ Booking Association circuit.

Back in New Orleans by the early 1930s, he played in the Works Progress Administration Band and with local big bands. To raise his family, Ferbos settled in a longtime trade as a sheet metal worker, but except for a brief layoff due to medical problems, he continued to play music all of his life.

“Some guys wouldn’t hire me ’cause they said I read too much!”

In the early 1970s his sweet trumpet tone and excellent reading ability led to his long-standing membership in the New Orleans Ragtime Orchestra, with which he made several recordings and appeared in feature films such as Pretty Baby. Beginning in the late 1970s he was the original trumpeter and a featured vocalist in the hit musical One Mo’ Time.

Ferbos has remained self-conscious about his playing. He writes out his solos, and while he knows dozens of songs by memory, on jobs he reads many of the songs from sheet music. He takes a humorous view of his approach and trademark music stand: “Some guys wouldn’t hire me ’cause they said I read too much! I look at it this way: Al Hirt had his beard; Kermit Ruffins has his hat; I have my stand!”

Ferbos’ home flooded in Katrina and was severely damaged; most of his possessions were lost. In the meantime, he also lost his son. Now Ferbos lives with his ailing wife of seventy-three years and their daughter-in-law in an apartment, and doesn’t know if he will ever return to his home. Yet he can still be found, one night a week, playing at the Palm Court Jazz Café, where he has played for the past fifteen years.

