Artists

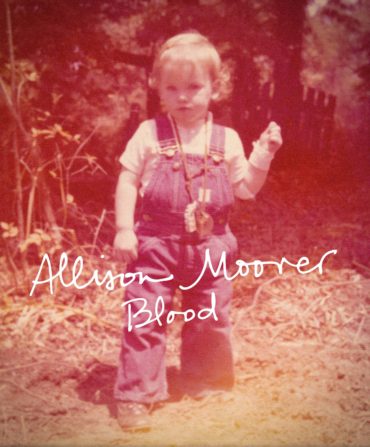

Allison Moorer’s Healing Notes

Bringing a deeply painful past into the light, the singer-songwriter’s new memoir and album are testaments to the power of art—and of the human spirit

Photo: David McClister

Allison Moorer is barefoot on the grass of her Nashville front yard, holding up a water hose and spraying the hell out of a struggling fern. “I am determined to keep this little thing alive,” she announces, her eyes fixed on the trembling plant. Moorer moves with a fierce determination across the yard to hand the hose to her nine-year-old son, John Henry, who is delighted to take over. She is that rare kind of person who always seems as if she has somewhere important to go but somehow still manages to appear unhurried.

The first thing one recognizes about her is her keen intelligence. She is a contradiction—memorably polite but never willing to be a pushover, simultaneously elegant and down-home, a quiet observer who also throws her head back with a wonderfully deep laugh. In the space of a few minutes, she can expound on the writings of Thomas Merton and Pema Chödrön, the struggle to raise a perfect tomato, a recent documentary about Molly Ivins, why the rhythm found in sewing calms her, and the mystery of faith: “God is in rosemary,” she says, reaching down to slide the fragrant plant between two fingers. “I mean, look at it.”

The singer-songwriter, who turned forty-seven last summer, is so lithe and luminous in her navy-blue sundress that it is easy to picture her as a fourteen-year-old girl back in southern Alabama, on an August morning when her life changed forever. After years of his rage and jealousy, Moorer’s mother had left her father. He arrived in the middle of the night to beg her back, but just before daylight, when he saw his pleading wasn’t going to work this time, he shot and killed her and then turned the gun on himself in the front yard of the home where Moorer and her older sister slept inside.

That moment is at the heart of her harrowing new memoir, Blood, and an accompanying ten-song album of the same name. In both she refuses to look away from the tragedy—in one particularly haunting section of the book, Moorer examines her parents’ graphic autopsy records for the first time with a perfect balance of calm description and aching emotion—but never becomes maudlin or self-indulgent. Instead, the one-two punch of memoir and album emerges as a precise, lyrical, and even wise meditation on grief, survival, and the healing power of creating art.

Both Moorer and her sister, the Grammy-winning Shelby Lynne, went on to successful careers in the music business, a fulfillment of the dreams of their parents, who shared a deep love for music. Their mother’s natural-born singing ability often fueled their father’s fury, as he didn’t possess the same talent, despite a tremendous desire to be a singer-songwriter. Less than a dozen years after her parents’ deaths, Moorer had a record contract in Nashville with MCA and soon became an Academy Award nominee after Robert Redford featured the song “A Soft Place to Fall,” a track from her first album, in his 1998 hit film The Horse Whisperer. She appeared in the movie and sang at the Oscars, and over the course of ten albums, she would be nominated for a Grammy and an Academy of Country Music Award and garner many other honors, eventually becoming one of the best-known and most beloved figures in the flourishing Americana music scene.

Moorer believes she would have been an artist regardless of what happened to her parents, but a very different one. “I don’t think my art would have had as many teeth as it does,” she says. “I don’t think you have to necessarily suffer to make great art, but the truth is that most great art is born of it.”

Photo: David McClister

Allison Moorer with her dog, Willie, at her home in Nashville.

