Sporting

Hope on the Wing: A Falconer’s Story

Rodney Stotts’s journey with falconry means knowing when to let go

I. RESCUE

The bald eagle was stuck, that much everyone on the ground understood. Somehow the bird had caught its head in the cold black metal fence surrounding a Department of Homeland Security facility. Frantic, the eagle flapped its wings, brown and white plumage flashing as feathers fell out and fluttered to the ground.

Mike Jackson, a Washington, D.C., firefighter moonlighting as a security officer for the site, knew just whom to call. Tall and gaunt, the man arrived, unfolding himself from his Tahoe in his uniform of sorts: a black skullcap, an oversize white T-shirt, and baggy black shorts. He also sported a pair of Timberland boots, which he always wore with two pairs of socks, a holdover from the D.C. native’s time playing street basketball. Most folks in the surrounding metro area known as the DMV—District of Columbia, Maryland, Virginia—referred to him as “the Birdman.” Jackson simply calls him “Dad.”

The Birdman, Rodney Vaughn Stotts, is one of forty or so Black falconers in the country. Over the past twenty years, he has made a name for himself in the DMV and beyond thanks to his conservation efforts and work with raptors, including presentations and educational outreach about and with the birds—particularly with at-risk youth.

His heavily scarred hands serve as proof of that commitment, and here at the fence, he would need to be cautious. Medieval royalty once used raptors for hunting, hence falconry’s nickname “the sport of kings,” but one need only watch one of the birds in flight to understand why it’s also considered an ancient art—the graceful arc of the bird’s wing as it swoops and spins before finding and diving toward its target at remarkable speeds. Falcons often then kill their prey instantly; hawks, however, can be messier predators: When they latch onto their targets with their dagger-sharp talons, the birds tighten their grip, constricting the airflow until their prey suffocates. Sometimes they disembowel their prey, splitting open its belly and eating its innards while the animal is still breathing. Eagles like this one are capable of the same.

After surveying the situation, Stotts scaled the towering fence. When he arrived at the juvenile female—her mottled brown and white feathers not yet developed into the signature white crown—he looped his belt through the links to keep himself steady and to free his hands. Careful to avoid the eagle’s sharp talons and beak, he secured her body and then eased her neck up and out of the gap.

Stotts had quickly realized that he knew this eagle. It was Dippy, the offspring of two eagles he’d worked with years before. “Dippy” had been the nickname of Stotts’s mother, Mary Stotts. This was June 2016, almost a year to the day after Mary’s death. Stotts took it as a sign. As Dippy perched on the edge of his leather falconer’s glove, he met her eyes before swinging his arm to give her some air. The bald eagle took flight and disappeared, up, around the corner, and away from the gate.

As an old saying goes, loved ones who have died are never truly gone if someone speaks their names. So Stotts names his birds after people he has loved. When children ask about the birds—as inevitably, when they see the towering Black man walking around with a big raptor on his arm, they do—he tells them stories: about the birds, yes, but also about their namesakes. The birds are his way of remembering—where he’s come from, where he’s going, and the choices that helped him avoid the fate that befell so many of his peers.

II. REHABILITATION

“This whole thing started because I needed a pay stub,” Stotts says now with a laugh. Born in 1971 and raised in southeastern D.C., Stotts had always been fascinated by raptors, watching them in the nearby zoo and occasionally glimpsing them in his neighborhood’s scarce trees. But even more, he loved simply spending time in the outdoors—particularly at the farm of his maternal great-grandmother, Mary Alexander, near Falls Church, Virginia. Eminent domain had forced her onto a small corner of the property, but his time with her and her animals back then proved a balm from the projects.

Even so, the streets eventually proved too much of a temptation—Stotts dropped out of high school during his junior year and began selling drugs in an attempt to improve his position in life. To rent an apartment, though, he needed a W-2, so he applied for a day job. Earth Conservation Corps, an environmental nonprofit, called him back first. He started work there in April 1992, earning a hundred bucks a week cleaning up the nearby Anacostia River—a far cry from the ten to fifteen thousand dollars a week he could make pushing cocaine.

The 1990s were an especially dangerous era in D.C.; during that time, the Washington Post named the area Stotts called home “the most lethal block in the city.” He was shot in a drive-by at Condon Terrace projects. He attended thirty-three funerals in one year—among them, casualties of the drug trade, and twenty for those who would never cross into adulthood—all while continuing to work as a caretaker for the river.