Donn Young

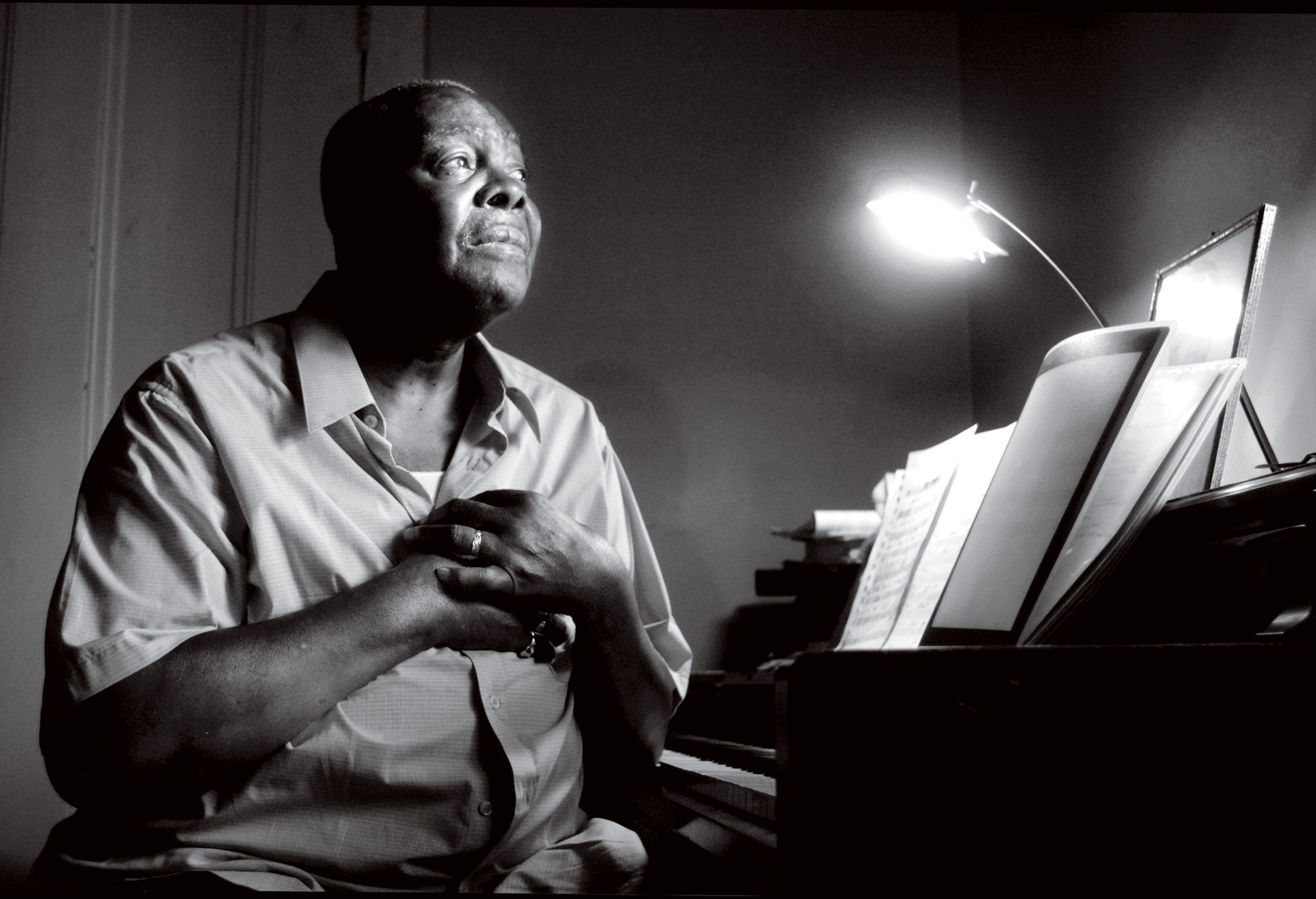

Lawrence Cotton

Born February 2, 1927

Lawrence Cotton was born in uptown New Orleans, near the Mississippi River, where he has lived all his life. Inspired by his father, an amateur pianist, he was self-taught until he began taking lessons after a stint in the Air Force. His first professional job was at a local club with bassist Lloyd Lambert’s rhythm and blues band.

The group soon took to the road and backed up a number of R&B stars, including Joe Turner, T-Bone Walker, and Guitar Slim. Constant travel could be grueling, and though he says everyone was like a family, Cotton left in 1958, after four years. Legendary Guitar Slim had warned him about the dangers of leading a fast life on the road: “Cotton, you’re going to outlive me ‘cause I’m living two or three days to your one.” Slim died in 1959 at age thirty-two.

Back in New Orleans, Cotton played the next few years with local R&B groups, including the band of legendary performer-producer Dave Bartholomew. During the 1970s he began playing traditional jazz in Bourbon Street nightclubs. His longest employer, trumpeter Wallace Davenport, was the first to take Cotton on a European tour. Though fans went wild when he played featured solos, his desire for extended road trips had long been over. In 1980 a stroke rendered his wife an invalid, and for the next seventeen years – until her death, in 1997 – Cotton attended to her every need with the loving devotion of a saint.

The last days of August 2005 brought hard times to Lawrence Cotton. Despite the threat of a major hurricane, he played his regular Saturday night gig, but during the wee hours of Sunday, August 28, he was rushed to Touro Infirmary with severe heart palpitations. When power went out, he sat out the fury of Katrina in a hot dark hospital hallway until he was evacuated to a church auditorium in Baton Rouge, where a painful kidney stone attack led to emergency surgery.

Fortunately, having had only minor wind damage to his home, Cotton was able to return to New Orleans and resume playing at the Maison Bourbon Jazz Club. At eighty, the idea of living anywhere else was never an option for him. “There’s been music all around me here ever since I can remember,” he says.

“In some cities you go to there’s no music. I don’t see how people can live there.”

“In some cities you go to there’s no music. I don’t see how people can live there.”

