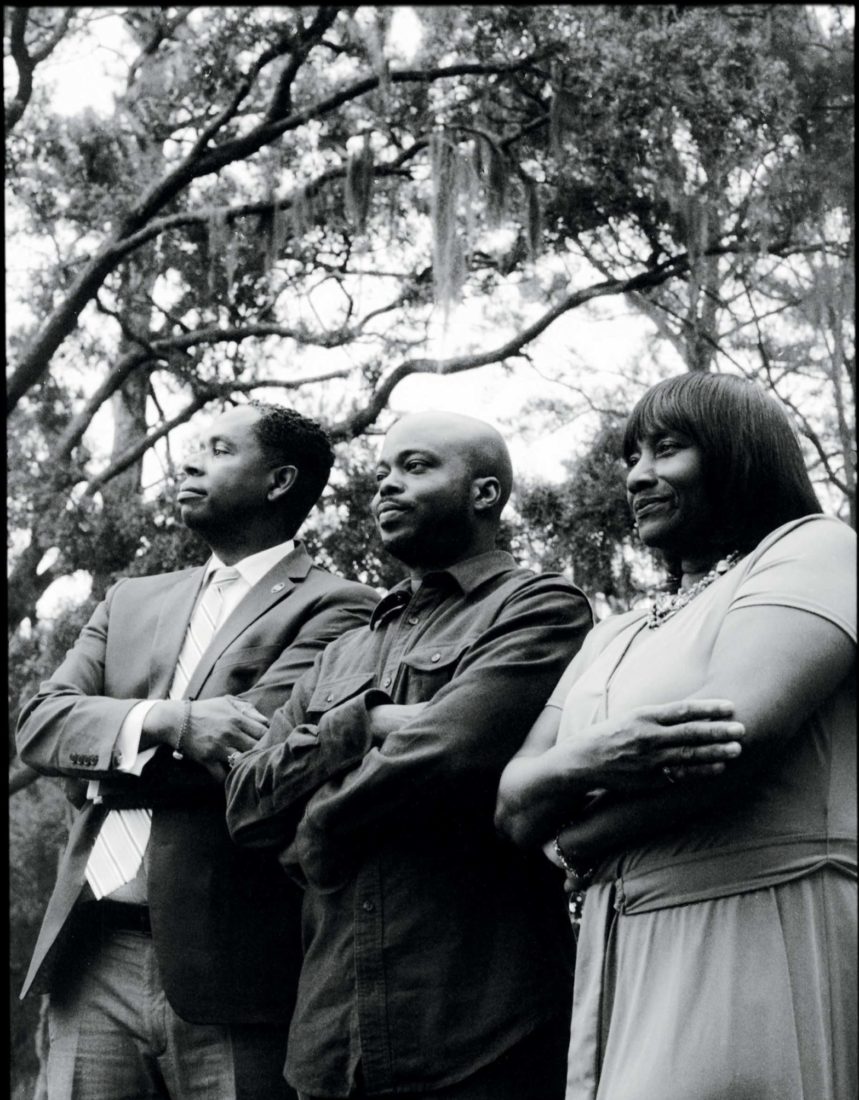

SOUTHERN HEROES

Amir Touré, BJ Dennis, and Sallie Ann Robinson: The Torchbearers

Three guardians of Gullah Geechee culture work to help their Lowcountry traditions not only survive, but thrive

Photo: Gately Williams

The Gullah Geechee culture, long vulnerable to time and tide, has found many champions, including Benjamin “BJ” Dennis IV, Sallie Ann Robinson, and Amir Jamal Touré. Each of these experts descended from formerly enslaved Africans who lived on islands along the Southeastern coast. Isolated from the mainland, these communities kept many African traditions and language markers, and the dialects that emerged became known as Gullah, or Geechee, depending on the locale. But the term Gullah Geechee encompasses more than a way of talking—to the descendants, being Gullah Geechee is a way of life.