The Anacostia and its tributaries, once major shipping channels, provided steam power to D.C.’s Capitol, but when its waterways became polluted and clogged in the first half of the twentieth century, it was abandoned. Corps members spent their days lugging plastic bottles, old tires, and even mattresses and car engines from the roughly five-mile stretch of the struggling tributary called Lower Beaverdam Creek.

His friends’ deaths, and then a two-year prison sentence for dealing drugs, forced Stotts to evaluate the man he wanted to be. Or as one of his tweets would later read, “Google dont have the route to your future. Map your own destination.” He takes that mantra seriously. He could clean up the river, he decided. He could clean up his life. Not long after he was released in 2003, he rejoined ECC, this time as a teacher and mentor: He knew where to find the at-risk youth the nonprofit hoped to reach—he was coming from the same neglected area.

As the river became cleaner, wildlife returned. Stotts saw his first great blue heron on that water. ECC had begun reintroducing bald eagles there in the mid-nineties—the last pair of adults had previously left in the 1940s, America’s capital no longer hospitable to America’s symbol. Around the same time as the reintroductions, the group also started caring for injured birds, and using them to demonstrate the importance of cleaning up the Anacostia. That’s how Stotts met Mr. Hoots.

The Eurasian eagle owl, at one time an entertainer at an amusement park, had been discarded when he injured his wing and made his way to ECC, where he became the first raptor Stotts ever held. The bird compelled him, and over the next decade, Stotts would think often of the way looking into the bird’s eyes had tugged at his soul.

Eventually, ECC’s endeavor with birds expanded into a full-fledged venture called Wings Over America, an environmental education and falconry rehabilitation program in Laurel, Maryland. The initiative aimed to recruit teens to build aviaries and learn how to handle, feed, and care for the raptors in order to cut the recidivism rate. But Stotts soon had bolder dreams: “I want to keep youth from being incarcerated in the first place.”

Working with impressive, healthy birds, he thought, would help him to reach more at-risk kids. In 2011, he secured a sponsor, a master falconer—Suzanne Shoemaker, who operates the Owl Moon Raptor Center in Boyds, Maryland—to provide the mentoring and teaching required before anyone can become an official apprentice and, eventually, a master falconer himself or herself.

Tending to raptors requires following a strict code of ethics and attaining the proper licenses and permits. That’s partly because the art isn’t just for sport or show: Falconry also helps conserve species. In the wild, close to 75 percent of raptors that hatch will die during their first year. When a falconer captures a flighted bird to train, it must be less than a year old. Capturing and caring for a raptor ensure the bird survives its first year. Many falconers will trap a bird in the fall, hunt with it through the spring, and then release it, healthy and in peak physical condition.

As Stotts began working with the Wings Over America raptors and teens, parallels emerged. Earning birds’ trust takes time. Some take days. Others, weeks. The same goes for humans. Both, too, can use a little help to survive the juvenile stage. Birds don’t exactly take direction, and to a certain extent, neither do teens. All falconers can do is provide nourishing food, a safe habitat, and security, but any time they free-fly a bird, there is always the risk it will leave. Falconers can ask their charges to execute commands, but the raptors decide whether they will honor the request. A hawk might refuse to come back, flying off into the woods, untraceable to its handler.

For many of the young people Stotts meets, particularly ones from the inner city, their experience with the raptors marks their first time engaging directly with wildlife. Stotts takes immense pride in showing them that there is more to life than the flashy glamour of jewelry and fast cars, and the illusory stability of drug money he knows all too well.

The outdoors provided Stotts with an escape hatch from the life that killed so many of his friends. He emerged damaged, but still breathing. Now the birds offer everyone, including him, a connection to something bigger, something awe-inspiring. As the children put on leather gloves and the birds leap onto their hands, the raptors remind them that they could grow up to live lives of wonder. That there is another flight path. And perhaps any hope that soars will help combat the fatalism the streets seem to breed.

Stotts has found his own ways to deal with the fallout from that life. Once he earned his official falconry apprentice license, he went to the woods near Rosecroft Raceway, across the Maryland line from where he grew up, and trapped his first bird, a female American kestrel. He named it Monique, after a crew member who was raped and murdered while staying in Houston to work on an ECC project. More of his fellow Corps members have died, too. Gerald Hulett, nicknamed “Tink,” was murdered in 1996. Benny Jones was murdered just weeks later. James Medley passed away a few years after that. Stotts has named birds after them all.