Donn Young

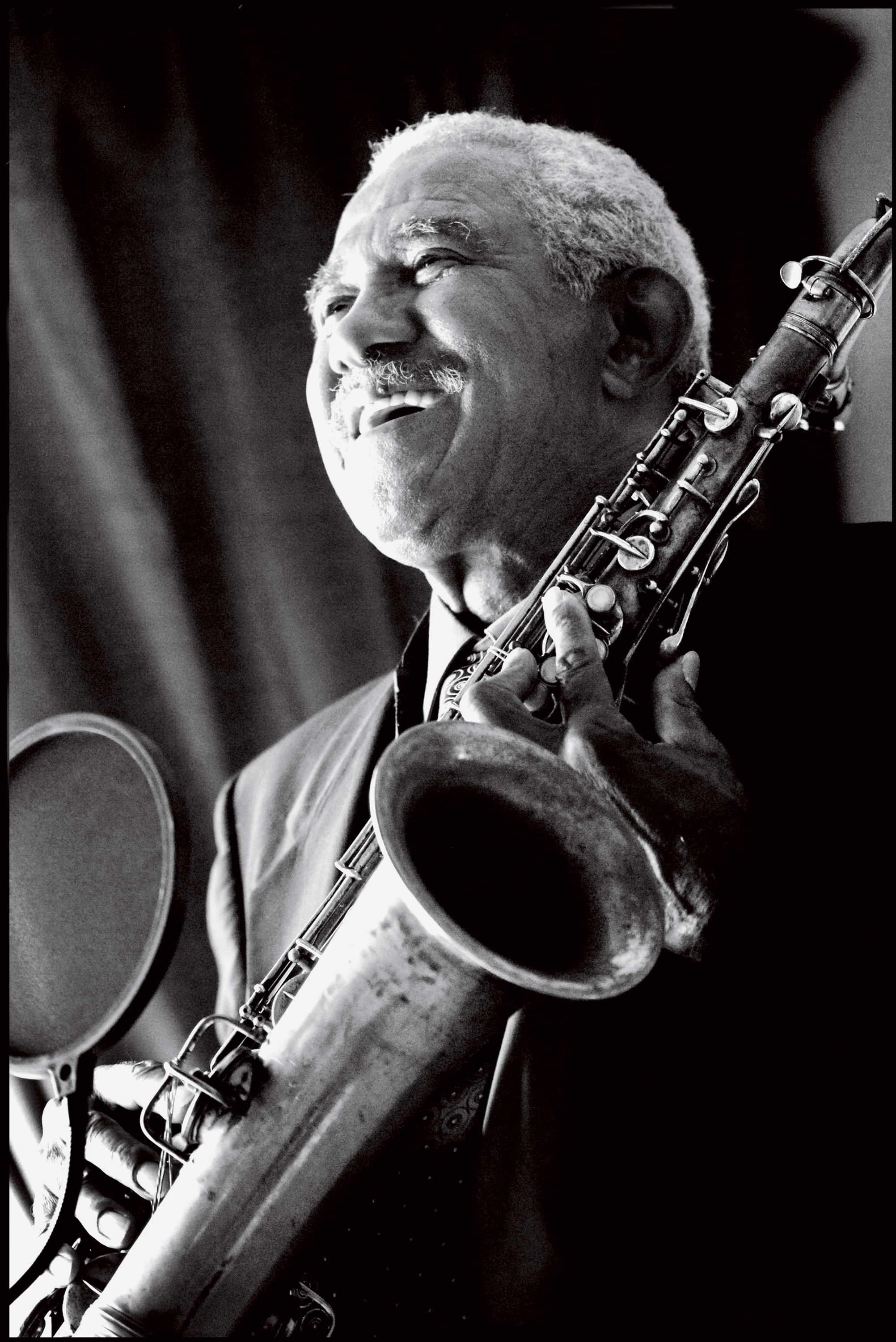

Daniel Farrow

Born June 30, 1932

Like many New Orleans musicians of his age, Daniel Farrow has performed several musical styles, including gospel, big band, rhythm and blues, and traditional jazz. He was born and has lived all his life in the Algiers section of New Orleans. After taking lessons with legendary teacher Manuel Manetta and playing in his high school band, Farrow began performing blues in local clubs.He further developed his musical skills during a four-year stay in the Air Force’s marching, concert, and swing bands.

Farrow drove tractor trailer trucks throughout the South for forty years, opting for family life and the stability of a steady job over a risky musical profession. But he also played in local R&B and big bands whenever he could. In the early 1960s he began playing traditional jazz in community parades and funerals with the Young Tuxedo Brass Band, in which he interacted with a number of early generation jazz pioneers. After retiring from truck driving he continued to play in a number of bands and occasionally appeared at Preservation Hall, where he is sometimes heard today.

