When I was growing up, during those long desert years before I looked old enough to sneak into bars, movies were the thing. No, they were everything. First, there was the drive-in on the highway and the Paramount downtown, which had once been the local opera house—when it was misguidedly demolished in the late sixties, it was rumored that jewels and actual tiaras were discovered in the rubble. After that came the Plaza and the Cinema, which, excitingly, housed two separate theaters. My best friend, Jessica, and I never missed a weekend in one or both, which meant that we saw pretty much every film released in the 1970s—sometimes two or three times, depending on how long they lingered in town. We were variously in love with Paul Newman, Robert Redford, Dennis Hopper, James Coburn, and the dude who played Billy Jack. But we would watch pretty much anybody in anything, including the rats in Willard, a movie I still can’t believe I let Jessica con me into sitting all the way through. My nightmares about rats continued to visit me until I was in my twenties and finally got a cat. But I digress.

I come from a long line of movie lovers. My father can still quote lines from Casablanca and The Treasure of the Sierra Madre, as well as (way more unexpectedly) Wilford Brimley’s entire closing speech in Absence of Malice. My mother’s many televisions are invariably set on TCM or AMC from dawn to way past dusk while the sound ricochets around the house because she refuses to wear her hearing aids, but I can think of far worse channels to have to overhear (for those, I head to my father’s inner sanctum).

Obviously, not all the movies we watched were Southern, but there were plenty set in the South, including Flipper, which was filmed in Key Largo and which I saw at the drive-in with my parents. I loved Flipper for the simple reason that the intrepid dolphin did not die, though he came pretty damn close. For a while there, it seemed like I would forever be made to watch some beloved animal meet a tragic end: Bambi’s mother, Old Yeller, Thomasina (well, she gets another life, but still). The earliest “major” Southern film I remember seeing was Gone with the Wind. I was maybe eight and it was having one of its many rereleases on the big screen. My grandmother, as a point of education, took me to see it at the Belle Meade Theatre in Nashville, where my mother had watched it from the “Coloreds Only” balcony with her nurse Anna Davis decades earlier. Even at that young age, I could not for the life of me understand the allure of the eternal milquetoast Ashley when Rhett Butler was, you know, right there. But what I remember most is that for the rest of the summer, whenever I had a sulky, entitled, or remotely spoiled moment, my grandmother would call me “Scarlett” in her sharpest voice, so I didn’t like Scarlett much either.

There are plenty of other iconic Southern films, from Steel Magnolias, penned by my brilliant friend Robert Harling, to Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, in which Paul and Liz look fabulous, but I could never get past the accents (really? Burl Ives? He was far better cast as Sam the Snowman). Then there’s To Kill a Mockingbird, of course, and A Streetcar Named Desire, and, yes, Deliverance, but I just can’t with that. The following List of Reed’s Southern Films, Part I, is far more idiosyncratic, pulled together from Jessica’s and my obsessive years, along with the occasional deep dive with my mother into her fave old movie channels. I am not necessarily making a case for their greatness, just their deeply intrinsic Southernness, which is not always, I warn you, a good thing. Also, a nostalgic note: I am a Netflix/Amazon/BritBox/You-Name-It binge-watcher like nobody’s business. But man do I miss the feeling of being in the actual theater that writing about almost all of these pictures conjures up. There is something just not right about mixing “buttered” popcorn with Raisinets and drinking giant-sized sodas at home. They are much better enjoyed in the dark with some compelling giant-sized action unfolding in front of you.

Oh yeah, one last thing: Our cover for all those nights when we finally did manage to get into the bars was the fairly believable lie (given our long history) that we were at the Cinema or the Plaza, and a surprise late-night sneak preview (which only ever happened once in my entire moviegoing career) was almost always involved, thereby stretching our curfew. The movies continued to be my salvation even when I didn’t actually attend them.