His roster of Harris’s hawks over the years has also paid homage to loved ones: Nanny and Gloria, named for his aunts; Chuck, for his older brother, Charles; Squeal, after a childhood friend, Billy Morris. And Agnes, whom Rodney calls his “heart bird,” a gift from his trusted friend Agnes Nixon, the late celebrated soap-opera creator and mother of Bob Nixon, who founded ECC. Agnes stands out, her rust-red plumage and bigger size distinguishing her from his other hawks. And because she hails from the Sonoran Desert in Arizona, he can never release her into the D.C. wild; she and Stotts will be together for the duration of their lives.

Perhaps this is why Stotts is so affectionate with the animals in his care, why he treats them so tenderly. They are more than the formidable predators the outside world sees and fears. They’re smart, strong, and fierce, demanding patience and respect. They are family.

III. REDEMPTION

Around 2017, Stotts began to look for a way to further spread his wings. Since ECC’s raptor program works solely with children in the care of D.C.’s Department of Youth Rehabilitation Services, he often had to turn down opportunities to introduce the birds to folks from different walks of life. He decided to create a group called Rodney’s Raptors, with the motto HELPING OUR YOUTH SOAR. Now he hits the road giving presentations to anyone who asks: public schools, Boys & Girls Clubs, the annual Monacan Indian Nation Powwow outside of Lynchburg, Virginia. Stotts has even worked with the Make-A-Wish foundation, fulfilling the dreams of children who want to meet his birds. Otherwise, he shuttles between the educational programming he runs at Wings Over America’s Laurel campus and a seven-acre property he owns in Virginia that he’s named Dippy’s Dream, where he’s building a sanctuary—not just for birds, but also a donation-funded retreat for humans who need the peace and refuge and healing from trauma and grief that he’s found in the natural world, too.

Discussing and spending time around the birds, Stotts has learned, opens a gateway to converse with the people he meets about other topics: conservation, habitat destruction, animal migration, climate change. He’s extended the reach of his message, too, by cowriting a recently released book called Bird Brother: A Falconer’s Journey and the Healing Power of Wildlife, and by participating in a documentary, The Falconer. A mural in Sacramento, California, even depicts his face, along with a likeness of Agnes the hawk.

Closer to home, many of Stotts’s eight children and eleven grandchildren also embraced falconry. He sponsored his son Mike, who will soon sponsor his younger brother. Quick to don a glove or trek through undergrowth to watch their grandfather fly his birds, the youngest get excited by the whistles, clicks, and chirps Stotts uses to communicate with his raptors. He says he can’t wait until they grow up so that he can be their falconry sponsor, too, creating generations of Black bird lovers committed to the environment and education. Perhaps he cannot ensure his progeny’s happiness, but he can give them this: a skill set that can help them better understand life. That might help them survive.

The city, after all, still teems with pitfalls and dangers. One day this past July, Stotts received a phone call. There had been a shooting. The public learned of the murder from a news release: “The decedent has been identified as 32 year-old Devin Denny, of no fixed address,” the D.C. Metropolitan Police Department wrote. Information about the murder is scant; the word decedent is emotionless, with no indication of who the person was, or had the potential to become. But Rodney Stotts knows, because now he must grieve one of his sons.

In October, he named a barn owl Devin.

IV. RELEASE

By the time you read this, the leaves will have changed and freed themselves from the trees, and Stotts will be out trapping raptors. He will work the woods around his house, walking through the woodland prairie at the edge of his property, the dry grass crunching under his boots. The birds will be easier to see, and with winter approaching, they will be hungry.

He will set down his trap, a homemade dome-shaped wire-mesh cage, and put some live bait in it—a couple of mice, maybe a rat, or perhaps even a small bird like a pigeon, anything with movements that would snag the attention of the bird of prey he desires. It might take only minutes, it could take days. But eventually Stotts will get what he came for.

“It will be a red-tailed hawk,” he declares, certain, knowing.

Precious few things make sense in the fog of grief, but he finds purpose in this pursuit. Red-tailed hawks’ plumage changes color as the birds mature. An adult, called a haggard, sports a bright red tail. Juveniles, a white belly band and a muted brown tail. Stotts will look up, watching the trees until he finds a suitable contender. Once he has the bird he’s after, the pair will head to the aviary.

They will begin to work together, and then eventually, Stotts will have to let the bird go. But before he does, he will commence a ritual he began years ago. When a bird is ready to be released, Stotts posts the news on Facebook and invites followers to send in prayers for their loved ones, or names of the deceased that they would like remembered and said out loud, or perhaps intentions that they have in their hearts. He compiles those comments into a list.

