The other day I ran into a relatively new friend of mine at one of my favorite New Orleans restaurants, Lilette, and when he introduced me to his tablemates, he told the story of our first meeting. He was clearer than I on the details, which went something like this: We were at the same museum gala, there was good food and good music, and during the course of our conversation I asked if he happened to be in possession of a cigarette. Of course he wasn’t. Most people aren’t these days, and I myself no longer smoke—unless, that is, I’ve been drinking and talking and athletically socializing, and on this particular night I’d been doing plenty of all three. When I asked him if he might find me one, he was dumbfounded. Where, he asked, would he procure such a thing? We were near the stage; the band was between sets. There, I said, pointing straight at the drummer. Now, I didn’t know this drummer from Adam, but my hunch turned out to be spot-on. My gallant new acquaintance returned with a handful of American Spirits, and my benefactor gave me a mock salute.

While this story was being told (to some very nice people, including one guy who happens to be a billionaire), I was standing there, not just a little embarrassed, it having dawned on me that I was not looking all that hot in this narrative. Forward, demanding, trashy even, are just a few of the adjectives that come to mind, but my generous new pal offered up the anecdote as proof of my ingenuity and clairvoyant powers instead. Clearly, he doesn’t know much about drummers.

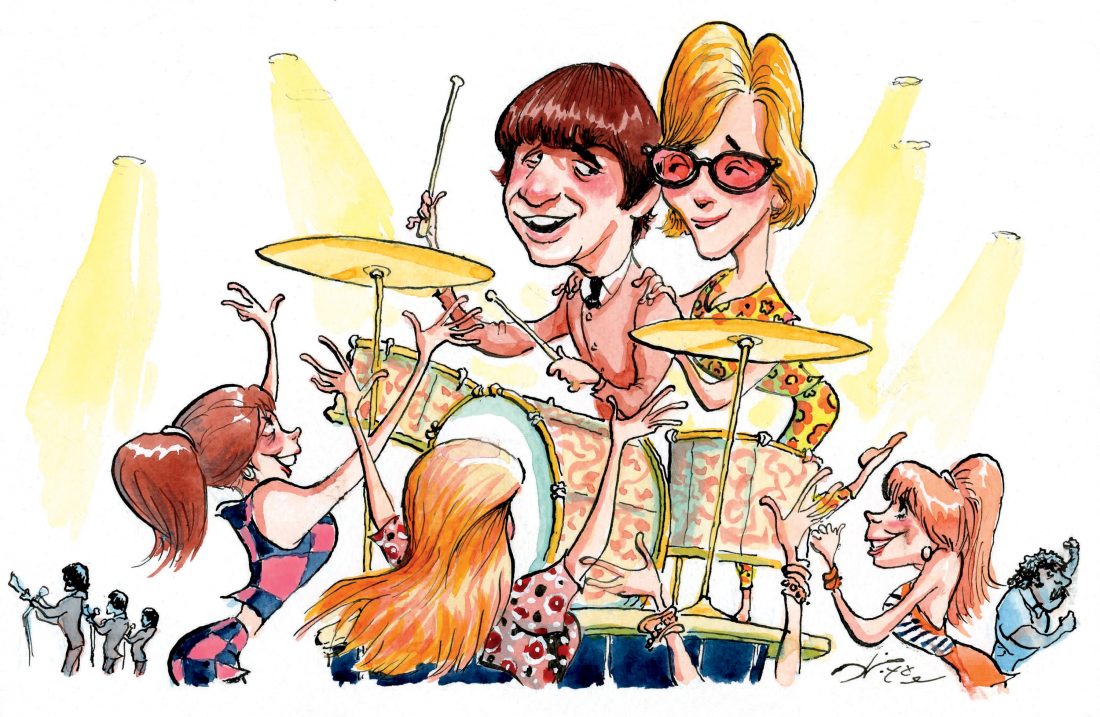

Drummers are badasses. I knew if there were anyone who’d still have a pack or two handy, it would be him (chefs remain reliable sources too, of course, but they were way back in the cooking tent). My great friend Bill Dunlap was a drummer in a rock-and-roll group called the Imperial Show Band before he straightened up and became a painter (and now a writer too) instead. The pantheon of jazz and rock-and-roll greats is crowded: Ginger Baker, Roy Haynes, Philly Joe Jones, Charlie Watts, Buddy Rich, Keith Moon, and Questlove, just to name a handful. If you are too young to know who most of these people are, download their music at once. Without Watts, there would be no Rolling Stones. Ditto Baker and Cream. That sound you hear at the end of the Who’s “Love, Reign o’er Me”? “Moon the Loon” flipping over his drum set. Also, I am not in the least bit ashamed to say that Ringo was always my favorite Beatle, though admittedly my attachment was not immediate. I was three and a half and in Nashville when the band made their Ed Sullivan Show debut. For the life of me, I couldn’t figure out why my entire extended family had gathered breathlessly around my Uncle Evans’s snowy TV set to watch what I had assumed would be insects crawling across the screen. Still, once I got it, Ringo was my man.

One of the more extraordinary facts about my extraordinary mother is that when she was a very chaste sophomore at Vanderbilt, she had a sort of thing with a drummer named, I swear, Otto Bash. A date (a presentable one, a fellow her own age) had taken her to hear Otto at the Celtic Room in Nashville’s notorious nightclub district Printer’s Alley (liquor by the drink, illegal until 1967 in Nashville, was readily available). Fairly quickly, Mama lost interest in the date and took up with Otto, who was almost twice her age. She recalls going to a party at Otto’s apartment where “at least twenty half-nude women” mingled and danced. Inexplicably, she brought Otto home to her parents’ house in Belle Meade, where she still lived, and that was the end of that. When my grandfather, a former naval officer and still very fit star baseball player, discovered them playing cards in the library, he picked Otto up by the scruff of his neck (“sort of like a cat,” my mother says) and escorted him out of the house. “He was a different experience for me, I can tell you.” I’ll say. But I get it. First of all, there’s that name. Second of all, the lure of the minstrel is age-old and powerful.