Before her parents’ deaths, Moorer tended to observe quietly while her family boiled around her. “I was the family memory,” she says. “From a tiny age, I spent a lot of time by myself, reading books or listening to records. I’d watch them fighting and think, ‘There’s something wrong with y’all, and it’s not me.’” Her sister, who is three and a half years older, took the opposite approach, which on at least one occasion led to their father badly beating her. “She was so worried about Mama that she really thought she needed to be around to protect her, to distract Daddy,” Moorer remembers. “When he’d get mad at Mama, Shelby would always do something to say, ‘Oh, look over here.’” Moorer still blames herself for not intervening, even though she was a child at the time. “I carry a lot of guilt about [Shelby], knowing I didn’t do anything. I was useless.” She goes quiet a moment, her ghost-blue eyes dampening. “That was the hardest part. Knowing that she was hurting. I’d think: ‘I’m fine, and those two are adults. But her.’” She shakes her head, remembering, then lets out a breath so long and weary she seems to have been holding it for years.

The sisters today share a profound, unbreakable bond. They call each other “Sissy,” and Lynne wrote the foreword for the book, which she says changed her life. “Her voice has allowed me to open my own buried pain,” Lynne writes. In 2017 they released an acclaimed album together containing nine perfectly chosen covers and one original, “Is It Too Much,” which takes a simultaneously tender and gritty look at the trauma of their parents’ deaths and the way they have leaned on each other to survive. The album led to a string of raw and moving performances that have become legendary among those who witnessed the shows. “No one else walks upon this road,” they sing to one another in the song. “No one else bears this heavy load.”

A couple of weeks later, Moorer is at AmericanaFest in Nashville for a series of events, including a performance at the venerable War Memorial Auditorium, a quickly sold-out gig at the famous Bluebird Cafe, and a surprise appearance at the showcase of her husband, the Texas-born singer-songwriter Hayes Carll, whom she married this past May.

At each event, audiences seem mesmerized by the new material. Her voice is a powerful entity that prowls a room, raising goose bumps on the backs of arms. Yet it is more than just masterful singing. Whether she is performing a rollicking foot stomper or a plaintive ballad, there is always longing in her voice. Combined with her constant themes of history, love, and conflict, it makes for something primal. At each performance, someone is wiping away tears. In song after song, in some iteration she is often singing about family (her parents, her sister, her son, her loves), which may be the most primal thing of all. People are moved because they all understand the kudzu-vine complications of family. They’re moved because Moorer can so potently articulate that there is power in the blood.

David McClister

Moorer and her sister have been sharing snippets of their lives their entire careers, but while most press has mentioned the way their parents died, very little has been written about the way they lived. While Moorer doesn’t shy away from the hard parts—revealing much more about their story than ever before—she wants people to know that her childhood wasn’t all trauma. “In some ways, it was idyllic,” she says in the cramped greenroom of the Basement East (“the Beast,” in local parlance), a venue in East Nashville where Carll has just gone out to entertain a raucous crowd of fans. She’s sipping a vodka and soda and leaning in close to talk over the music. “My parents were alive. They were wonderful and complicated and creative. We were always fishing and singing together and roaming the countryside.”

Making art was a daily occurrence at their house, and Moorer is grateful to them for instilling in her a drive to create. Her parents were constantly in motion: sewing, building furniture, and always singing and writing songs. Before long she saw that making art could be a mode of survival, a way to disappear into words and music. She wrote her first song at age eight—about Australia, where a classmate had lived—and she can still sing it: “Australia is a funny place to be / with kangaroos, koalas, and the sea.” But even as a child the existential-questioning artist was already there: “I have never been to Australia and I bet I never will be / ’Cause I’m right here and I always will be.” She’s hardly stopped writing since, and she continues the family tradition of persistent creation not only with her songs, but also by tending to the petunias she raises in memory of her mother, or sewing a pair of curtains.

“To see an artist in her full glory renders the world bearable,” Moorer writes in the memoir. Then, a little later: “Putting a creation into the world is asking to be understood and loved. The answer is not always yes.” What Moorer has come to realize is that the reward has to lie in the work itself. “Sometimes people just don’t respond,” she says. “But I was in my forties before I understood that the doing is what matters. What we leave behind is important.”