The lyrical beauty and deep passion of Daniel Farrow’s saxophone tells the story of a life of extreme faith and internal strength to survive never-ending crises and hardships, of which Hurricane Katrina, which damaged his home, was just the latest. Over the last several years Farrow and his wife carefully tended to a son crippled by multiple sclerosis, who died in January. Two of his brothers have died since 2003. In 2004 his young daughter — a Boeing rocket scientist working on the space shuttle — suddenly dropped dead just months after giving birth.

For Farrow, music has been a therapeutic diversion from the pain of recent years, and while he believes New Orleans’ musicians need to be better paid, with his long-standing faith he remains cautiously optimistic about the future of his city’s music. These days his sweet saxophone can be heard at parties, brass band jobs, and jazz brunches — whenever he gets the call.

Donn Young

Peter “Chuck” Badie

Born May 17, 1925

The diminutive stature and reserved character of Peter “Chuck” Badie mask an incredible life and an amazing sixty-year music career. Badie’s introduction to music came through his father, a parade band saxophonist.

As a teen he was greatly impressed by famous New York-based big bands, but his entry into music did not come until adulthood, after he narrowly escaped a Japanese kamikaze attack on the aircraft carrier on which he was serving in the South Pacific during World War II. Badie was not physically injured — “by the grace of God,” he says — but the memory would affect him for the rest of his life. After his discharge, he began studying bass and music and was soon playing professionally in local rhythm and blues clubs.

In the 1950s Badie went on the road with popular singer Roy Brown, played in New Orleans with groups led by Paul Gayten and Dave Bartholomew, toured the world with big band legend Lionel Hampton, and played with the modern jazz-oriented American Jazz Quintet. In 1961 he became a founding member of saxophonist Harold Batiste’s AFO Records, and recorded a number of R&B hits, including singer Barbara George’s chart-topping hit “I Know (You Don’t Love Me No More).”

When Badie moved to California, he toured and recorded with legendary soul singer Sam Cooke. His throbbing bass is heard in the background of Cooke’s classic hit “A Change Is Gonna Come.” After Cooke’s death, Badie returned to New Orleans, retired from music, and, for more than ten years, worked as a waiter. Finally, in 1987, fellow musicians coaxed him to return to music, and he has played regularly ever since.

Badie’s home in New Orleans’ Ninth Ward was destroyed by flooding after Katrina. But he returned to New Orleans and, for more than a year, labored in construction with the Habitat for Humanity-sponsored Musicians Village project. Recently, he became one of the first residents to receive a new low-cost home. At eighty-two, Badie is doubtful that New Orleans will make a full recovery during his lifetime. But, a devout Catholic, he prays daily and leaves the stresses of post-Katrina life in the hands of the Lord. These days his big-toned, driving bass can be heard in a traditional jazz combo at the Palm Court Jazz Café, where he has performed for more than a decade. As Badie loves to say, “Praise the Lord.”