Dennis, a Charleston-born chef, has earned praise for his ability to fuse the flavors of the Lowcountry with the foodways of his Gullah Geechee roots, expressing the journey of the people of the African diaspora through food. Robinson, a sixth-generation resident of Daufuskie Island, South Carolina, has become known for her love of storytelling and cooking the traditional food of her youth, both of which she shares in her three cookbooks, including her latest, Sallie Ann Robinson’s Kitchen: Food and Family Lore from the Lowcountry. Touré is a cultural historian and Savannah State University professor whose family has been in the Georgia and South Carolina Lowcountry since at least 1814, a history that informs his Day Clean Journeys, a tour company named after the Gullah term for “a new day” that he founded and that focuses on Gullah Geechee sites of importance.

Recently in Beaufort, South Carolina, the trio convened to discuss their shared history and the endangered traditions of the Gullah Geechee people.

How do you describe yourselves: Gullah, Geechee, or Gullah Geechee?

Robinson: Folks want to separate us, to try to define who you are by where you’re from, but we from all over. People try to get me to define what Gullah is. I say, “Well, there’s many definitions.” I grew up not even knowing the word Gullah. The tourists came in the early seventies. A lady told me, “Ah, we come in to look for the Gullah people.” I said, “Who dat be?” I had no clue that it was my culture. I was like, Are they calling us something we don’t know about? Are they trying to name us something that we not aware of? Because we didn’t have libraries [on Daufuskie]. We didn’t even have electricity or the telephone over there until the seventies.

Touré: I say that I’m Gullah Geechee. I grew up in Savannah, but also in Hilton Head. So that’s why I say I’m from both sides of the water. Savannah is unique in the sense that when you talk about Savannah, Savannah has always been tied to Daufuskie, Hilton Head, Bluffton. So we can’t isolate.

Photo: Gately Williams

Amir Touré.

Language has been an important marker of the culture, but the way you talk hasn’t always been embraced.

Robinson: It was the early seventies when I went to Savannah. These kids had no knowledge of the culture, and they were like, “You don’t speak like we do. Get from here.” I got teased. I cried. I had to fight, and it really made me want to shut myself down. All I wanted to do was fit in. It was tough, but then I learned to learn more about it, so that I could be more comfortable with who I am and my culture. That’s why I do all my research and studies, because I don’t want my children and the next generation to have to deal with that. I have fourteen grandchildren, and I intend to leave a legacy of knowledge and evidence for them.

Dennis: I was told that in olden days, when there were no bridges, every island accent had a little difference. I talk with a slippery tongue. It’s a fast talk. My tongue—I can roll my words, but that’s just the beauty of the culture. The language—the core of it, the words that we speak—is the same, but the linguistics can be a little different from each area. My grandmother is from off the island, so when she speaks to me, that’s the old Gullah. It’s deep and singsong. She’s singing to me when she talks.

Touré: In Savannah, Hilton Head, and Dau-fuskie, we say “churn” [instead of “children”]. Now, on the Riceboro side, they’re going to say “chillun.” In Charleston they might say “chillum” or “chil’ren.” That’s the nuance for each of our areas.

When did you understand that the way you were raised was unique?

Dennis: For me, growing up in Charleston, we do what we do. We talk how we talk, and you knew you were a Geechee. My parents’ generation, that was a fight to say you was Gullah or Geechee. That was a diss for a lot of people. But my granddaddy was proud to say it. They called him Benny the Geechee. He was proud of that, but a lot of us weren’t, because we thought it was a negative connotation. When I started cooking, I picked up a Charleston cookbook called Charleston Receipts, the oldest Junior League cookbook [still in print] in America, and every chapter started off in Gullah. That’s when things started to sink in for me—I was probably about nineteen.

When I lived in St. Thomas [in the U.S. Virgin Islands], they’d say, “Oh, you one of them Gullah.” And then, “Oh, you’re related to us.” I’d have guys sit with me, telling me about my own people. By then I had Sallie Ann’s cookbook, I think. My history was always there, but it took leaving to be like, “Oh, wait a minute, there’s something special.”

