“This place was, I think, scary in a certain past life.”

Gaston Farmer makes this somber declaration as we gaze at the skeletal chassis of an ancient sedan, rusted beyond recognition and bizarrely come to rest on a shady slope on Lookout Mountain, a short drive outside and some 1,300 feet above downtown Chattanooga. How the wreck ended up here, on what’s now a nature preserve, is anyone’s guess. Farmer, who is twenty-nine, is Chattanoogan both by pedigree (his great-great-grandfather served as mayor in the 1880s) and by inclination: A devoted mountain biker, backpacker, ice climber, and fly fisherman, he once pedaled the Continental Divide from the Canadian Rockies to Mexico. He and I have just scampered up a steep rise from the plunge pool of Lula Falls, a rapturous 110-foot-high cascade that’s lured visitors for generations: Cherokee families, bear and wolf trappers, Union soldiers, coal miners, society ladies in wide-brimmed hats photographed as they merrily picnicked just a few alarming inches from the falls’ sheer drop-off. Decades ago, Farmer tells me, these woods also provided a backdrop for seamier encounters—thieves stripping stolen cars and rolling them off bluffs, and a grisly murder of two lovestruck teenagers in 1963.

In recent years, though, a transformation has taken hold. Today, the Lula Lake Land Trust—which helps conserve about 12,000 acres on the mountain and employs Farmer as its community outreach coordinator—is one jewel in a chain of restored and protected landscapes in and around Chattanooga, part of what makes the town a sort of Emerald City for outdoor adventure. The trust has laid out nearly fifty miles of singletrack for hikers and mountain bikers; is nursing “a living laboratory” of American chestnut saplings crossbred for blight resistance in hopes of reviving the tree that once dominated Eastern forests; and is spearheading a crusade to protect hemlock trees, a keystone species that shelters more than a hundred types of animals, from invasive insects. Green credentials aside, the place is a showstopper. Following the creek upstream from the falls along a former railbed, we arrive at Lula Lake itself, a nearly forty-foot-deep pool fed by a smaller but no less captivating waterfall. Sunbeams light the trees and dance on the jade-colored surface. Overhanging sandstone cliffs shadow the opposite bank. It’s a cathedral of light and stone and water.

Chattanooga has enjoyed a roaring comeback of its own of late, a much-told story that, as I witness during a four-day visit, continues to sprout new chapters. In 1969, Walter Cronkite trumpeted a government report that labeled the slumping city as America’s dirtiest. Thanks to unchecked emissions from coal furnaces, railroads, and factories, drivers flicked their headlights on in daytime to cut through smog, and the air tasted of sulfur; in the 1980s alone, the city lost a tenth of its residents. But in the next decade, it began giving itself a head-to-toe makeover. The world-class glass-peaked Tennessee Aquarium jump-started the turnaround. The adjacent Riverwalk and connecting greenways now invite cyclists and strollers to trace the bank of the broad Tennessee River for nearly twenty miles, switchbacking up to the Hunter Museum of American Art and a thriving bluff-top arts district, near the popular and car-free Walnut Street Bridge.

Along the way, the city has acquired a habit of reimagining old spaces rather than bulldozing them. Consider some of the downtown lodging options. At Common House, a former YMCA built in 1929 in the now-fashionable Southside district, a half dozen snug rooms and a spacious suite occupy the top floor of a sort of clubhouse for professionals that includes co-working nooks, four bars, a billiards room, and a heated saltwater pool. The venerable Read House, which has put up the likes of Al Capone and Winston Churchill, underwent a $28 million sprucing-up three years ago that went all in on art-deco flourishes that hark back to its Jazz Age heyday. Murals brighten old redbrick buildings, and the city’s vaunted gigabit-per-second internet lures start-ups and work-from-homers. Best of all, I’d argue, it’s a fun-hog playground few cities can match, with dozens of nearby trailheads and overlooks, and bike-share racks popping up all over. Right smack in town or close at hand, you can float a mighty river, camp on a wildlife-sanctuary island with a great blue heron rookery, and belly-crawl through an underground cavern: the full Tom Sawyer.

“It’s just big enough to be a city, and not any bigger,” says Enoch Elwell, a muttonchopped New Jersey native who attended Covenant College, a tiny school atop Lookout Mountain, and stuck around, smitten with Chattanooga’s “culture of possibility.” He’s now “director of vision” at Co.Starters, his firm that nurtures entrepreneurs and preaches Chattanooga-style revival to towns in places as far-flung as New Zealand. I’ve met up with him to take a peek at one of his side projects, a pair of rentable tree houses called Treetop Hideaways, tucked in a secluded Middle Earth patch of woods on a lower flank of Lookout.

Once we arrive, Elwell shows me inside one of them, called Elements, which embellishes its storybook setting with decadent touches: black walnut floors and poplar beams; a loft with twin beds and large skylights for stargazing; and a walk-in shower with five showerheads, digital temperature control, a heated floor, and a towering beech tree rising next to it through a glassed-in partition. This being Chattanooga, the tree house also has gigabit internet, and, perhaps redundantly given the surroundings, its own alluringly woodsy room spray (“our own specialty mix of essential oils,” Elwell says). A stream gurgles melodically just out of sight. This all strikes me as not a bad place to bunk.