For example, in the late eighteenth century a Frenchman named Christophe Colomb, who claimed to be a descendant of Christopher Columbus (and who was said to be on the run as a result of a plot involving the French Revolution), turned up on Louisiana’s River Road, home to indigo and sugarcane planters who were then the country’s wealthiest men. One of those planters, Marius Bringier, grew fond of the charming Colomb, an itinerant painter, raconteur, and musician. Not wanting to be deprived of his company, Bringier arranged for his daughter Fanny to marry him, and in 1801 built the couple a stunning Greek Revival box called Bocage that still stands on the banks of the Mississippi. Fanny, all of fourteen at the time, wrote in her diary that she was a tad freaked out about the compelled union, but in no time she too succumbed to the charms of her husband. Fanny ran the plantation while Colomb hung out on his ornamental barge, reclining beneath a hand-painted silk canopy, playing tunes on his guitar. Along the way, the couple managed to have eight children, and by all accounts their marriage was a blissful one.

I was about Fanny’s age when I fell for a similarly captivating minstrel, Leonard Cohen. I wore out the grooves of Cohen’s Songs from a Room on the stereo I took with me to boarding school, and Scotch-taped his dreamy photo (the album sleeve) to the ceiling above my dorm-room bed. The first LP I bought with my own money was Bob Dylan’s Planet Waves, and let me stop and say right here that his Nobel was long overdue. If you don’t believe that lyrics are literature, listen to “Visions of Johanna” or pretty much the entirety of Blood on the Tracks, which is not unlike reading Chekhov. If you don’t believe he’s soulful and sexy as all get-out, even now, listen to Joan Baez singing “Yellow Coat.” Or to Dylan’s own “Something There Is about You” or “Sara” or “Tonight I’ll Be Staying Here with You.” I could go on. Anyway, the best songwriters have always been poets. Cohen’s endlessly romantic “Alexandra Leaving” was based on C. P. Cavafy’s “The God Abandons Antony”—except that, naturally, Alexandria the city becomes Alexandra the woman.

When I was in college, I turned my attention to a musician from my hometown whom I actually knew. As with Otto Bash and my mother, he was at least twice my age, and even though he lived in L.A. and I lived in D.C., we got together whenever we were in the Delta, which was a fair amount. He was heavenly to look at, had a real-live band called Fun with Animals, and when he played the piano was so emotionally and physically all in, it was impossible to take your eyes off him. During one spring break visit home, I had a dinner party at my parents’ house that ended up with everyone taking a dip in the unlit pool, and when we got out, I noticed that the object of my affection was missing—along with my best friend. Almost a whole day later they were found, communing in a cotton field, by the local sheriff, who had been roused by my friend’s increasingly frantic mother and rather more disgusted father. I was a tad miffed myself, but I forgave her pretty quick. I knew, after all. At the time, he’d been testing out a ballad that began, “With Jack Daniel’s for company, you go wherever you please.” The chorus contained the line “But I’ll wrap my love around you, all night long,” and you sort of had to hear it, but, trust me, it was heartbreaking in all the right ways. Plus, the best friend in question (and yes, she still retains the title) happens to be a musician too. In fairly short order, they ended up getting married and stayed that way long enough to have a son, a talented chef and a fine, funny young man who is one of the people I love the most in this world.

When I thank God for their union, I’m not even being magnanimous. But I knew it wouldn’t last—that’s not what these guys are for. Which is not to say they can’t be useful in other ways when it comes to marriage. On the night my parents gave a holiday party to celebrate my engagement to the man who would have been my first husband, an old flame—also a musician and songwriter of prodigious gifts—turned up at midnight, uninvited, at the front door. Without much of a word, he sat down at the piano. My best friend, already single again by then, called down the street for a guitar she knew my neighbor had gotten for Christmas. The would-be groom went to bed, which should have tipped me off right then and there. The rest of us stayed up past dawn singing impromptu songs written, improbably, about the recent fall of the Soviet Union. One began, “Dubček is a redneck”; another, a take on the great blues classic (at least in my hometown) “Greenville’s Smokin’, Leland’s Burnin’ Down,” referenced (rather starkly) Ceausescu’s leg smoking and Bucharest burning down. I’m sorry, but you can’t help but be crazy about someone who is that agile with both his brain and his picking fingers, especially at that hour of the morning. When he launched into one of my favorites, a song he wrote containing the line “You make me nervous when you lay down beside me,” I realized a particular sort of romance had been missing from my life for a little too long.

The good thing is that these days romance is as easy to call up as tapping the iTunes app (which I did, a lot, in November during the days after Leonard Cohen’s death). Also, even though all my boyfriends are dropping like flies (the loss of Cohen, Leon Russell, and Glenn Frey in a single year meant a serious depletion of my life’s sound track singers), those left standing are still, valiantly, hard at it. A few years ago, my parents were in Nashville for an event and my mother got wind of the fact that not only were the Rolling Stones staying in their hotel, they were playing the next night at the Vanderbilt Stadium. Mama bribed the doorman for tickets, and my father, mightily fearful that he would have to attend, decamped. I was happily pressed into duty instead and hopped a plane immediately. It was great: Mick did his indefatigable thing, Keith wore a fetching chiffon leopard print duster, and Charlie was as infallibly cool as ever. Afterward we went to Morton’s, split a big piece of rare meat, and toasted our evening with a nice bottle of red. As it happens, Morton’s is very near the old Printer’s Alley. It was that night that I learned all about Otto Bash.