Frogs, 1972

This would have been as terrifying to me as the aforementioned Willard, but it is redeemed (if you can call it that) by the incredibly sexy presence of the young Sam Elliott and the fact that it is a veritable textbook on reptiles and amphibians (including an Argentine black-and-white teju—who knew?). Billed rather high-mindedly as an “eco-horror” cautionary tale (a bunch of bad pesticides are involved, prompting the tagline “TODAY—the Pond! TOMORROW—the World!”), it is actually an insane piece of high Gothic mischief starring an ancient Ray Milland as the taxidermy-loving, wheelchair-bound patriarch of an Old Southern Family and master of a dog named, naturally, Colonel. Ray is intent on going through with his Fourth of July birthday celebration even though pretty much everybody around him is getting eaten alive (and I am not making this up) by: leeches, tarantulas, a cottonmouth, a rattlesnake, and a loggerhead turtle. And that’s not even the whole list. Finally abandoned by the few left standing (all except poor Colonel, that is), Ray has a heart attack brought on by the cajillion frogs breaking into his house. After the credits roll, we see them hopping all over his body, and then, because it’s not remotely over the top enough yet, an especially disgusting animated version pops up with a human hand in its mouth. I think we actually saw this twice, possibly because Sam has more than one scene without a shirt.

Walking Tall, 1973

I could not possibly leave this movie off the list since it stayed in our hometown for, I swear, six whole months, paralyzing the Plaza and forcing us to watch it maybe a dozen times. Joe Don Baker stars in the semibiographical tale as Buford Pusser, a sheriff who vows to clean up McNairy County, Tennessee, shutting down gambling dens and illegal distilleries armed primarily with the four-foot hickory club that was his trademark. Buford was inspired to run for office by the fact that bad guys beat him up, knifed him (requiring more than two hundred stitches), and left him for dead with the tacit blessing of the corrupt incumbent. Joe Don looked pretty good, but I can tell you that the real Buford didn’t fare so well. Such was the local popularity of his story that he made an appearance at the Chevrolet dealership and passed out signed ax handles (a poor imitation of the film’s murderous weapon). Jessica and I were all for brave old Buford and everything, but his appearance there among the Oldsmobiles and Chevys left us with the strong sense that some things are better left on the big screen.

The Last Picture Show, 1971

This seriously great film directed by one of my heroes, Peter Bogdanovich, is based on the seriously great novel by another of my heroes, Larry McMurtry. Shot in black and white with a soundtrack dominated by Hank Williams, it was an actors’ showcase. I mean, who could possibly stay away from a flick starring Timothy Bottoms, Jeff Bridges, Ben Johnson, Cloris Leachman, Randy Quaid, Eileen Brennan, and Ellen Burstyn? It was also the debut of Memphis girl (and Bogdanovich’s future great love) Cybill Shepherd. There is a whole bunch of good stuff in this movie, but I may love it most for the immortal words of Ben Johnson (as Sam the Lion, movie theater, pool hall, and café owner), which I find myself repeating all too often: “I’ve been around that trashy behavior all my life, I’m gettin’ tired of puttin’ up with it.”

Hush…Hush, Sweet Charlotte, 1964

This twisty—and decidedly twisted—thriller was meant to reunite Joan Crawford and Bette Davis, who had a huge hit together in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane?, but Bette was furious with Joan for a host of complicated reasons, mostly involving the Oscars (Bette was nominated for Baby Jane but lost to Anne Bancroft and then Joan turned up and accepted the absent Anne’s statue, a story line on FX’s recent Feud). Anyway, after all sorts of slights, including Joan’s not being met at the airport in Baton Rouge, near where the movie was made, the star took to her bed and was replaced with Olivia de Havilland. Therein lies the deliciousness, at least for me—angelic Melanie (another of my least favorite GWTW characters) is here an evil, duplicitous bitch who nearly succeeds (with the help of ever smarmy Joseph Cotten) in driving her already fragile cousin Bette insane to get at her hefty fortune. There’s a brief appearance by my man Bruce Dern, who plays Bette’s long-ago lover (before both his head and his hand get cut off, which the locals wrongly attribute to Bette herself), and a longer one by my beloved Endora, a.k.a. the brilliant Agnes Moorehead, before Olivia throws her down the stairs. Bette finally pulls it together and literally knocks off Joe and Olivia by pushing an urn off the second-floor balcony of Houmas House, a nineteenth-century Greek Revival pile on Louisiana’s River Road, where all the outdoor scenes take place. (It is open to the public, and I highly recommend a visit so you can see the real urn for yourself.) Though Bette is very good, a case could be made that the house is the real star—for all its craziness, the film is beautifully shot, and the scenes on the grounds are especially gorgeous.