Donn Young

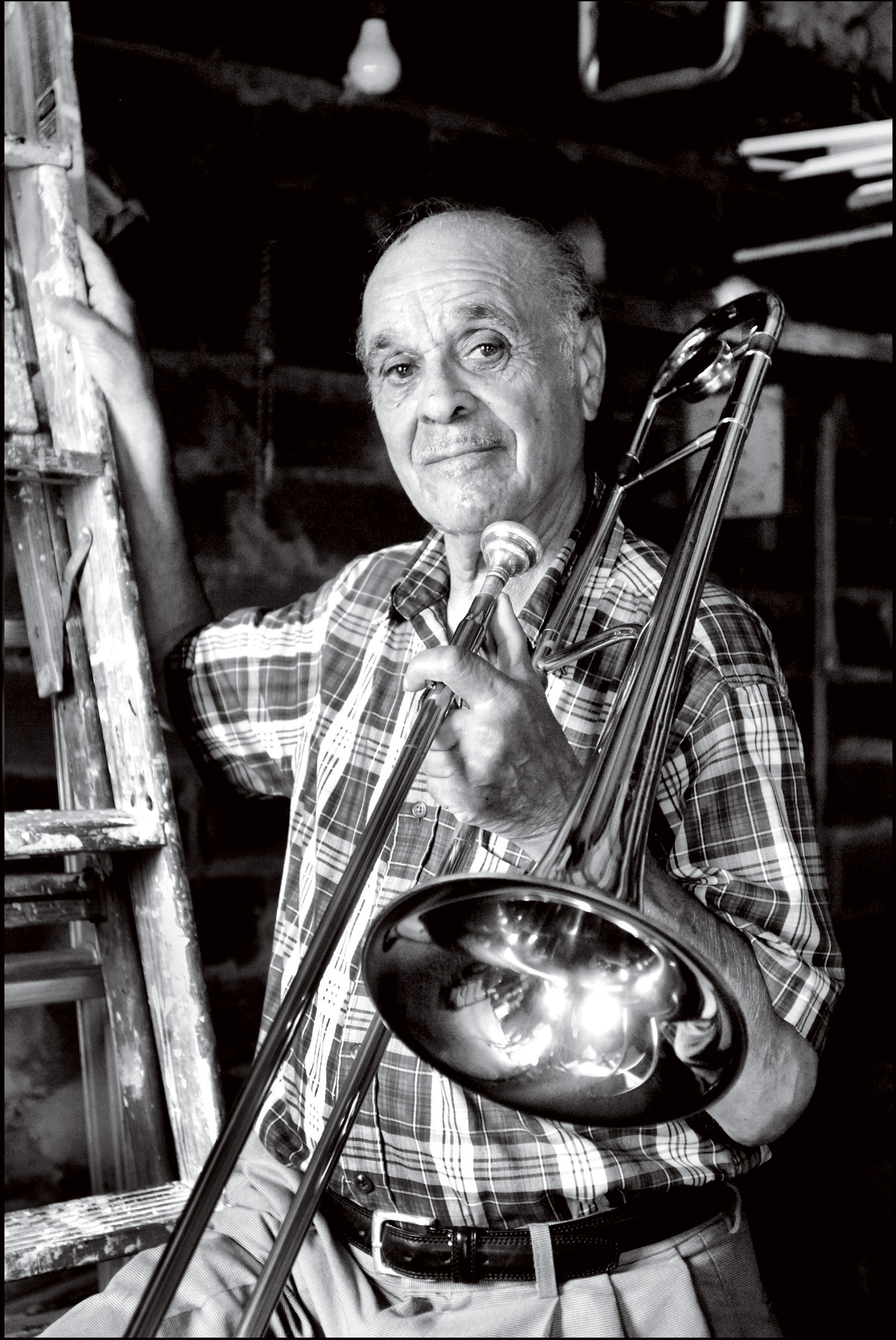

Wendell Eugene

Born October 12, 1923

Wendell Eugene took up the trombone at an early age, first inspired by seeing his uncle and brother playing in parades and jazz funerals. He was taught by his older brother, Homer, and his cousin Clem Tervalon, both accomplished trombonists. At age ten he had the memorable experience of hearing the great Louis Armstrong belting out a solo rendition of “Peanut Vendor” at a neighbor’s house shortly after the jazz legend made a classic recording of the song. At seventeen he started playing dances with trumpeter Kid Howard’s traditional jazz band, and then played in local big bands until serving in the Navy, where he had the honor of performing with Louis Armstrong.

He made several recordings, including the rousing tailgate trombone work – on Paul Simon’s 1970s hit “Take Me to the Mardi Gras”

After a brief stay in Lucky Millender’s famous big band, he returned to New Orleans to raise a family.

He taught music and played on Bourbon Street before becoming a letter carrier, a position he held for more than thirty years. Though he never stopped performing, Eugene was only able to start traveling overseas after retiring from the post office. He made several recordings, including the rousing tailgate trombone work on Paul Simon’s 1970s hit “Take Me to the Mardi Gras.” In recent years he has continued to play in small traditional jazz groups and brass bands.

