Bart Knaggs cannot contain his giddiness after a long morning fly fishing with a buddy on the Llano River in the Texas Hill Country. Not because of the fish they caught, but because of the fish they didn’t. “We came through the rapids, and right away there’s this big bass”—he gestures down to the river from where he’s standing next to his hilltop home. It might have been the catch of the morning, Knaggs says, and his friend thought he had it—but then cried out as it dropped off the line. Knaggs throws his head back and laughs at the memory, one of many little moments of fun and friendly competition that he’s collected on this river over decades angling here.

Photo: Wynn Myers

Zooey, the family dog, beneath four of Bart Knaggs’s prized fly rods, including his favorite, a custom-built 4-weight (second from top) that was a gift from Orvis CEO Perk Perkins.

Knaggs is a fifty-year-old Austin entertainment and hospitality entrepreneur who, among other things, founded the Austin City Limits Music Festival and co-owns several popular restaurants and hotels. He’s also a guy who can justifiably claim fishing superiority over most anyone on this stretch of the Llano, about two hours from Austin—he’s been exploring the area ever since he and his younger brother started fishing there as kids. In his twenties, he frequented a fly-fishing lodge owned by the late Texas grande dame Raye Carrington, a close friend of the former governor Ann Richards. More recently, as he built his business empire, he and his wife, Barbara, began to scout locations to one day build a weekend home.

BONUS PHOTOS: Click to view more images from this story.

Photo: Wynn Myers

One of several outdoor areas.

In 2008, Knaggs landed a forty-eight-acre riverfront parcel and erected a bare-bones fish camp, an open-air structure with a rain shower, a rudimentary kitchen, and a metal roof. For four years, he came out with Barbara and their three girls, or sometimes just his buddies, to play on the river and sleep on cots. They walked every foot of the property and, after choosing the perfect site, finally built their dream house in 2014. A glass box overlooking the Llano, the house both is an anomaly in this rugged country and provides an elegant way to live in harmony with the surroundings. There’s nothing like it for miles.

“It looks supermodern, but when you’re here, you just feel the space—you almost don’t feel the house,” Knaggs says as he and Barbara settle in on the wide concrete patio, while their youngest daughter and a friend make off for a nearby swimming hole. “How do you add a house and make the place more peaceful? I wouldn’t have thought you could, and yet this does it.”

To pull off that trick, Knaggs enlisted Michael Hsu, an Austin architect. A fellow fisherman, Hsu started camping on the property with Knaggs, and the two talked about what it felt like to be there and how a house might channel that feeling.

Whereas much of the Hill Country closer to Austin is more pastoral, with rich brown soil and wildflowers punctuated by big oaks and limestone cliffs, the area around the Knaggs home more closely resembles West Texas, with sandy dirt, fewer trees, and a lot of low prickly pear and mesquite. The river runs over a granite bed, which means there’s very little silt and the water flows clear. “You see the fish, and they see you,” Hsu says. That sense of untamed wilderness appealed to Knaggs, so Hsu came up with a design that plays off of it in three distinct zones: a stone-walled bedroom area, a wooden garage and gear shed, and the glassed-in living quarters.

Photo: Wynn Myers

The family room.

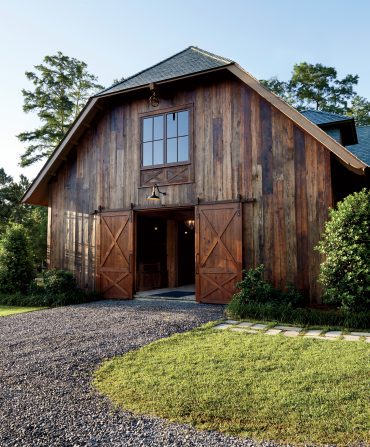

The bedroom wing, walled with irregular limestone blocks in a dry-stack pattern, creates a kind of cocoon. “We sleep better here than we ever do at home,” Barbara says. The limestone, a common building material throughout central Texas, nods to tradition. Similarly, the walls of the large garage and gear shed on the opposite end of the house slide open on both sides, evoking a ranch outbuilding. Hsu sheathed that part of the house in cedar planks that were charred dark brown using a Japanese technique known as shou sugi ban—“a way to finish wood so it holds up but doesn’t look finished,” he says.

Photo: Wynn Myers

Kitchen doors slide open to catch river breezes.

Then there’s the glass box, which encompasses the kitchen and living areas, plus an additional sleeping loft. Walls of glass open at the bottom on the river-facing side and at the top on the opposite side, creating a passive cooling system that draws in breezes off the water. More important, the giant windows eliminate any obstacles from the view. “At night, if the lights are off, it’s like walking into a planetarium,” Knaggs says.

Photo: Wynn Myers

The dining room table, crafted from a solid piece of walnut with a live edge, and chairs upholstered in vintage army-tent canvas dyed indigo.

“One of the reasons we spent those years camping out here,” he adds, “was to show the girls that it’s not just a house in the country; it is the country, and when you come out here, you’re going to get dirty. We wanted the house to continue that sense.” The best tradition yet to develop around that sentiment might be the annual extended-family game of “cowboy soccer” on Thanksgiving—fourteen players joined in last year. Knaggs drove a couple of pairs of metal fence posts into the dirt, down where the ground flattens near the river, and called it a soccer field. “The only rule is that you have to wear cowboy boots,” he says—a protective measure from stepping on cacti but also a way to keep everyone equally off balance and goofy.

Photo: Wynn Myers

Bart and Barbara relaxing by the fire pit.

“A lot of times we come out here and I don’t even go fishing now,” Knaggs says. “Having the house has really changed the way we experience this place.” He stares off down the hill, where the late-afternoon sun plays off the water. “This vista, this house—sometimes you want to just sit right here and watch the river go by.”