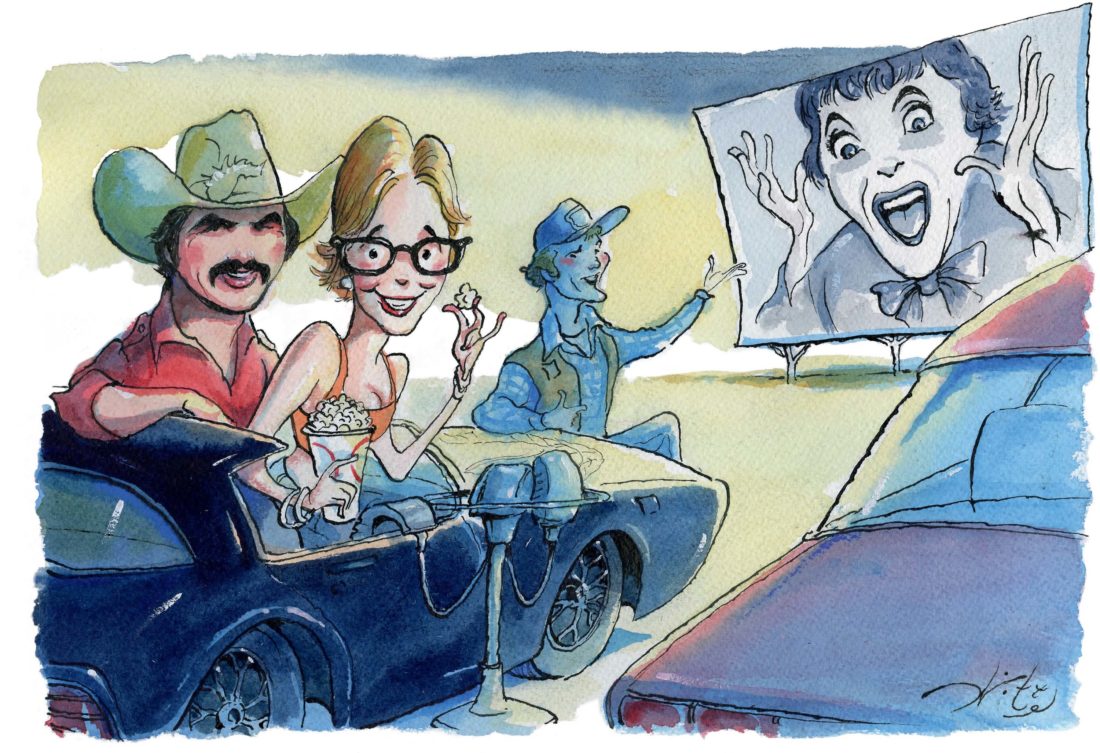

Gator, 1976

When it comes to movies starring Burt Reynolds and involving a bunch of fast cars and Jerry Reed as costar, a whole lot of folks would say that the ne plus ultra is Smokey and the Bandit, the second highest-grossing movie of 1977, just behind Star Wars. As it happens, I spent a lot of time with one of Smokey’s producers, the Memphis native Mort Engelberg, during Bill Clinton’s 1992 campaign (he produced the bus tour through the Midwest, which required lots of trucked-in hay bales), and I liked Mort a lot, but I disagree. Strongly. In Gator, Reynolds’s directorial debut and the sequel to the excellent White Lightning, Reynolds is on the side of the good guys and even gets a highly unlikely girl, stunning TV news reporter Lauren Hutton, who can’t actually act, but who cares. I knew the leggy Hutton well from years of perusing my mother’s Vogue magazines, and I’d much rather watch her seduce Burt than, say, the perky Sally Field. And who can blame her? Reynolds is irresistible primarily because he maintains my favorite quality of always seeming to be laughing at himself even in more serious roles (well, maybe not in Deliverance but again, I can’t with that). During this fruitful era, some critic described Burt not all that kindly as King of the Randy Redneck action film, or words to that effect. And I’m like, What? That’s a bad thing?