“I want to say a prayer for Mary Dutton, her daughter, and her pets,” one of his earlier release videos begins. “Antonio Carpenter, Pete and Fran Miller…” The names keep coming at a steady clip, until he has read through them all. Then he opens the cage. The hawk looks around before stepping forward, then, filled with prayers and memories and hopes, it flies away.

Stotts will look after it, and then up, and then up again and again—for birds, for signs, for confirmation his life is not a reverie; it’s his, and he made it.

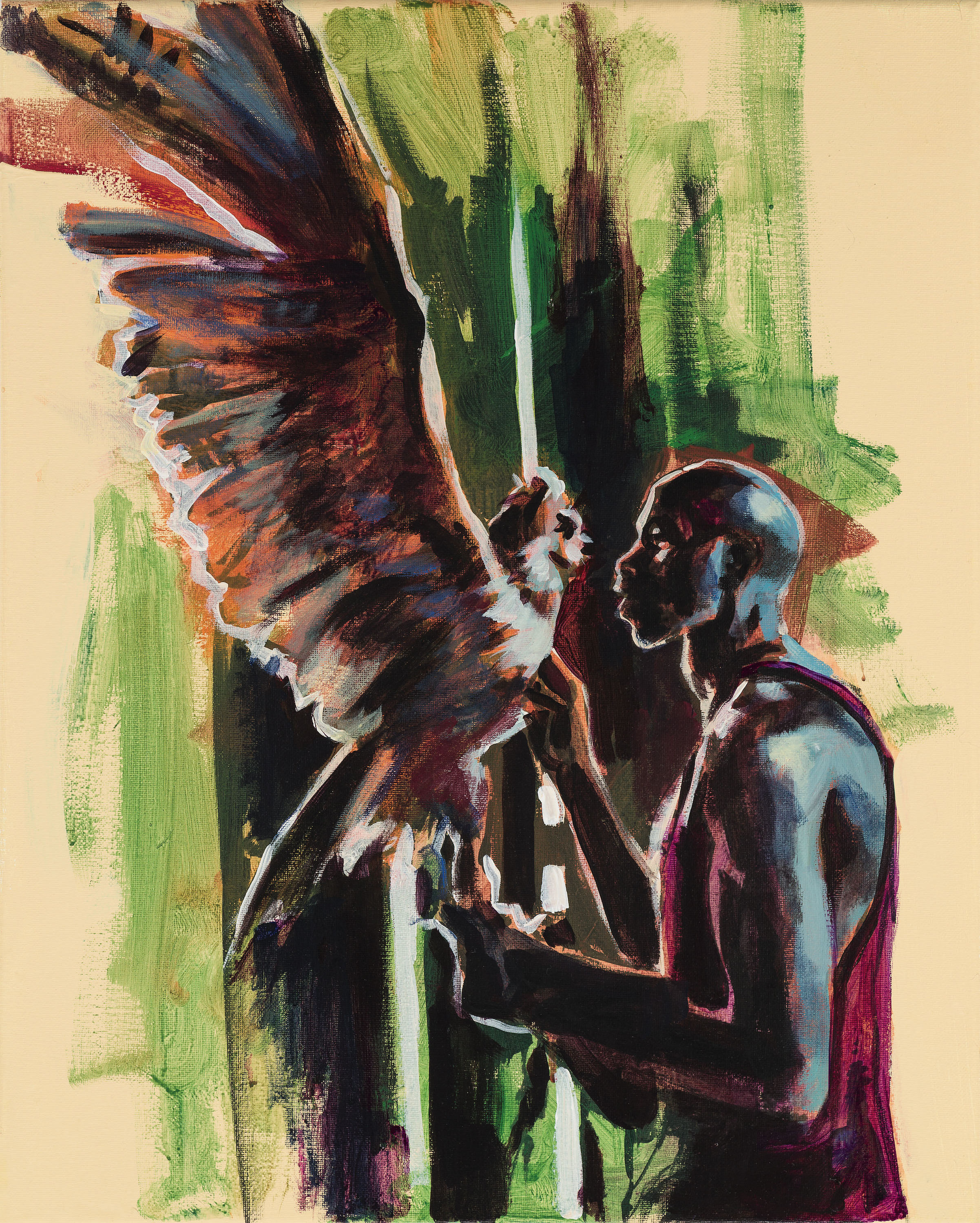

Paintings photographed by Travis Grissom