After John Henry was born, she began to think even more about legacy. Her son was diagnosed with severe autism, and she thought she might never be able to go out on the road again as a musician. So she signed up for graduate school and earned a master of fine arts in creative writing. “I knew I had to do something,” she says. “I knew I’d have a terminal degree that I could use. That’s the practical side I got from my mama.” She also wanted to hone the craft of prose writing.

“Some days I would sit at my desk and just brace myself, just hold on,” she says of working on the memoir. “It’s too big and painful, to take yourself back in an active way. Actually calling it back.”

The greatest accomplishment of the book may be that it allows her parents to live again, giving their stories the light of day. Her mother in particular comes to life with great specificity. Moorer recounts every detail she can remember—her hands, her smell (“like laundry dried on the line with an added bit of spice”), the way she always carried Doublemint gum in her purse—and conjures the picture of a fierce, frightened, and incredibly hardworking woman. “I realize now what a gift she gave me by showing up. I don’t know how she did it. Somehow I got out of there feeling loved by her, and she just did that by force of will. Because she was distracted, and she had a needy husband who wanted all of her attention.”

Moorer says she sometimes pictures her mother walking into her home in Nashville and looking around. “I can imagine what she’d say. I can smell how she smelled,” she says, more quietly now. “It’s such an absence. No one else can fill that hole. Not having her little special touches has been one of the hardest things in my life. Not having her to be my mama.” Then, as often happens with Moorer, grace interrupts and she unnecessarily chides herself. “Now, that’s selfish of me. Not having her in the world is a huge absence. She was a light.”

She often thinks about what life could have been like if her father had gotten the help he needed and says that she sometimes finds Alabama state quarters that she believes he leaves for her. She also feels that her mother is frequently playing with her son. “Grief never goes away,” she says. “It might change shape, but it always has its teeth in you. Trauma you can actually heal from. Writing this book and making this record have gotten me closer to that than I’ve ever been. You’ve gotta get it out of you. You’ve got to tell your story.”

Moorer also found that writing the book and being a parent have summoned more empathy, a theme constantly under examination in the memoir and the new music. On the album she showcases songs from each of her parents’ points of view and even records a song her father wrote a few years before she was born, which includes eerily prophetic lyrics: “I’m the one to blame, but I’ve paid the cost / Time has made me see just how much I lost.”

At her house, Moorer is seated at her kitchen nook with her small one-eyed dog, Willie, curled up as close as he can get. Behind her the entire wall is covered with a couple dozen family photographs—some current, others from the far past—all outfitted in sleek black frames that make them part of one large installation. Portraits of her son and her mother reveal a startling resemblance. In another picture her father is smiling down at her. “I cannot think about my daddy without feeling sorrow for him, for how miserable and lost he was,” she says. “And that’s just the power of love.” She points to the kitchen ceiling, which is painted a rich turquoise. “I painted the ceilings blue to keep the ghosts out,” she says, referring to the long-standing Southern tradition. “Obviously it didn’t work.”

Moorer has only recently moved back to the South, relocating to Nashville last spring after fourteen years in New York City (much of that time with her ex-husband, the musician Steve Earle). “I missed people making deviled eggs and pimento cheese,” she says. “I missed the warmth of folks. I needed to come home. I don’t really like New York City all that much as a place to live. There aren’t any porches there. Not a whole lot of ‘Hey, I cooked a pot of beans, you wanna come over?’”

She says she feels like she’s on the verge of a second act, a new chapter. Art has always been her way of preserving, of keeping the stories alive. Outside, she pauses at the foot of the porch step, smiling as she watches her son play in a large mudhole he has fashioned with the hose. “I’m so well loved by a whole lot of people who want me to do well,” she says after a moment. “There is no better place to be than that.”

Behind her, the little fern she had soaked before is dripping, its small hanging basket turning back and forth as it struggles with the saturated weight of its soil. Already its leaves seem greener, glistening with water, pressing on for a little while longer.