Eugene evacuated just before the arrival of Katrina and spent a year and a half in Mississippi and Louisiana before returning. His house in the heavily flooded Gentilly section was badly damaged — he lost most of his possessions, including valuable instruments — but he is now back and active on the music scene and foresees a gradual revival of the New Orleans music community.

Donn Young

Thais Clark

Born May 23, 1942

While growing up in New Orleans, Thais Clark danced and took part in plays, but she didn’t sing in church or school. Occasionally, during the 1960s and 1970s, she sang along with live bands at her father’s nightclub, where she worked as a bartender. But her singing career didn’t begin until she was thirty-five, when she was hired by actor Vernel Bagneris to star in a play he wrote called One Mo’ Time. The musical — a humorous look at the perils of a 1920s touring black vaudeville troupe — called for acting, dancing, and singing; and though hesitant at first about her abilities and lack of experience as a singer, Clark proved to be a natural. With her deep, expressive voice, much in the vein of 1920s classic blues stylists such as Bessie Smith and Ma Rainey, Clark became a standout in her comedic role as Ma Reed and her show-stopping renditions of old blues classics such as “See See Rider” and “Muddy Water.” During the musical’s long off-Broadway run, and through several European tours, her authentic delivery of blues and hymns attracted the attention of traditional jazz-style bands throughout the world.

For more than twenty years now Clark has been a featured guest at festivals, in churches, and at concerts throughout Europe. She has also performed at Lincoln Center and toured China with the Lincoln Center Jazz Orchestra. In addition to the One Mo’ Time cast album, Clark has made several other recordings, including one under her own name. A recent crowd favorite is “Horn Man Blues,” a spicy number written especially for her.

After evacuating New Orleans for Katrina, she spent several months in Mississippi, Texas, and Baton Rouge, Louisiana. The storm caused wind and water damage to her home and, she says, “ruined tons of my best clothes.” Now she is concerned about the future of the local music scene: “If more clubs don’t reopen, they won’t have musicians here,” she says. “Some of the ones that are open aren’t paying musicians enough to stay in New Orleans.”

Fortunately, Thais Clark can be heard belting out jazz, blues, and hymns in her own powerful and humorous style at her regular weekly gig at the Palm Court Jazz Café in the French Quarter.

Her authentic delivery of blues and hymns attracted the attention of traditional jazz-style bands throughout the world.