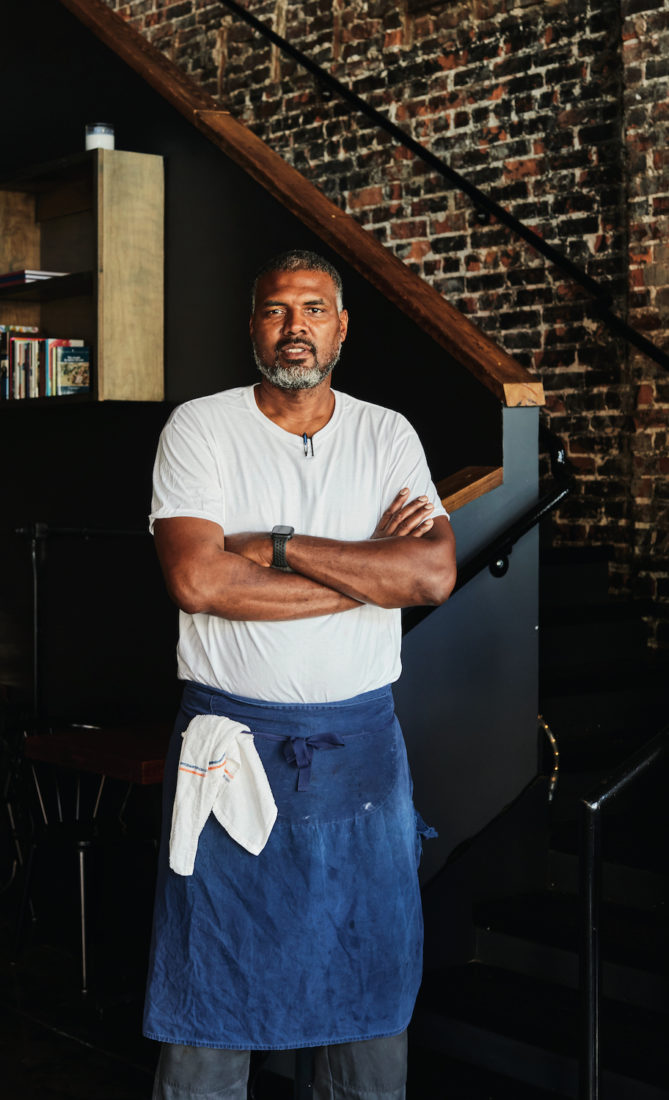

The latest wave of Chattanooga’s renaissance has also given rise to plenty of intriguing restaurants, and I take it as a personal challenge to sample as many as possible, an adventure unto itself. After the tree-house tour, Elwell tips me off to Calliope, which chef Khaled Albanna, who was born in Egypt and grew up in Jordan, opened a few days earlier just outside town in Rossville, Georgia, inside a meadery called Flora de Mel that offers a dozen meads on tap. I fearlessly pair hummus and braised lamb shoulder with peanut-butter-and-jelly mead (a better combo than you might think). I conquer a BLT with house-cured bacon at Main Street Meats, on sourdough baked right next door. Navigate a ramen-like bowl of brisket meatball yakamein at Neutral Ground, where Kenyatta Ashford, a New Orleans native, riffs on hometown standards like po’boys and Ghana-inspired specialties like West African Red-Red. Face down garlicky egg pie and buttermilk biscuits at Syrup and Eggs, a welcoming botanical-wallpapered dining room adjoining the boutique Dwell Hotel. At St. John’s, one of the city’s go-to fine-dining spots on Market Street, I brave a dish of roasted teres major and braised cheek on red pepper grits. I summit the riverfront Edwin Hotel, arrive at Whiskey Thief, its fifth-floor rooftop bar, and triumphantly sip a Chattanooga F.R.H., a boozy concoction of fig-infused high-malt whiskey and rye, both distilled less than a mile away. I put on five pounds and regret nothing.

My favorite meal of the trip involves a nicely charred wood-fired pie picked up at Lookout Mountain Pizza Company, but it’s the ambience that lingers in my mind. By now my wife has joined me in Chattanooga, and on a wise tip from a local, we ferry our dinner up the road along the plateau to a strategic perch atop a dizzyingly high bluff. Not surprisingly, this area is also a mecca for hang gliders, who often launch from this very ridge, home to the Lookout Mountain Flight Park; incredibly, one accomplished glider back in the nineties touched down 154 miles from this spot. This evening, ultralight planes are towing several gliders, one at a time, high into the air from a wide green clearing in the valley far below, until the hang gliders disconnect to soar on their own untethered.

We watch as they slowly wheel and bank and ride the thermals like white-winged eagles, the mountain ridges resembling dark green waves in the fading light. Other spectators pull off the road to take in the show. The sun reddens like a campfire coal. A bottle of wine appears. All too soon, the sun sinks into the mountain swell beyond the valley, a sliver of moon rises, and we stare out into the dusk at the flying humans below.