Photo: Gately Williams

BJ Dennis.

Living close to the land and the resulting foodways are such a large part of the Gullah Geechee story.

Dennis: One of the [ceremonial] kings from the Dahomey kingdom [in present-day Benin] was here in Charleston a couple of months back. I took him some food. He was blown away. He was like, “This reminds me of the food from my home.” I said, “Because it is. We are the extension of y’all. We are the ones who survived.”

Robinson: My love for food comes from the way I grew up, the dishes I learned to cook and how I learned to cook them. When I was writing my first book, I told a friend. He said, “Gal, ain’t nobody going to buy no book with no coon, possum, and squirrel in it,” and the group that was around started laughing. The book did well. My frustration comes from people taking our dishes and the techniques our ancestors taught us and naming the food something else, claiming it for themselves.

What else frustrates you about how Gullah Geechee culture is depicted today?

Touré: You get inaccuracies when we’re forced to rely on somebody else to tell us our story. Most people want American mythology, not American history. The nice sanitized Negroes, the happy-go-lucky Negroes. No—you have people who are powerful and created this landscape. Rice fields didn’t just appear. Appropriation is a big one right now. I tell folks that “eco-living” has always been our way.

Robinson: I tell people that all the time. We ate better than most people, because we ate organic. We were organic before they even knew the word organic. People take our food and turn it into their delicacy.

Touré: It’s being rebranded by tourism, and different ventures are getting grants, offering us pennies to perform for tourists. We’re trying to shut that down and be in control of our own story. People like [the famed root doctor] Dr. Buzzard have been exploited. That’s the issue I’ve got, the pimping of our culture. Dr. Buzzard is not just a character. I do [research for] Dr. Buzzard’s great-grandchildren. This is a family.

What do you believe to be the biggest threat to the Gullah Geechee community?

Dennis: The education of our people, understanding who they are, is missing. When I’m at James Island High School on James Island [South Carolina], and sitting there talking about the culture, I’m like, “Who in here know they’re Gullah Geechee?” The black kids are staring at me. The self-hatred that we’ve been through to try to fit in—that’s the part that’s the issue for me. It’s not the culture that is vanishing. It’s teaching about our culture, and our history, and our roots. Who knew the waterways? Now I know children who have never been to the beach, and the beach is down the street.

Robinson: We are not sitting our children down and talking to them, teaching them not only their culture, but their food. I went to the Hilton Head Island School for the Creative Arts. I was talking about food. I said, “When I was growing up, none of these stores and shopping mall was here.” They were like, “Well, how did y’all do?” And I say, “Well, honey, we had the ocean, the woods, and the garden.” They’re like, “Huh?” I spoke about okra. They said, “Oh, we love okra.” It was forty-five kids. I had a jar of pickled okra, with whole okra in it. I asked, “Can anybody tell me what this is?” Not one of them kids could tell me what an okra looked like, not one. They’ve always seen it chopped up and breaded. That’s how our culture is losing our children. I realize that once we’re gone, this era right now, if this era doesn’t make an impact on our children, then we are going to lose a whole lot. We’re going to lose way more than what we already lost.

Photo: Gately Williams

Sallie Ann Robinson.

What makes you persevere? What gives you hope?

Dennis: For me, the hope comes when I can connect. We went to Sierra Leone, and a video came out where they were doing the sweetgrass baskets [like the ones made by Gullah Geechee weavers in Charleston], and both cultures were blown away. If it takes me going into the schools, okay. I was a culinary mentor for a program at Burke High School, and the boys, when they see me now in the streets, they want to give me hugs. I’m there just to give them that encouragement.

Touré: In Gullah, when we say “we,” that means us—but it can be single and plural. It gives you a sense that it’s never just about you. There’s going to be generations after me that will see that we were a part of this preservation effort that we’ve created for our ancestors, because they survived. What we are doing now is just being a part of that process, so for me it’s always excitement. There’s always hope.