Donn Young

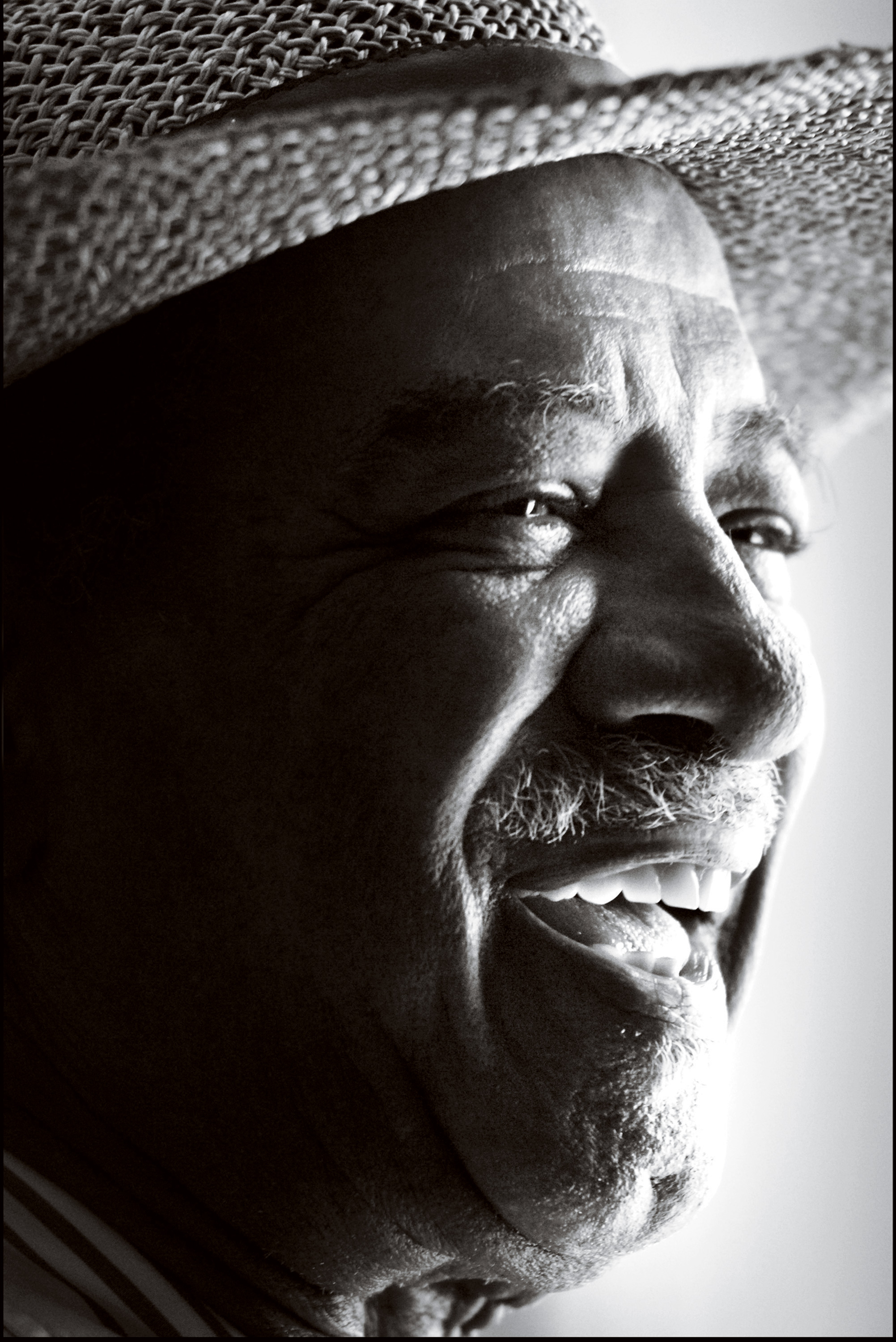

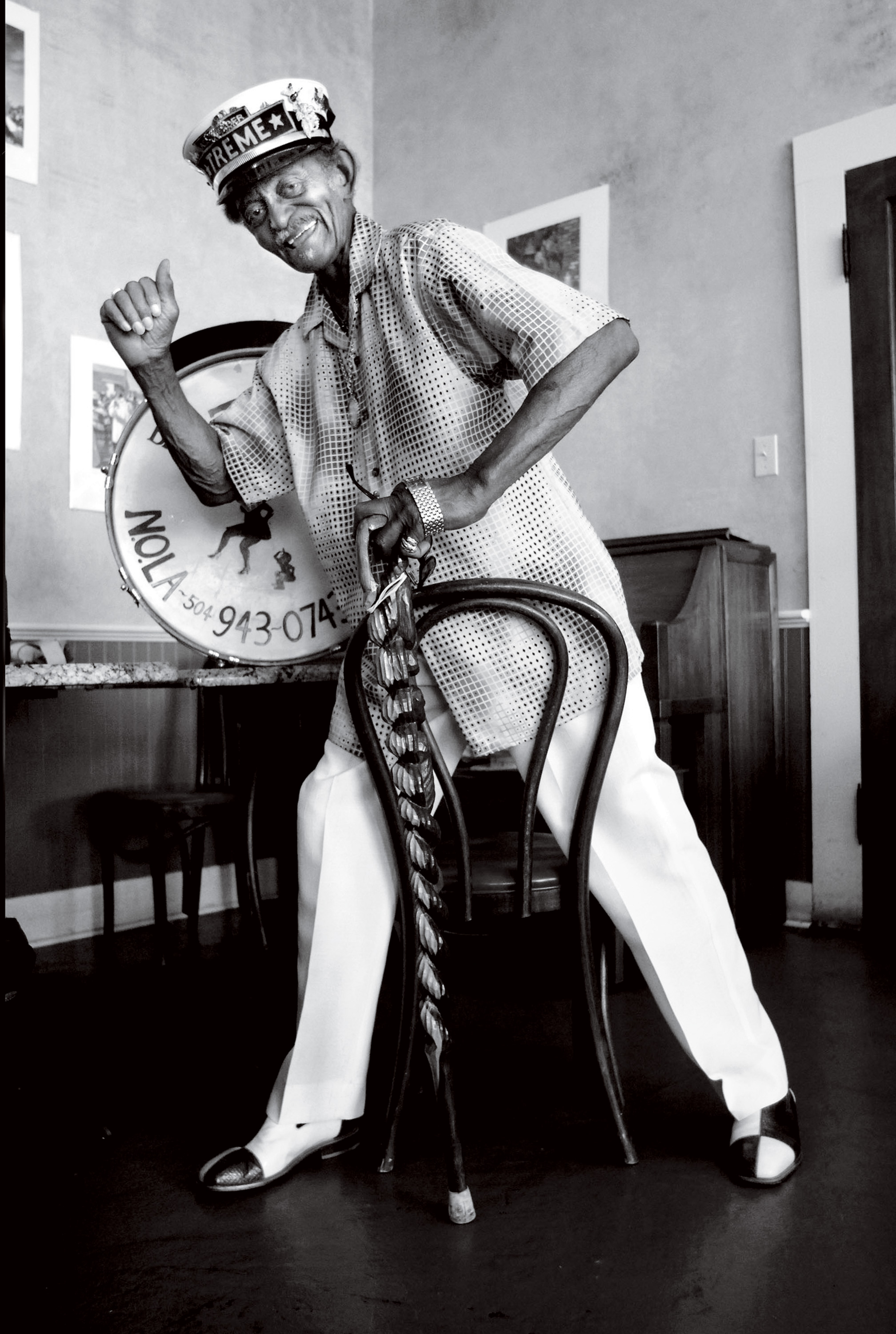

“Uncle” Lionel Batiste

Born February 1, 1931

Much of the unique nature of New Orleans has come from a series of eccentric personalities whose style and manner have inspired and influenced generations. One such character is “Uncle” Lionel Batiste. Born in the Treme section of New Orleans, which borders the French Quarter, Batiste comes from a family of musicians and good-timers fully absorbed in the pleasurable side of Crescent City life.

Growing up, he had music all around him, and at eleven Batiste began playing the bass drum in brass bands for community parades and funerals. He also learned to sing, dance, and play the kazoo. In the 1930s he and a group of friends formed the Dirty Dozen Kazoo Band, which paraded whenever boxer Joe Louis won fights.

Musical activities were more fun than profession, so to make a living Batiste worked dozens of jobs, from bricklayer to funeral home embalmer. For many years, in the evenings the twice-widowed Batiste made regular rounds of neighborhood bars and homes to socialize with friends and strangers. Always impeccably dapper in boldly colored suits topped off with matching derby and an assortment of pins and jewelry, his mere appearance, complete with his humorous retorts, was a local event.

In 1995 “Uncle” Lionel became a founding member of Benny Jones’ Treme Brass Band as bass drummer, lead singer, and assistant leader, and he has since been a popular fixture with the band locally and internationally. He is seen in the poignant funeral sequence with the Treme Band in Spike Lee’s Katrina-inspired documentary When the Levees Broke. In recent years Batiste has sung on several recordings and has been a guest grand marshal, singer, and bass drummer in numerous European jazz festival parades.

Batiste stayed in New Orleans during Katrina. He escaped being trapped in rising floodwaters by swimming to a bridge and using his bass drum to keep him afloat. He spent several months recuperating privately with family, but has since returned to being a local institution.

Batiste continues to play regularly with the very active Treme Brass Band, recently completing a successful European tour. His reappearance on the scene has been likened to the return of the spirit and soul of New Orleans.